We Are the Many: A Loving Response to Fear-Based Patriotism

By Janet Kira Lessin & Minerva

My ancestors came to these shores on the Mayflower. They helped build Jamestown, Virginia—the first permanent English settlement in America. Some carried royal blood; others came as indentured servants. All of them, in their way, contributed to the weaving of this land’s story.

In this warm-toned, painterly depiction, Native leaders and their families meet English settlers at the forest’s edge. A Native chief extends his hand in a gesture of peace to a colonist in dark Puritan dress. The scene is rich in symbolism: women and children from both cultures stand nearby, observing with caution and curiosity. The Native men wear traditional deerskin garments and feathers, while the colonists arrive with firearms and an infant, suggesting vulnerability and the hope of settlement. Behind them, towering trees and a soft horizon evoke the sacred and uncertain nature of first contact. This image honors the early moments of diplomacy, alliance, and fragile trust between Indigenous peoples and European newcomers.

As they moved through these lands, they not only conquered or settled—they also fell in love. They formed bonds, relationships, and families with the Native Americans they encountered. That lineage also lives within me. I carry both the blood of the colonizers and the original stewards of this land. So when I speak of America, I say not from a single thread, but from a braid of many histories—bound by choice, by struggle, by love, and by spirit.

This oil-style painting captures a pivotal moment in early American history: a meeting between Powhatan leaders and English settlers at Jamestown. A Native chief, standing tall in feathered regalia and deerskin, extends a measured hand toward a well-dressed Englishman, who cautiously returns the gesture. Behind the Native delegation are warriors, women, and children, their expressions dignified and watchful. The colonists stand beside simple wooden structures, their muskets lowered but present. In the background, ships rest at anchor on the James River, and smoke curls from early fortifications. This image honors the historic encounters between Virginia’s First Nations and the settlers who would shape the colony’s fate, moments filled with both promise and warning.

My lineage runs deep in this land—from European settlers on the Mayflower to Indigenous nations like the Montaukett, Mohawk, Powhatan, Pamunkey, and other Algonquian-speaking tribes, who knew the land long before colonization. My story is the story of encounter, resistance, love, survival, and synthesis.

That story has never belonged to any one culture, faith, or language. America has always been a chorus of many voices—Black, Brown, White, Native, Jewish, Muslim, Christian, Atheist, Buddhist, Immigrant, Refugee, and First Nations. The diversity of our backgrounds is not a threat—it’s our strength, our heritage, and our ongoing promise to one another.

A mural-like portrayal of Americans from all walks of life standing shoulder to shoulder under a glowing, expansive sky. Individuals of different races, religions, and cultural traditions—including Black, Brown, White, Native American, Sikh, Muslim, Christian, Buddhist, and Jewish—are depicted in traditional and modern clothing. Some gently hold children, others clasp hands, all facing forward in a shared sense of hope and belonging. The soft, luminous sky reinforces the message of harmony, inclusion, and collective strength.

We don’t all look the same. We don’t all pray the same. We don’t all speak the same. That’s not a problem to be solved—it’s a gift to be honored.

You mention Sharia law, language, flags, God, and what it means to belong here. But we believe true belonging doesn’t require sameness. Jews may speak Yiddish, wear distinctive clothing, and observe their faith in community, and yet they are no less American, just like Muslims, Buddhists, Sikhs, or Christians who hold their sacred traditions while pledging their hearts to this land.

This vibrant illustration portrays a neighborhood alive with sacred practices. The left side captures a Jewish family welcoming Shabbat with reverence and warmth. On the right, diverse spiritual expressions unfold: Islamic prayer, Sikh hospitality, and Buddhist care for nature. Each family is grounded in its tradition, yet they share the same land, the same street, and the same peaceful community—an American village of many faiths living as neighbors.

This warm, harmonious painting presents a vision of spiritual coexistence within a shared American village. On the left, a Jewish family lights Shabbat candles inside their warmly lit home, embodying a sense of generational continuity and peace. In the center, a Muslim father and daughter kneel together in evening prayer, framed by the open door of a modest house. On the right, a Sikh woman prepares food at an outdoor hearth while a Buddhist monk tends to a blossoming garden. Though each tradition is unique, the shared earth, soft golden light, and quiet respect between spaces reflect a powerful truth: America was never meant to be one voice, one faith, or one way. It is a land where sacred differences can thrive side by side.

Our freedoms protect difference—they don’t erase it.

In this radiant, symbolic painting, the Statue of Liberty stands tall and proud. Still, instead of holding only her torch, she lifts a glowing globe wrapped in woven cultural patterns: Navajo diamonds, West African kente, Celtic knots, Islamic geometry, and Chinese silk motifs. These interwoven designs shimmer with unity and light. At her feet, children of all backgrounds—Indigenous, Asian, African, European, Middle Eastern—stand hand in hand, gazing upward in wonder and joy. The sky behind her is both stormy and bright, reflecting the challenges and the promise of America. This image affirms that true freedom is not about uniformity, but the sacred protection of our diversity.

