Paranormal Perceptions Presage Improvement

Janet tells how at eighteen months of age, Masons ritually evoked her spirit and how she stayed connected to the paranormal her whole life. Extraterrestrials revived her from the brutal rape she suffered at age four. They foretold her role in helping humanity survive and thrive. The ETs gave her what Campbell calls the “Call to Adventure” that would set her on her hero journey to win gifts for all humanity.

Janet: I went to work in Johnston Atoll in December of 1995. after my boyfriend, Jason, secured me a job there. In December 1996, I attended a ritual in the underwater base where I met and interacted with hundreds to thousands of extraterrestrials. I had two jobs, one on the surface and another in the underground base, primarily as an interpreter and mediator (peacekeeper) between humans and aliens, but with other duties when required. I tell my whole story in “The Dragon at the End of Time” series of books.

I worked as a civilian for the military from December 1995 to February 1997. While there, I met regularly and individually with extraterrestrials. I attended regular council meetings and helped coordinate major interplanetary meetings with humans (world leaders), humanoids, Anunnaki, Draco, Dragons, and other species in the underwater base. I worked as an interpreter, mediator and Earth Ambassador.

All the Atolls underwater by the islands in Johnston Atoll connect to each other through underground tunnels. Plus, you can teleport from one end to the other.

ETs freely come and go as they were there first and have agreed to collaborate with humans. Since I am telepathic, I was often used to communicate and interpret. When I am in contact telepathically, I access my hyper-self and connect to the universal computer (this is a loose translation of the process, but not exactly how things work, as these things are currently beyond human understanding).

Janet sees her journey as a prototype, an example of everyone who wishes to escape, albeit temporarily, from the “everyday” into the broader context of individual and collective spiritual development.

In 1996, a team of Grey Aliens and American soldiers abducted her from her dorm on Johnston Atoll in the Pacific. They took her from a USO to a base under the atoll. There, twelve-foot Nordic-looking extraterrestrial humans, the Anunnaki, marched behind her to meet a giant female dragon.

The Dragon readied Janet to speak for modern feminine Homo sapiens aspirations before the Galactic Federation. The Dragon opened Janet to the consciousness of Ninmah, Mother of Humanity, charged with creating a civilized civilization based on peace, love, and partnership. With this interview, Janet continues commission from the Council to help humanity ascend. She does so now, sharing her experiences and urging you to share yours.

Janet Kira Lessin tells how four-foot tall Greys and U.S. soldiers took her and her lover to an alien/U.S. Military underwater base beneath Johnston Atoll. The Greys wrapped their three-fingered, one-thumbed hands around her and carried her to a hovercraft on the shore. While being carried after the aliens plucked her from her bed while she was deep in sleep, she screamed.

But a Grey told her telepathically they’d cloaked her screams as she was in an energy field with them as they carried her. The Greys and soldier escorts brought her lover too and took him and Janet into the craft.

The craft took them to the base beneath the atoll. The Greys sat her in a metal chair while several of them operated on the boyfriend.

They then took Janet to a cavern, where a group of seven-foot large ETs from the Planet Nibiru dressed her, then had her stand in a circle of light. They said, aloud in English, she’d see the Great Dragon of Galactic Society, which quarantined Earth for its violence, planetary pollution and nukes in space.

Janet at first only stood at the level of the Grand Dragon’s claw, but the Dragon miniaturized herself to Janet’s level and communicated that she would help Janet and other light workers achieve peace on Earth, respect for all the consciousness here.

She now shares the elixir/wisdom she gained from her hero-journey to the non-ordinary. Janet concludes the description of her encounter with the Dragon and the Anunnaki beneath Johnston Atoll.

Future shows will detail Janet’s work as Ninmah’s embodiment in this time-space.

2009 ZETA GREY & U.S. BRASS MET on AKAU ISLAND (JOHNSTON ISLAND TERRITORY)

They stationed me on Johnston Atoll in December 1995 and there, during my contract with Kalama Services and Raytheon, is where I met the mother dragon that lives in the underground/underwater installation part of the base. Ebens (Grey ETs) and other grey types were there along with tall grey/mantis hybrids and two other types of grey aliens. They worked alongside human military.

In 2009 Serpo [Zeta Reticuli] Greys met U.S. Brass on AKAU ISLAND in U.S.’ JOHNSTON ATOLL Where Janet Lessin has revealed information about the Alien-U.S. underwater base

http://www.serpo.org/release32a.php

2009 EBEN Landing at AKAU ISLAND Appears at the Very TOP CENTER

ANONYMOUS: The EBENS made a visit on November 12, 2009 (Serpo Greys) to a remote location on Earth, the North Pacific Ocean desert island of JOHNSTON ATOLL/ISLAND. The EBENS paid us a kindly visit for 12 hours between 0600 and 1800 on this U.S. territory [U.S. military time, local].

We found and retrieve “Star Charts” inside the [Roswell “crash”] craft which were transcribed on thin black something similar to paper, an “X-ray of the Universe. One of the alien star charts/maps was of our galaxy, the Milky Way, which showed the outer reaches of our galaxy.

QUESTION: Because of the U.S. government’s official investigation, what was the SPECIFIC CAUSE determined to be of the crash landing of the two (2) Eben craft in July 1947 over The State of New Mexico?

ANONYMOUS: An electrical storm brought down the two (2) Eben ships in July 1947.