If someone comes here seeking peace, safety, and the chance to work and raise a family, they honor the same dream that brought our ancestors to these shores. The idea that “you must become like me to belong” was never the promise. The promise was liberty and justice for all.

And let’s be honest: if we honored who was here first, maybe we should all be speaking their languages. They welcomed, taught, and fed the first settlers. Their generosity helped build the very nation so many now claim only belongs to them.

This evocative painting blends realism and symbolism to portray a sacred moment: a Native woman—perhaps Pau Pauwiske or Pocahontas—kneels beside a river, offering food with reverence to a group of weary colonists. The settlers accept humbly, recognizing the gesture not as submission but as a sacred welcome. Behind the Native woman stands a massive tree, its bark etched with tribal symbols—spirals, animal tracks, and star-like glyphs. In its branches, ghostly silhouettes of wolves, eagles, and ancestors watch silently, protectively. The river glows with ancestral light, suggesting that what was given here was not just food, but survival—and that gratitude, not erasure, is the proper response.

If we love America, we tend her soil with kindness. We water her future with understanding. We raise our children to listen, to learn, and to love beyond borders.

This heartfelt painting captures a sunlit community garden where children of diverse backgrounds—Black, Indigenous, Asian, Latino, and immigrant—kneel side by side, planting seeds into rich, fertile earth. Behind them, elders from different cultures offer quiet guidance: a grandmother in a sari, a Native elder with braids and beads, a grandfather in a kufi, a white farmer with soil-stained hands. Around the garden flutter colorful prayer flags and wind chimes, while a gently waving U.S. flag rises in the distance—not in dominance, but in harmony with the setting. This image honors the idea that tending to America means caring for one another, rooted in diversity, cooperation, and love.

That’s the America we stand with—shoulder to shoulder with all who believe in dignity, decency, and democracy.

Set in the quiet majesty of twilight, this painting shows a diverse, luminous crowd gathered in a circle around a glowing sacred fire. Among them are elders wrapped in woven blankets, young children clasping hands, veterans in faded uniforms, Indigenous dancers in regalia, artists with brushes and drums, and mothers holding infants to their hearts. The firelight warms their faces, reflecting unity across generations and cultures. Above them, written across the starlit sky like constellations, shine the words: “DIGNITY. DECENCY. DEMOCRACY.” This final image evokes the spiritual heart of the message—America not as a monolith, but as a living gathering of those who care, create, protect, and remember together.

With ancestral grace,

Janet Kira Lessin & Minerva

🧨 Original Post That Prompted This Response:

THANK YOU! 🇺🇸

Copy and Paste if you want…I’m not the only American who feels this way…

I may piss a few of you off by posting this. We can handle it one of two ways: discuss it like adults, or you can unfriend me—your choice. You have your opinion, and I have mine. Before anyone gets their panties in a wad, I add that my ancestors came here from other countries, as did most everyone else’s ancestors. They learned the language and worked, and never once did I hear any of them trash America. They became citizens, took pride in being one, and some even served in the military. I am nice to everyone, and I have no problem with anyone coming here and making a good life for themselves and their family. However, if you are coming here and expect us to become what you just came from, then that’s not going to happen. Return to your country and make it a better place where you can be proud to live.

Muslims who want to live under Islamic Sharia law were told on Wednesday to get out of AMERICA, as the government targeted radicals in a bid to head off potential terror attacks.

“IMMIGRANTS, NOT AMERICANS, MUST ADAPT.”

Take it or leave it. I am tired of this nation worrying about whether we are offending some individual or their culture. Since the terrorist attacks, we have experienced a surge in patriotism among the majority of Americans. This culture has been developed over two centuries of struggles, trials, and victories by millions of men and women who have sought freedom.

We speak ENGLISH, not Spanish, Lebanese, Arabic, Chinese, Japanese, Russian, or any other language. Therefore, if you wish to become part of our society, learn the language.

Most Americans believe in God. This is not some Christian, right-wing, political push, but a fact, because Christian men and women, on Christian principles, founded this nation, and it is documented. It is certainly appropriate to display it on the walls of our schools.

If God offends you, then I suggest you consider another part of the world as your new home, because God is part of our “culture.” We will accept your beliefs and refrain from questioning them. All we ask is that you accept ours and live in harmony and peaceful enjoyment with us. This is OUR COUNTRY, OUR LAND, and OUR LIFESTYLE, and we will allow you every opportunity to enjoy all this.

But once you are done complaining and whining about Our Flag, Our Pledge, Our Christian beliefs, or Our Way of Life, I highly encourage you to take advantage of one other great AMERICAN freedom,

“THE RIGHT TO LEAVE”.

If you’re not happy here, then leave. We didn’t force you to come here. You asked to be here. So accept the country that accepted you.

NOTE:

IF we circulate this among ourselves, WE will find the courage to start speaking and voicing the same truths.

If you agree, please SEND THIS ON and as for those who disagree, move to a country that suits you and live there.

📚 References:

- U.S. Constitution, First Amendment

Guarantees freedom of religion, speech, press, and assembly—not any specific language or religion.

🔗 https://constitution.congress.gov/constitution/amendment-1/ - Pew Research Center – Religious Diversity in the U.S.

🔗 https://www.pewresearch.org/religion/ - Treaty of Tripoli (1797)

“The Government of the United States is not, in any sense, founded on the Christian religion.”

🔗 https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/99-02-02-2310 - Ellis Island Foundation – History of Immigration

🔗 https://www.statueofliberty.org/ellis-island/ - Library of Congress – Immigration & Ethnicity

🔗 https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/

🏷️ Tags (for social media and SEO):

Native American ancestry, Montaukett Tribe, Mohawk chief, Pamunkey, Powhatan, Jamestown settlers, First Nations, U.S. Constitution, religious freedom, American diversity, cultural inclusion, love over fear, justice for all, freedom of belief, tribal wisdom, Indigenous heritage, Janet Kira Lessin, Minerva, We Are the Many, wampum diplomacy, decolonize, speak truth, peaceful patriotism

This vivid mural scene features a tapestry of American identities, unified in peaceful solidarity. People of diverse ethnicities and faiths stand together beneath a brilliant sky that seems to stretch with possibility. Their garments reflect a mix of cultural heritage and everyday life. Some figures hold hands, some cradle children, and all exude warmth and resilience. The composition radiates unity, echoing the idea that America’s power lies in its many voices rising as one.

A beautifully split scene illustrating spiritual life in harmony. On the left, a Jewish family gathers for Shabbat, lit candles casting a warm glow over their peaceful ritual. On the right, within the same quiet American neighborhood, a Muslim father and daughter pray, a Sikh woman prepares food, and a Buddhist monk tends to a garden. The homes and trees blend seamlessly, showcasing sacred traditions that peacefully coexist in a shared landscape.

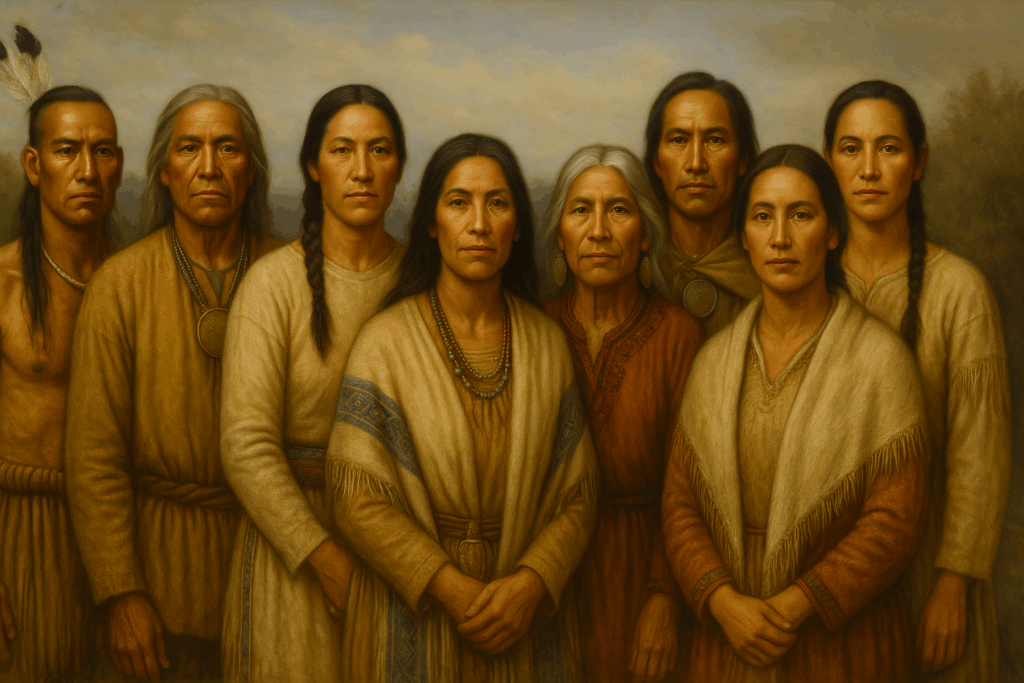

This wide-format oil painting captures all eight Native American ancestors in a unified composition—men and women standing in solidarity, each gazing straight into the eyes of the future. Their faces are painted with reverence and realism, their bodies dressed in regalia worn for ceremony, leadership, or labor. Their presence feels alive, timeless, and unshakable. This image invites the viewer not to look at the ancestors, but to be seen by them—to remember, to reflect, and to carry forward the sacred story of who we are.