QUESTION: In the days immediately following the Roswell crash, Roswell folklore tells of a USN JAG coming to the base where the lone surviving Eben was being held in some kind of holding/jail cell and it was only by accident that the JAG employee saw him. Did this actually happen? WHERE and WHEN [date] did the Eben die? Is he buried HERE on EARTH—and if so, WHERE? Or was he taken back to SERPO for burial?

Also, a caller to “Coast 2 Coast” said he was surprised Ebens did not stage some kind of “rescue mission.” Was a “rescue mission” ever staged by the Ebens, yes or no? Or did they approach our government and simply ask for their fallen (dead) comrade’s back and allow the lone survivor to remain?

ANONYMOUS ANSWERS: They took the only surviving Eben to the Roswell base and placed in the lead’s custody intelligence officer. A military convoy then moved him to Los Alamos the next day. They isolated the Eben from almost everyone and eventually died at Los Alamos in 1952; President Truman saw him.

There was NOT a rescue mission ever staged by the Ebens. The only two (2) Eben craft that were near Earth crashed that night in 1947. EBE #1 did state that they sent a distress signal to their home planet SERPO, but it would take at least nine (9) months for the nearest rescue craft to reach them. EBE #1 died in 1952. They returned his body, along with his crewmates, to the Ebens in 1964 during the meeting in NM. They stored the Eben craft in Ohio and then moved to the Nevada Test Site (NTS].

Last month, on Thursday, November 12, 2009, a visit WAS made by the EBENS to a remote location on Earth, to the little-known North Pacific Ocean desert island of JOHNSTON ATOLL/ISLAND. The EBENS paid us a kindly visit for 12 hours between 0600 and 1800 on this U.S. territory [U.S. military time, local].

http://www.serpo.org/release32a.php

The meeting specifically occurred on AKAU ISLAND, which is the North Island of the sprawling JOHNSTON ATOLL system. The EBENS landed on a flat portion of the northwest sector of this island. There were 18 (eighteen) officials from around the world who met the EBENS.

They included the following [number of] representatives from our planet, Sol III:

1 = VATICAN

2 = UNITED NATIONS

9 = UNITED STATES AMERICA

• Broken down into

1 = WHITE HOUSE REPRESENTATIVE ~ OBAMA ADMINISTRATION

2 = U.S. INTELLIGENCE OFFICERS

1 = LINGUIST

5 = U.S. MILITARY REPRESENTATIVES

• Other Countries / Miscellaneous

1 = PEOPLE’s REPUBLIC of CHINA

1 = RUSSIAN FEDERATION

4 = INVITED SPECIAL GUESTS

= 18 TOTAL INVITED GUESTS

In addition, they exchanged a very special set of gifts. The EBENS provided us with six (6) gifts that would assist us in future technological developments. In return, the Vatican gave the EBENS two (2) 12th Century religious-themed paintings (see “End Notes”).

They set a future meeting date for November 2012, besides a previously scheduled official visit on Thursday, November 11, 2010, at the NTS.

(Janet’s Note: We don’t know if any of these meetings happened. However, there’s no reason to believe they did not as Johnston Atoll is so remote and at this time (April 2022) only a few wildlife scientists remain on the surface. However, I’ve been in the underground facility and I’m not sure how many people live or work there).

http://www.serpo.org/release32a.php

CRITICAL NOTE: the U.S. military manages the defense of JOHNSTON ATOLL; NONE of the islands are open to the public.

QUESTION: Do we possess tele-transporter or “flash drive” technology that we have appropriated/back-engineered from the Visitors, yes or no?

ANONYMOUS ANSWERS: Regarding your question regarding “tele-transporter” technology, the Ebens do NOT have this technology. They have mastered space travel and can venture through space, defying the time barrier.

Ebens use a “Universal Grid” system in traveling from one point of space to another. Their craft travel NEAR the speed of light. This enables their craft to go into an altered space-time chamber. That allows the point of DEPARTURE and the point of DESTINATION to become closer in real time. It is like folding space by making the two (2) points—departure and destination — become much closer. Ebens have been working to perfect this type of space travel—overcoming the time barrier—for well over 50,000 [of our] years. By now, they have, in fact, perfected this mode of space travel.

Although they gave us the basic BLUEPRINT for their craft, propulsion mechanism and overall operating system, we still don’t understand it. They use minerals that we simply don’t have here on Earth [Element 115 per Bob Lazar?]. One particular mineral, similar to uranium but not as radioactive—provides the extra power for their propulsion system. They also use a form of a SPACE DISPLACEMENT system, which basically causes a VACUUM in front of the propulsion that allows NOTHING to interfere with the created THRUST.

They use a vacuum chamber, which comprises a mini-nuclear reactor that forces some type of matter into space that deletes the molecules and causes that tiny portion of space to become a vacuum. They also use anti-matter in such a way as to force their propulsion system into “streams” [waves] of energy in front of their craft that enables the craft to move and flow much easier through space with no FRICTION from the ATMOSPHERE.