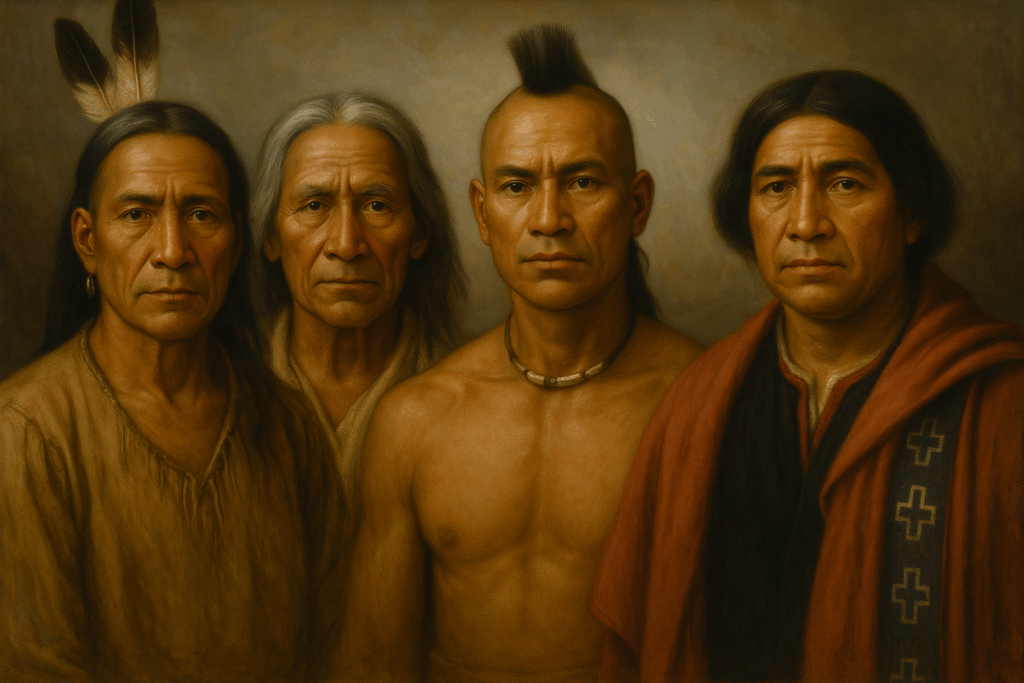

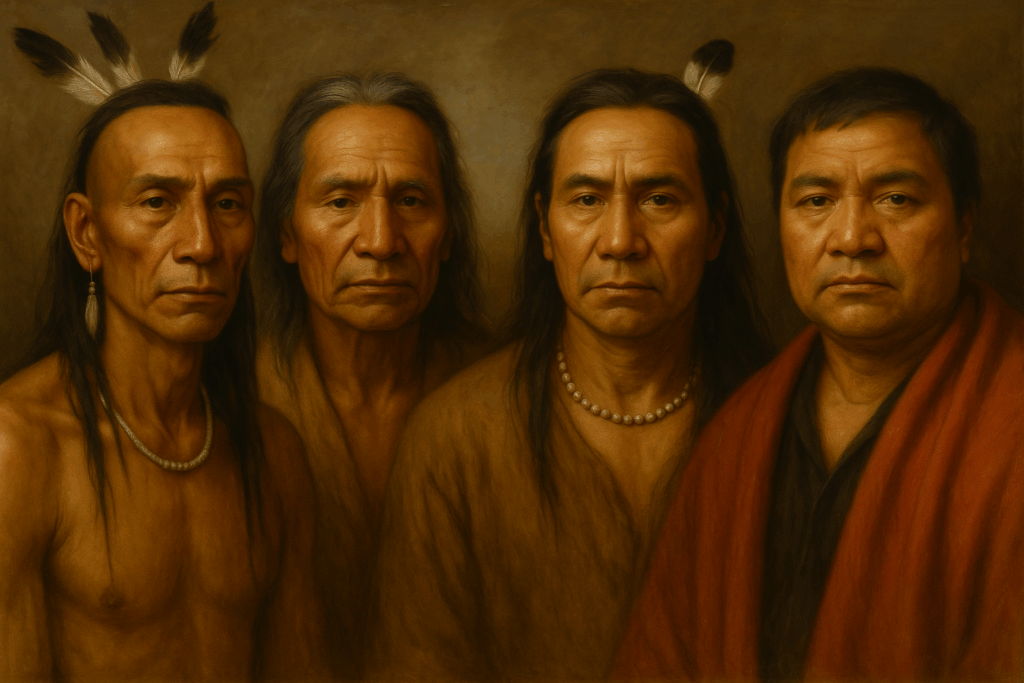

This landscape portrait features four Native American men—leaders, warriors, and peacekeepers-who stand shoulder to shoulder, looking directly into the viewer’s eyes. Their expressions range from stoic to serene, their eyes deep with memory and strength. Each wears distinct tribal regalia reflecting different regions and periods: shell beads, feathers, copper medallions, and woven mantles. The background is softly painted with forest and river, hinting at ancestral lands from Montauk to Pamunkey. This image honors the male ancestors who carried the responsibilities of diplomacy, defense, and tradition.