ANTARES STAR SYSTEM: HOMEWORLD FOR ONE OF THE ALIEN SPECIES PRESENTLY VISITING SOL III, EARTH!

http://www.serpo.org/release32c.php

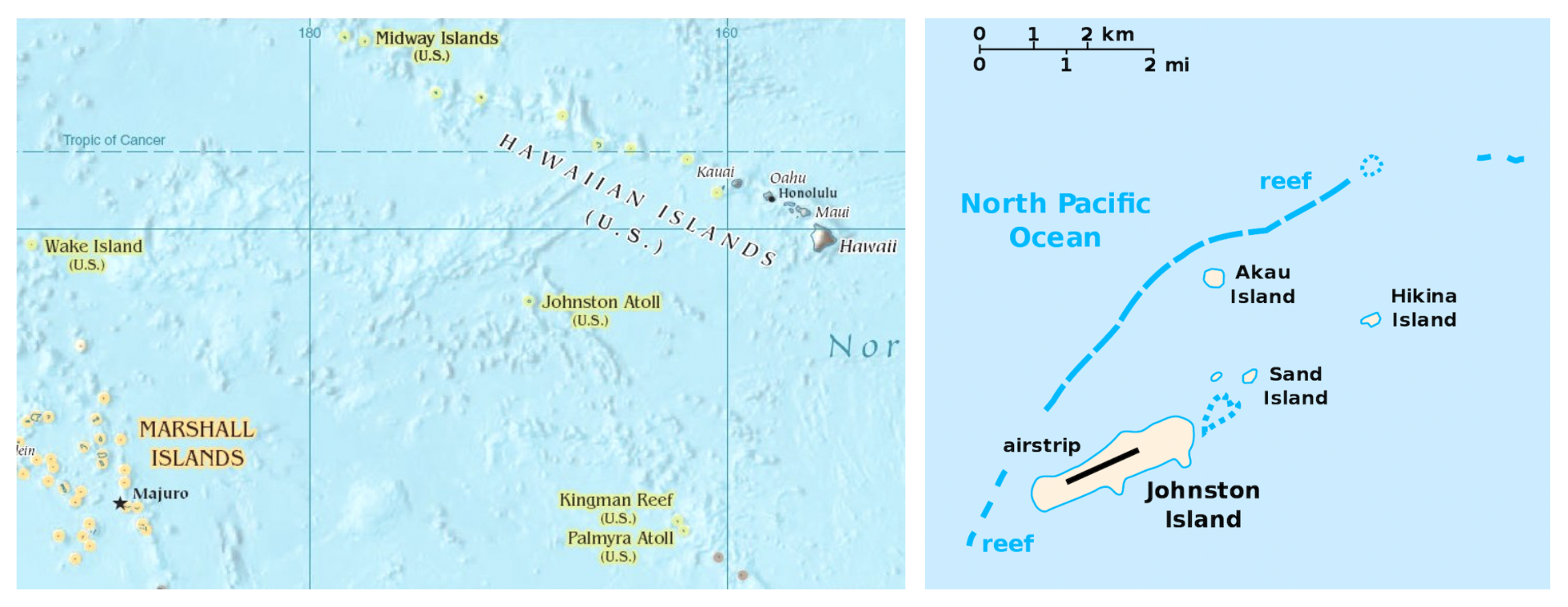

JOHNSTON ATOLL is a 50-square-mile atoll and is one of the MOST ISOLATED ATOLLS IN THE WORLD, in the North Central Pacific Ocean, some 750 miles southwest of Honolulu; the nearest lands to JOHNSTON ATOLL are the tiny islets of the French Frigate Shoals, around 800 km to the northeast, in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. It is about one-third of the way from Hawaii to the Marshall Islands.

They are located 16° 45′ North LATITUDE and 169° 30′ West LONGITUDE, there are four (4) islands on the coral reef platform, two natural islands—JOHNSTON ISLAND and SAND ISLAND—which were expanded by coral dredging, as well as North Island (AKAU) and East Island (HIKINA), both of which are artificial islands formed solely by coral dredging.

JOHNSTON ISLAND is an unincorporated territory of the United States, administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service of the Department of the Interior as part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument managed by the National Wildlife Refuge System. The defense of JOHNSTON ATOLL is managed by the U.S. military; NONE of the islands are open to the public.

It is a former ATOMIC TEST FACILITY and site for five (5) high-altitude nuclear tests during the 1960s called “STARFISH PRIME” grouped together as “Operation FISHBOWL” under the larger former classified project of “Operation DOMINIC.”

Map of JOHNSTON ATOLL/ISLANDS [The EBENS from the ZETA RETICULI Double Star System Landed on AKAU Island]

Johnston Atoll

https://authory.com/WilsondaSilva/Chemical-Atoll-A-Paradise-With-Gas-Masks

The strange case of Johnston Atoll, where chemical weapons and atomic tests share the azure waters with birds, tropical fish and green sea turtles.