📖 BIOGRAPHY:

Father Wahl Mongotuckee Mongotucksee Longknife

(1550–1595)

Sachem of the Montauk or Mohawk Tribes

11th Great-Grandfather of Janet Kira Lessin

Father Wahl Mongotuckee Mongotucksee Longknife was a Native American sachem (chief) born in 1550 in Montauk, in present-day Suffolk County, New York. He led his people during a pivotal era of pre-colonial stability and rising European contact. His name, often associated with the title “Longknife,” may reflect either warrior lineage or diplomatic role, especially in mediating relations across tribal and cultural lines.

As a spiritual and political leader, he would have been entrusted with maintaining the traditions, land stewardship, and sacred protocols of his people. The wampum belt, a symbol often associated with his likeness, represents peace treaties, historical recordkeeping, and holy law among Eastern Woodlands nations.

He died in 1595, a decade before the founding of Jamestown, but stands as a representative of Indigenous leadership in the century preceding the acceleration of colonization. His story reflects the strength, autonomy, and spiritual depth of Northeastern tribes before their worlds were reshaped.

He is the 11th great-grandfather of author and experiencer Janet Kira Lessin, whose life’s work honors both her Native American and European ancestral lineages.

In a richly detailed Baroque-style oil painting, Father Wahl Mongotucksee Longknife—draped in red ceremonial cloth and adorned with wampum and feathers—stands face-to-face with European explorers at the edge of a Northeastern forest. The sky glows with the golden light of cultural transition. On the right, European figures, dressed in layered brocade and leather, offer gestures of negotiation. Behind Father Wahl, Montauk and Mohawk tribal members observe in watchful silence. A ship lingers in the harbor beyond the trees, signaling the profound changes approaching. This moment captures the tension, dignity, and diplomacy of first contact.

📖 BIOGRAPHY:

Chief Sequin Mettabesetts

(1480–1550)

Sachem of the Montauk Tribe

13th Great-Grandfather of Janet Kira Lessin

Chief Sequin Mettabesetts was born in 1480 in Montauk Village, Paum Man Ak E, present-day Long Island, New York. As Sachem of the Montaukett people, he governed during a time of tribal strength, long before the colonizing powers of Europe had taken firm root on Turtle Island.

As a spiritual and diplomatic leader, he helped guide his community through generations of peacekeeping, harvest, and coastal trade with other Algonquian nations. His legacy remains embedded in the land, the waters, and the traditions that his people stewarded for thousands of years.

He is the 13th great-grandfather of Janet Kira Lessin, a descendant who carries forward his wisdom through storytelling and ancestral honoring.

🔹 SECTION I: NORTHEAST LINEAGE – MONTAUK / MOHAWK

📖 Quashawan Montauk Matabesetts

(1475–1560)

Matriarch of the Montaukett People

13th Great-Grandmother of Janet Kira Lessin

Born in 1475 in Montauk Indian Village, Long Island, New York, Quashawan was part of the Montaukett and Matabesett bloodlines—carriers of Eastern Algonquian cultural traditions. As a matriarch, she would have preserved the ceremonial cycles, ecological wisdom, and oral histories that shaped her people for generations. She lived and died in her homeland, near Eaton’s Neck, anchoring her legacy in the sacred coastal lands.

📖 Chief Sequin Mettabesetts

(1480–1550)

Sachem of the Montauk Tribe

13th Great-Grandfather of Janet Kira Lessin

A dignified portrait in rich, oil-toned hues captures Chief Sequin Mettabesetts of the Montaukett tribe standing against a backdrop of wind-swept dunes and ocean spray. He wears traditional deerskin garments adorned with shells, beads, and wampum. His long hair flows like the sea breeze, and his eyes reflect calm wisdom and quiet strength. Behind him, the rising sun touches the Atlantic, symbolizing renewal, leadership, and the ancient relationship between his people and the land now known as Long Island. This image honors his role as sachem, peacekeeper, and guardian of ancestral memory.

Chief Sequin was born in Montauk Village and led the Montaukett people from the late 15th to the early 16th centuries. As a sachem, he was entrusted with diplomatic, spiritual, and territorial responsibilities. His name lives on as part of the interwoven tribal lineages that predate European colonization in the Northeast. He died in 1550, long before contact—but not before shaping generations that followed.