By Wilson da Silva

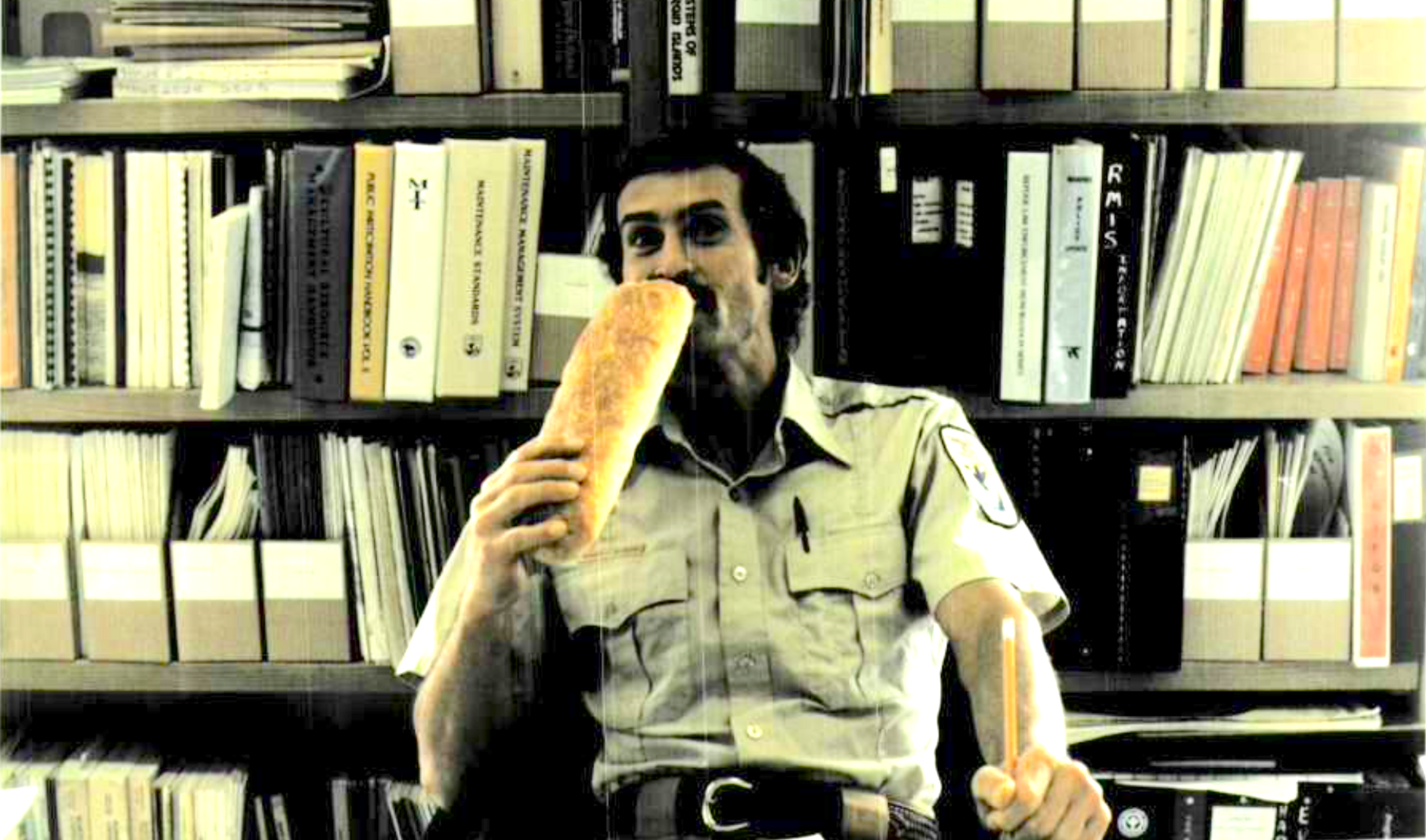

FROM THE AIR it is little more than a glorified aircraft carrier – an elongated islet of coral surrounded by a clear lagoon, small coral outcroppings and the dark asphalt of a runway cutting a swathe through the middle of the main island.

Yet, in what would otherwise be an idyllic setting, this remote corner of the Pacific is home to a nightmarish cocktail of death. It is Johnston Atoll, where 400,000 chemical weapons are stored, from where atomic tests were once conducted and where the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service runs one of the most bizarre animal refuges in the world.

Located 1,200 km southwest of Hawaii, Johnston Atoll is a United States military facility. Working for the international newswire Reuters, I joined 70 other journalists on the first press tour of the atoll. Security is tight – nobody gets within 80 km of the atoll without the military knowing about it.

There are four small islands set within the coral lagoon, where 500,000 birds visit and 301 species of fish swim the shallow waters. Johnston Island is the largest, followed by Sand, Akau and Hikina islands. All add up to some 80 square kilometres of land.

The atoll is a limestone cap sitting atop the core of an ancient volcanic island which began sinking slowly 86 million years ago. The coral is thousands of metres thick, and although the shallow reefs are lush with varied life, the deep surrounding ocean is a biological desert. The westward flowing North Equatorial Current which girdles the atoll carries few nutrients near the surface, and the microscopic plant life on which most other sea creatures depend is scarce beyond the island chain.

But the current is diverted by the underwater mountain that makes up the atoll, and the turbulence throws up nutrients from the deeper waters nearer to the surface. Like a plough, the atoll cuts through the current and throws up a cloud of organic material behind it, creating a wake of rich marine life to the west of the island on which thousands of sea birds come to feed.

It is the only dry land and shallow water for millions of square kilometres of cold ocean, and many of the island’s 1,300 human residents – mostly American civilians contracted to the military and on short stays – like to tell you that it is one of the most isolated places in the world.

Two endangered species can be found on the atoll, the green sea turtle and the Hawaiian monk seal. The turtles spend their entire lives at sea except for brief visits ashore to deposit their eggs in sandy pits dug in shallow areas above the high tide mark. Adult turtles grow to weigh some 130 to 180 kilos, and can take 40 years to reach breeding maturity. Tagging by researchers suggests the turtles probably nest at the French Frigate Shoals, small rock outcroppings that are part of the Hawaiian chain and lie 850 km to the north.

The seals are mostly found in the northwest Hawaiian islands, although some often appear at Johnston Atoll. Nine seals were moved to the atoll lagoon in 1984, but none have taken up permanent residence.

By far the most visible animal life is the birds. Half a million use the atoll, many migratory and originating in North America and northern Asia. there are shearwaters and petrels, tropicbirds, frigatebirds and boobies, terns and noddies, shorebirds and waterfowl.

Some are large, like the black-footed albatross which has a wingspan of 2.25 metres, while others are as small as the Townsend’s shearwater, which has a wingspan of 32 centimetres. There are 13 breeds nesting on the atoll, 17 migratory breeds,14 that are uncommon or rarely seen, and eight that accidentally find their way there. Breeding is normally conducted between February and September.

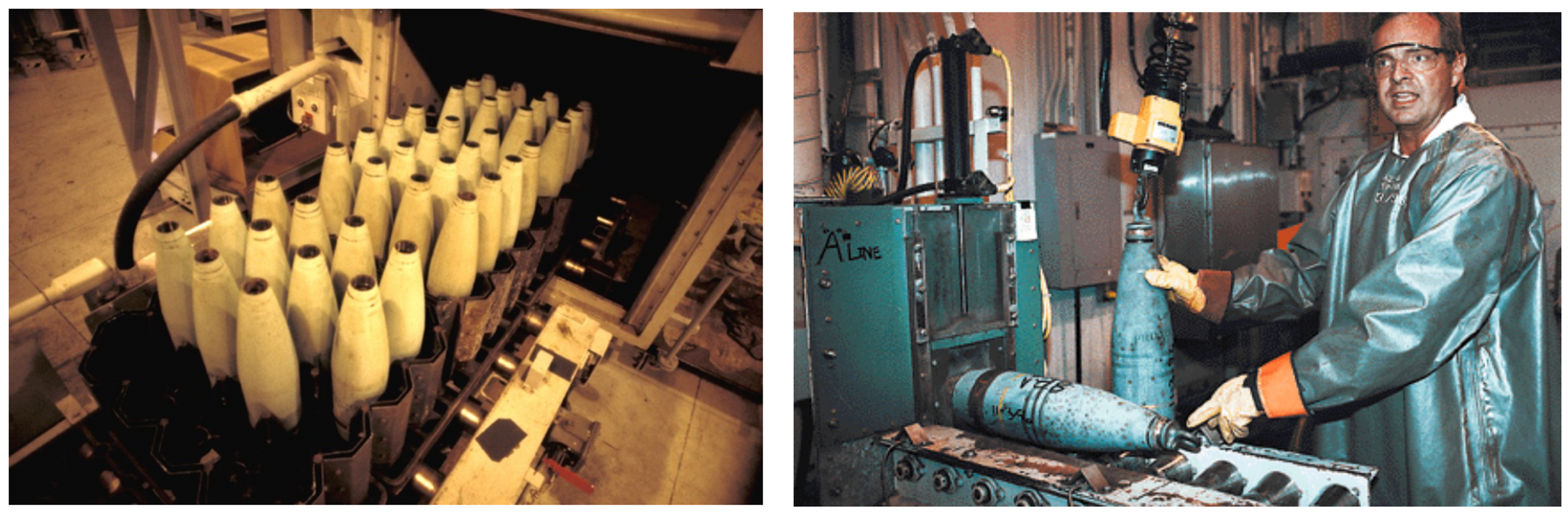

Gas masks and rubber suits

Although a biological oasis in an otherwise lifeless sea, Johnston Atoll is also the site for world’s largest chemical weapons destruction station. Here sit 54 storage bunkers, and buried in these metal and coral tombs are American missiles, mortars, bombs and land mines of chemical concoctions so feared they were never used in battle. So feared that in the 1970s the U.S. Congress outlawed their return to U.S. soil.

So here they stay, 6.6 percent of the United States’ chemical weapons stockpile, awaiting destruction mandated by a 1985 arms reduction treaty between the superpowers. Most of the 30,000 tonne American stockpile is to be obliterated by the end of the century under the treaty.

Hailed as a triumph in arms reduction, in reality many of the weapons on both sides are old and leaky, and had to be destroyed lest they contaminate military personnel. Another 104,000 chemical weapons from Germany were brought to the island last year, high-tech weapons that are the best in the U.S. inventory.

The incinerator facility dominates one section of Johnston Island, a towering lattice-work structure of metal pipes, girders and concrete sitting like a multi-storey petroleum refinery squeezed into a too-small piece of land.

When visiting the low-lying atoll, you must prepare for chemical warfare. You are fitted with a gas mask, carry nerve gas antidotes in self-propelled syringes and must be ready to jab yourself within seconds of an exposure alarm sounding.

The locals like you to think they take safety seriously on Johnston. This tends to be a good idea – a nerve agent like sarin, odourlous and colourless, seeps through clothing and skin and soon restricts breathing, triggers involuntary urination and defecation, brings on convulsions and finally death. Mustard gas raises watery blisters hours after skin contact, and inflames the nose and throat.

Had a contamination alarm sounded, nine seconds was all we had to attach gas masks to our faces. If we felt symptoms of poisoning, we were to jab our legs with the syringes, and make our way to one of the safety buildings on the island.

They trained us for chemical warfare, but when we stepped off the military plane clutching our gas masks, I was struck by the beauty of the place. The sun sparkles on the seawater and the 28 species of coral give the atoll waters a cool, cerulean tone. Johnston Island is dominated by man-made activity, but the three other islets stretch into the distance in a semi-circle, and masses of birds can be seen on them.