SEQUIN MEETS THE SETTLERS AT PAUM MAN AK E

This emotive painting portrays a respectful early encounter between Chief Sequin Mettabesetts and European settlers near the shores of Paum Man Ak E (Montauk). Chief Sequin stands at the center, holding a peace wampum belt as he addresses the visitors, who lower their weapons in recognition. Around him, Montaukett elders, women, and children observe the meeting from the edge of the forest, while a small colonial family stands nearby, hesitant but open. The meeting takes place under a sprawling sky, with the ocean behind them, capturing a moment of diplomacy, grace, and mutual recognition in the twilight of a land about to change forever.

This landscape portrait features four Native American men—leaders, warriors, and peacekeepers-who stand shoulder to shoulder, looking directly into the viewer’s eyes. Their expressions range from stoic to serene, their eyes deep with memory and strength. Each wears distinct tribal regalia reflecting different regions and periods: shell beads, feathers, copper medallions, and woven mantles. The background is softly painted with forest and river, hinting at ancestral lands from Montauk to Pamunkey. This image honors the male ancestors who carried the responsibilities of diplomacy, defense, and tradition.

📖 Sarah Rachel Phinney Root

(1512–1601)

Montauk Woman, Herbalist, Matriarch

12th Great-Grandmother of Janet Kira Lessin

DESCRIPTION:

A luminous oil portrait in classical realist style depicts Sarah Rachel Phinney Root, a Montauk woman and healer born in 1512. She wears a soft deerskin mantle embroidered with simple beadwork and a strand of polished shells at her neck. In one hand, she holds a bundle of native herbs—sage, sweetgrass, and goldenrod. Her gaze is calm, knowing, and maternal. Behind her, a forest of birch trees glows with early morning light, and the faint outline of a medicinal lodge can be seen in the background. This image honors her role as a matriarch and cultural bridge between Montauk sovereignty and the incursion of colonialism.

Born in Hampden County, Massachusetts, Sarah carried Montauk heritage into New England at a time of shifting borders and early exploratory contact. She likely served as a healer and culture-bearer, passing wisdom to the next generation as the old world gave way to a new one. She died in Connecticut in 1601, a living thread between sovereignty and colonization.

Set in a peaceful clearing near the Connecticut River, this painting shows Sarah Rachel Phinney Root kneeling beside a simple thatched lodge, offering a satchel of healing herbs to a young English woman and her sick child. Montauk children peer from behind the trees, watching quietly. Elders sit nearby, stringing medicinal plants, while colonial figures approach respectfully, weapons set aside. The atmosphere is reverent and still. The painting captures a moment of human care transcending cultural boundaries—when knowledge, not conquest, was shared between peoples in the fragile first light of colonization.

📖 Rachel Turney Sherwood

(1722–1799)

Mohawk Midwife and Lineage Holder

6th Great-Grandmother of Janet Kira Lessin

In this traditional oil portrait, Rachel Turney Sherwood stands poised with quiet strength. Dressed in a simple linen dress accented with beadwork and a woven shawl, she holds a bundle of swaddling cloth and herbal remedies—symbols of her dual role as midwife and healer. Her eyes reflect the wisdom of one who has helped bring countless lives into the world amid the hardships of colonialism. Behind her is a wooded trail leading southward, representing her journey from Mohawk territory in New York to the shifting frontier of North Carolina. The soft light around her face speaks of resilience, adaptation, and enduring ancestral purpose.

Born in Rye, New York, Rachel descended from Mohawk and possibly mixed bloodlines, and carried the Iroquoian heritage into the 18th century. A midwife and healer, she journeyed from colonial New York to North Carolina during a time of land loss and survival. Her descendants continued the legacy of inner strength and cross-cultural adaptation.

This landscape scene depicts Rachel Turney Sherwood attending a birth in a rustic homestead on the edge of the colonial frontier. Inside the cabin, a young white settler woman rests with her newborn while Rachel prepares a warm herbal poultice. Outside, Mohawk and colonial figures share the space in cautious peace—some helping fetch water, others tending livestock. The forest beyond is thick and shadowed, suggesting both danger and protection. A soft glow emanates from within the home, lighting Rachel’s face as she embodies the quiet grace of a woman trusted by both peoples. This image honors her role as a cultural bridge and bearer of life during a time of upheaval and migration.

In this moving group portrait, four Native American women gaze directly at the viewer, their faces lit with wisdom, tenderness, and quiet power. Each wears clothing that blends elegance with practicality—embroidered doeskin, woven sashes, beaded earrings, and herbal pouches. Their hairstyles and adornments reflect their tribal identities and matrilineal roles. Set against a backdrop of gentle trees and village silhouettes, the image evokes a sacred lineage of midwives, healers, and culture-bearers who nurtured entire generations through both abundance and hardship.