Biologist Roger Di Rosa, atoll ranger for the United States Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS), says that during the breeding season, the skies are blanketed with birds. Thirteen species nest on the island, and since dredging by the military expanded surface land in the 1960s, bird populations have increased.

“The greatest impact to the environment actually comes from the people who live here, and the infrastructure that’s needed to support them,” said Di Rosa. “That causes more a problem than the plant or the destruction of the weapons themselves. People are out on the lagoons and they’re boating or diving and they’re fishing, and that will cause an impact.”

Sewage is treated and then used as fertiliser on the human-inhabited areas of Johnston Island. Rubbish is burned or sent back for burial or recycling to the U.S. mainland, mostly California or Florida. Transport is largely via bicycle, and there are three for every resident on the island.

Cars are only used where necessary, and when worn-out, are burned to remove tyres and hosing, then buried in artificial reefs some way from the atoll. Di Rosa says this practice is safe and used elsewhere, only ferrous metals are sunk, and fish have started to aggregate around the artificial reef.

In every press handout, every briefing and every tour the military gave, environmental aspects were stressed. There are seven environmental professionals on the atoll, decisions are made in consultation with them and every effort is made to reduce the military’s impact on wildlife. They say Johnston Atoll complies with the strictest directives the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has set, and the atoll is a cleaner and more environmentally safe place than big U.S. cities like Los Angeles.

Why is the military so eager to be seen as “green”? The Johnston Atoll incinerator is a prototype, and another eight are to be built across the United States, adjacent to bunkers holding the remaining American chemical weapons. With local opposition rising, the military is keen to get Johnston Atoll right – to show how safe and environmentally friendly it can be to burn chemical weapons, even in your own backyard.

One U.S. Air Force officer asked me during lunch, why is the media so intent on painting Johnston Atoll as a chemical weapons dump with a deadly, nightmare incinerator? I suggested that even if the Johnston Atoll operation is squeaky clean, Americans had so often trashed the Pacific that, if one time out of 10 they get things right, everyone will suspect a rat and dig like hell to find it.

The USFWS owns the atoll, but the military operates it and helps to fund wildlife operations. Another biologist operates on the island, and the military have hired bird and fish experts from California and Massachussetts to study atoll life.

Di Rosa and the military make strange bedfellows. On an island from which nuclear atmospheric tests were launched until 1962, where Vietnam era Agent Orange has spilled into the sea and where the U.S. keeps 6.6 percent of its chemical weapons stockpile, he manages a wildlife refuge that was mandated into existence before scientists had even split the atom.

During the tour, a highly-ranked island resident told me: “You know, we’re not popular in Hawaii”. The newspapers in Honolulu made this plain, often quoting environmental activists who say an accident on the island would send a cloud of deadly nerve gas floating over the Pacific. The prevailing wind is from the south, and the Hawaiian islands lie to the north-east.

There are 15 independent nations in the Pacific, and none are pleased about what is being done on the atoll. They worry about emissions from smokestacks, that a plane crash on the incinerator or the bunkers could throw up a cloud of chemical gas over them, or that the atoll could become the world’s chemical weapons dumping ground, a global ‘backyard burner’ for hazardous wastes.

The military and USFWS admit a catastrophic plane crash could release chemical weapons into the air, but they prefer to quote the environmental impact statement completed before the construction of the incinerators. It says such a chance is “less than one in a million”.

A collision into the incinerator would only release the small amount of gas kept inside the facility at any one time. The bunkers are the reinforced type used to house explosives, and a direct hit would at worst release the contents of only a few bunkers. Under this scenario, few of the weapons would likely be breached, the military says. The explosives inside rockets and mortars have been removed, and only the chemical warheads are stored here.

Either way, the effect on the environment of such a catastrophe would depend on wind activity and direction – still air could allow gases to hang near the atoll and percolate into the local life. In the worst-case event, with all chemical weapons released under the worst possible conditions, a “death plume” would likely reach 23 km around the island, but could extend 100 to 120 km. Beyond this, the gases would fall below lethal concentrations.

Hawaii is 1,200 km northeast, and the Marshall Islands some 2,350 km southwest – outside of range. But one University of Hawaii scientist says under certain conditions, the plume may reach Hawaii, and environmentalists worry what contamination of the area’s fish would do to the food chain. And how do you prevent contaminated fish from ending up on the tables of nearby islanders?

It is the sort of thing that worries Pacific nations. Although a meeting of the South Pacific Forum in July 1990 agreed that chemical weapons should be destroyed, they urged the U.S. to dismantle the incinerator once stockpiles already on the island are eliminated.

Days before our tour, U.S. President George Bush flew to Hawaii and met 11 of the area’s leaders and representatives in what was dubbed a ‘Pacific Summit’. With plenty of flags, military bands and red carpet, Bush met them for two hours and later said his country “had no plans” to use the atoll to burn other chemical weapons or later use it to burn hazardous waste.

For many after the meeting, including some of the Pacific leaders, the question remained – what do you do with a US$420 million high-tech incinerator, once the weapons are incinerated in 1994? With civilian opposition to the planned incinerators growing in the U.S. mailand, speculation is rising that the U.S. Congress may buckle under pressure and take the easier political option of banishing all chemical weapons to Johnston Atoll.