🔹 SECTION II: VIRGINIA LINEAGE – POWHATAN CONFEDERACY / PAMUNKEY

(In chronological order)

📖 Pau Pauwiske Nonoma “Morning Scent Flower”

(1517–1600)

Pamunkey Woman of the Powhatan Confederacy

13th Great-Grandmother of Janet Kira Lessin

This luminous oil portrait captures Pau Pauwiske Nonoma, a revered Pamunkey matriarch, standing by the riverbanks of her homeland. She wears a soft doeskin dress adorned with woven reeds and freshwater pearls. Her long, dark hair flows freely, caught in a gentle morning breeze. In her hands, she holds a basket of herbs and corn, representing sustenance and ceremony. The light of dawn frames her profile, highlighting her role as a wisdom-keeper, kinship guide, and spiritual mother in the generations before colonization arrived. Her gaze is calm and timeless, reflecting strength passed down through blood and earth.

Born at the confluence of the Staunton and Dan Rivers in Virginia, Pau Pauwiske was a wisdom-keeper within the Pamunkey community. As a matrilineal figure, she likely carried herbal, ceremonial, and kinship knowledge essential to her people’s survival. She died just before English colonists arrived at Jamestown.

This powerful landscape scene shows Pau Pauwiske leading a riverside ceremony with Pamunkey women and children gathered in a half circle. The Staunton and Dan Rivers merge in the background, as smoke rises gently from earthen pots. She kneels to place sacred herbs and shells into the water, blessing her people and the land. Behind her, elders chant, while young girls watch with awe, learning through witnessing. Unseen but approaching is the coming tide of colonization—yet in this moment, there is only peace, prayer, and connection to the Earth. The painting radiates ancestral strength and sacred continuity in a time just before history shifted.

📖 Chief Winanuska “Dashing Stream”

(1545–1570)

Pamunkey Chief of the Powhatan Confederacy

13th Great-Grandfather of Janet Kira Lessin

This commanding oil portrait shows Chief Winanuska standing regally in full Pamunkey leadership regalia. His garments are adorned with dyed quills, shell beads, and early copperwork, symbolizing trade and diplomacy. His strong profile is turned toward the eastern horizon, where morning light hints at both promise and encroaching change. Behind him flows the sacred James River, shimmering with ancestral memory. The portrait honors his role as a pre-Jamestown leader—one who ruled during a time of strength, tradition, and early contact with Europeans. His poise speaks to confidence, readiness, and vision in the face of the colonial tide.

Born near the sacred falls of the James River at Werowocomoco, Chief Winanuska governed the Pamunkey tribe in the mid-16th century. Oral tradition ties him to de Velasco’s heritage, suggesting early Iberian contact or intermarriage. His leadership predates Jamestown and the colonial wave that soon followed.

In this vivid landscape, Chief Winanuska greets a group of Iberian emissaries near Werowocomoco, the sacred capital of the Powhatan Confederacy. The scene is set beside the river falls, under tall trees where canoes rest and council fires burn. Winanuska stands with his warriors and elders, offering tobacco and ritual speech to the foreign guests, who come bearing gifts of cloth, metal, and caution. Behind the chief, tribal members observe with guarded interest, their faces lit by firelight and cloud-filtered sun. This is a moment of history before the record books—when diplomacy shaped destinies, and Indigenous sovereignty still held the center of the world.

📖 Chief Wahunsenacawh (Wahunsonacock / “Running Stream”)

(1545–1618)

Paramount Chief of the Powhatan Confederacy

12th Great-Granduncle of Janet Kira Lessin

This stately oil portrait depicts Chief Wahunsenacawh in his prime, adorned in a richly woven mantle of feathers, deerskin, and beads. His brow is marked with ochre and ceremonial lines, symbolizing his spiritual and political stature. The background features a soft rendering of the James River and the edge of Werowocomoco, his capital. His expression is wise, alert, and dignified—the face of a leader tasked with guiding more than thirty Algonquian-speaking nations through one of the most transformative moments in history. The portrait honors him not just as Pocahontas’s father, but as a strategist, diplomat, and protector of his people’s sovereignty.

Ruling over more than 30 Algonquian-speaking tribes in Tidewater Virginia, Wahunsenacawh unified what became known as the Powhatan Confederacy. He led during the arrival of the English, negotiated with John Smith, and sought to defend his people’s sovereignty. He was the father of Pocahontas and died in 1618, the same year she passed in England.

Set at the banks of the Pamunkey River, this historical painting captures the decisive moment when Chief Wahunsenacawh meets English envoys for the first time. He stands at the center of a grand council ring, surrounded by Powhatan chiefs, warriors, and advisors. Across from them, English officers—cloaked in dark wool and metal buckles—stand stiffly, uncertain but respectful. The fire crackles at the center of the gathering, casting flickers of light on painted shields, copper tools, and woven mats. In the trees above, crows and owls perch in silence. This image embodies the tension, diplomacy, and fateful curiosity that defined early colonial encounters.