Sometimes more Club Med than Pine Gap

Despite a feeling that the possibility of death is only a malfunction away, life can be pleasant on the atoll. It often appears a mixture of demilitarized zone and holiday resort – wire fences and palm trees, decontamination rooms and softball teams, armed military police and a nine-hole golf course.

“We’ve got a six-lane bowling alley, movies every night and softball is really popular,” Curtis Rodgers, a civilian technician, told me. “A lot of people fish out there. Scuba diving is excellent, and you can sail and waterski.”

I later lunched at Johnston’s Tiki Lounge, the atoll’s watering hole and the only pub in 1.3 million square kilometres of featureless ocean. From near the water’s edge on Johnston’s north side, I saw a windsurfer bearing into the breeze far away. Careful inspection revealed the windsurfer wore a familiar green pouch which I could only assume held, like mine, a gas mask and two syringes.

Life can sometimes seem more like Club Med than Pine Gap. Atoll residents have overnight golf tournaments, volleyball clinics, an Olympic-sized swimming pool, basketball games and a daily newsletter called The Breeze. A store sells souvenir t-shirts and caps, one amusing one proclaiming “Hard Rock Café, Johnston Atoll”.

Residents get 13 channels of cable television via satellite, watch first-release movies every night at an open-air cinema, and have dances every two weeks. At such events, the atoll’s 300 women are often beset by scores of eager men.

“It’s really a small town,” said Jake Sitters, a civilian clerk who has been on the island for 28 years. “Just about everybody knows everyone else, and everybody knows what everybody’s doing and who they’re doing it with.

“Sometimes not all the women turn up to the dances, so you just sit around with a bunch of guys around a table, drinking and talking stories and here’s all this good music going to waste.”

Women were at first not allowed on the atoll, ostensibly because it held stocks of Agent Orange, a Vietnam War era defoliant linked with birth defects. When stocks were destroyed in 1977, women began to arrive, and Sitters says the social tinderbox some had predicted did not eventuate. “At first, we thought we were going to have trouble, the men all vying to be the rooster. But it didn’t happen. We’ve had only two or three instances where guys have fought over a gal.”

Sitters, a 61-year-old Texan, is the owner of the island’s only dog, Patches. Black with small white blotches and of indeterminate breed, he brought her to the atoll when she was six weeks old, and it has lived with him ever since.

Twenty years ago, he befriended a Hawaiian monk seal he found lying on the beach. After a few careful approaches, they soon became friends and spent seven months playing by the water or on the island’s boat house ramp.

“We had a tremendous time,” he recalled. “I’d lay down on the concrete ramp and she’d come up, put her flippers over me, and nibble on my ears. If I saw her head out on the water, I’d just clap my hands, and boy, she’d come right in to me. One time she followed me to the barracks looking for me, scared the hell out of the guys.”

When Sitters returned from an overseas vacation, the seal was gone. “For the most part, life here is – I hate to say idyllic, but that’s what it has been for me. There’s just an endless amount of things to do, and anybody who complains there’s nothing to do on Johnston Island, it’s their fault they’re bored,” Sitters said.

It may seem idyllic, but it is not a resort. A failed nuclear missile launch nearly 30 years ago has left one section of the atoll contaminated by 230 grams of plutonium, and a large spill of Agent Orange in 1971 left one corner of Johnston sealed off. The military, keen to display its environmental credentials ever since the chemical weapons incinerator was installed, began a thorough clean-up of both contaminated zones in July.

They told the traveling press that their US$420 million high-tech incinerator was safe. So safe that 79 rockets, carrying warheads filled with a lethal nerve agent, were burnt while reporters were led through the destruction station.

At one stage, a temperature fluctuation in one furnace chamber forced the plant to shut down for 44 minutes. It was one of the nagging glitches that have kept the facility, the first of its kind in the world, operating for only 24 percent of the time expected. Six times since trial incinerations first began in June 1990, contamination alarms have sounded throughout the facility, only later to prove false. Conveyor belts that carry non-lethal munitions parts have repeatedly broken down.

“When the plant operates, it operates very well,” technical director Charles Baronian told reporters. “Because the problems are mechanical, I would primarily characterize it as a design flaw, but not a basic flaw.” He stressed to uneasy journalists that the breakdowns do not endanger the safety or integrity of the facility, and shutdowns only occur because site managers take no chances, even in non-critical breakdowns.

Throughout the island, 106 automated monitoring stations take 29,000 readings daily. They scan the air in workplaces and around the island, sounding alarms when they detect minute quantities of nerve agents or blister gas.

Colonel George McVeigh Jnr is the kind of ramrod-straight U.S. Air Force officer you would expect to be in command of the island. At the end of our press tour, when the sun began to set, we heard a bugle outside playing the Star-Spangled Banner as the U.S. flag was taken down. McVeigh stopped an answer to a journalist’s question mid-sentence, and stood at attention until the bugle stopped.

The civilian contractor operating the island is Raytheon, the U.S. company which built the Patriot missile interceptor that became a darling of television news footage during the Gulf War. Some 758,000 litres of fresh water are extracted from the sea every day, and the facility costs US$18 million a year to operate.

From bird sanctuary to atomic tests

Johnston atoll was discovered in 1796 by Captain Joseph Pierpont, an American commanding the brig Sally. There were no people on the atoll, and there is no record of Polynesians ever having reached the islands. It was named in 1807 by an eager young British lieutenant in honour of his captain, Charles J. Johnston, after the crew of the HMS Cornwallis briefly sighted the atoll while headed elsewhere.