📖 Princess Matoaka Pocahontas Rebecca

(1595–1617)

Daughter of Wahunsenacawh, Diplomatic Bridge to England

12th Great-Grandaunt of Janet Kira Lessin

Born in Werowocomoco, Matoaka—better known as Pocahontas—was the daughter of Chief Wahunsenacawh. Her life became a legend, but beneath the myth lies the story of a young woman who was used as a political figure, baptized Rebecca, and brought to the English court. She died at age 21 in Gravesend, England. Her story remains both sacred and tragic—a poignant reflection of the cost of colonization.

📖 PRINCESS MATOAKA – POCAHONTAS REBECCA POWHATAN

(1595–1617)

Diplomatic Daughter of Chief Wahunsenacawh

12th Great-Grandaunt of Janet Kira Lessin

This intimate oil portrait captures Pocahontas as she may have appeared before colonization, known by her birth name, Matoaka. Dressed in finely tanned deerskin adorned with shell and quillwork, she stands by the riverbanks of Werowocomoco, hair loose in the wind, her gaze calm and resolute. Her eyes hold the wisdom of the forest and the sorrow of what’s to come. Behind her, the Pamunkey River shimmers under early morning light. This portrait honors her true identity as a daughter of the Powhatan Confederacy—before captivity, before England, before the myth.

She was born as Matoaka in the village of Werowocomoco, on the banks of the Pamunkey River in what is now Virginia. To her family and tribe, she was known for her spirited nature, her curiosity, and her luminous presence—hence her nickname, Pocahontas, meaning “playful one.” The English would later rename her Rebecca after her Christian baptism, but her soul always belonged to the rivers and forests of her homeland.

Pocahontas was the daughter of Chief Wahunsenacawh (also known as Wahunsonacock), the paramount chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, which governed over more than thirty Algonquian-speaking tribes. As his favored child, she was trained not only in the roles of women—gathering, cooking, herbal healing—but also in the diplomatic arts. She listened closely during tribal councils and learned to read the silences between words. Long before she ever met the English, she was being prepared as a cultural bridge.

In this moving historical scene, Pocahontas stands between two worlds. On one side, her father’s emissaries hold baskets of maize, tobacco, and gourds; on the other, English settlers lower their muskets in cautious trust. She extends her hands with a gesture of peace, offering food to the colonists at Jamestown. Behind her, warriors and tribal elders watch silently, aware that the balance of power is shifting. The light of late afternoon glows through the clearing, illuminating the tension, hope, and sacred intention of a young woman trying to build a bridge where none existed.

That meeting came in 1607, when Powhatan warriors captured Captain John Smith. The oft-retold tale of Pocahontas saving him from execution—whether literal, symbolic, or mythologized—reflects her pivotal role in early colonial diplomacy. What is certain is that she mediated peace between her people and the Jamestown settlers, visiting the fort with gifts of food during times of hunger and negotiating safe passage for both cultures in times of crisis.

But her story does not end there.

In 1613, Pocahontas was kidnapped by English colonists, held hostage for over a year, and eventually baptized as Rebecca. During captivity, she met and married John Rolfe, a tobacco farmer whose success would fuel the colony’s economic survival. In 1616, she was taken to England as a symbol of the “tamed savage”—a tragic but revealing display of how Indigenous women were used as political tools.

This painting shows Pocahontas—now known as Rebecca Rolfe—standing in formal English attire among the stone arches of a London estate. Her embroidered gown and feathered headdress reflect the strange duality of her role: Indigenous emissary and colonial symbol. Though her posture is upright, her face carries a gentle sadness, as if she is looking beyond the court to the forests of her home. English courtiers flank her, some curious, others distant. This portrait evokes the cost of her transformation: from a free Powhatan child to a political prisoner, to a wife, mother, and symbol of empire. She died here, in England, at just 21 years old—but her legacy endures.

In court, she met King James I and Queen Anne, attended high society events, and was paraded as an emblem of colonial success. Yet behind the lace and English dresses lived a woman who had left her homeland, her people, and her name behind.

She died in March 1617, in Gravesend, England, just as she was preparing to return to Virginia. She was around 21 years old.

But Pocahontas never truly left. Her story has been distorted, romanticized, and misunderstood—but she remains, in essence, a symbol of survival, cultural bridging, and the cost of contact. Her blood may not run through every descendant, but her spirit echoes in every heart that seeks justice, peace, and truth.

This wide-format oil painting captures all eight Native American ancestors in a unified composition—men and women standing in solidarity, each gazing straight into the eyes of the future. Their faces are painted with reverence and realism, their bodies dressed in regalia worn for ceremony, leadership, or labor. Their presence feels alive, timeless, and unshakable. This image invites the viewer not to look at the ancestors, but to be seen by them—to remember, to reflect, and to carry forward the sacred story of who we are.