The first serious study of the island’s ecology was in 1923, and the results led the United States to declare it a bird sanctuary. Eleven years later it was handed to the U.S. Navy, but the wildlife refuge provisions remained.

The Japanese briefly shelled the atoll on their way home after the bombing of Hawaii’s Pearl Harbour in 1941. Airlifts were conducted from the atoll during the Korean War in the early 1950s, and in 1958 it became a nuclear test site: three atmospheric and one underground atomic test was conducted at Johnston Atoll.

In the 1970s, ageing chemical weapons from Okinawa in Japan were transfered to Johnston, later joined by Agent Orange stocks which were eventually destroyed in 1977. Last year, 104,000 state-of-the-art chemical munitions from U.S. bases in Germany were shipped in, and a forgotten chemical dump on the Solomon Islands was dug up and brought to the atoll.

Although the schedule sees the incinerator, known as JACADS (Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System), operating until 1994, the recurring delays mean that it will now probably operate for a few years more. Once complete, the military says JACADS will be dismantled.

Or maybe it will be mothballed, just as the atoll’s capability to conduct atmospheric atomic tests has been maintained despite the superpowers signing the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1962.

Johnston Atoll

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaJump to navigationJump to search

| Johnston Atoll | |

|---|---|

| United States Minor Outlying Islands | |

| Unofficial flag | |

| Map of Johnston Atoll | |

Coordinates:  16°44′13″N 169°31′26″WCoordinates: 16°44′13″N 169°31′26″WCoordinates:  16°44′13″N 169°31′26″W 16°44′13″N 169°31′26″W | |

| Country | United States |

| Status | Unorganized, unincorporated territory |

| Claimed by U.S. | March 19, 1858 |

| Named for | Captain Charles James Johnston, HMS Cornwallis |

| Government | |

| • Type | Administered as a National Wildlife Refuge |

| • Body | United States Fish and Wildlife Service |

| • Superintendent | Laura Beauregard, Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.03 sq mi (2.67 km2) |

| • EEZ | 157,389 sq mi (407,635 km2) |

| Highest elevation (Sand Island) | 30 ft (10 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Pacific Ocean) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 0 |

| Time zone | UTC-10 (Hawaii–Aleutian Time Zone) |

| Geocode | 127 |

| ISO 3166 code | UM |

| Website | www.fws.gov/refuge/Johnston_Atoll/ |

Johnston Atoll is an unincorporated territory of the United States, currently administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Johnston Atoll is a National Wildlife Refuge and part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. It is closed to public entry, and limited access for management needs is only granted by Letter of Authorization from the United States Air Force and a Special Use Permit from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

For nearly 70 years, the isolated atoll was under the control of the U.S. military. During that time, it was variously used as a naval refueling depot, an airbase, a testing site for nuclear and biological weapons, a secret missile base, and a site for the storage and disposal of chemical weapons and Agent Orange. Those activities left the area environmentally contaminated, and monitoring continues.

The island is home to thriving communities of nesting seabirds and has significant marine biodiversity. USFWS teams carry out environmental monitoring and maintenance to protect the native wildlife.[1]

Contents

- 1Geography

- 2Climate

- 3Wildlife

- 4Flora

- 5History

- 5.1Early history

- 5.2National Wildlife Refuge since 1926

- 5.3Military control 1934–2004

- 5.4Sand Island seaplane base

- 5.5Airfield

- 5.6World War II 1941–1945

- 5.7Coast Guard mission 1957–1992

- 5.8National nuclear weapon test site 1958–1963

- 5.9Anti-satellite mission 1962–1975

- 5.10Baker–Nunn satellite tracking camera station

- 5.11Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center

- 5.12Biological warfare test site 1965–68

- 5.13Chemical weapon storage 1971–2001

- 5.14Agent Orange storage 1972–1977

- 5.15Chemical weapon demilitarization mission 1990–2000

- 5.16Closure and remaining structures

- 5.17Contamination and cleanup

- 5.18After closing

- 6Demographics

- 7Areas

- 8Launch facilities

- 9See also

- 10References

- 11External links

Geography[edit]

Johnston Atoll is located between the Marshall Islands and the Hawaiian Islands

With the exception of USFWS activity, Johnston Atoll is a deserted 1,300-hectare (3,200-acre) atoll in the North Pacific Ocean, located about 750 nautical miles (1,390 km; 860 mi) southwest of the island of Hawaiʻi, and is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands.[2] The atoll, which is located on a coral reef platform, has four islands. Johnston Island and Sand Island are both enlarged natural features, while Akau (North) and Hikina (East) are two artificial islands formed by coral dredging.[2] By 1964, dredge and fill operations had increased the size of Johnston Island to 596 acres (241 ha) from its original 46 acres (19 ha), increased the size of Sand Island from 10 to 22 acres (4.0 to 8.9 ha), and added the two new islands, North and East, of 25 and 18 acres (10.1 and 7.3 ha) respectively.[3]

The four islands compose a total land area of 2.67 square kilometers (1.03 square miles).[2] Due to the atoll’s tilt, much of the reef on the southeast portion has subsided. But even though it does not have an encircling reef crest, the reef crest on the northwest portion of the atoll does provide for a shallow lagoon, with depths ranging from 3 to 10 m (10 to 33 ft).Johnston Island has been significantly increased in size through coral dredging.

The climate is tropical but generally dry. Northeast trade winds are consistent and there is little seasonal temperature variation.[2] With elevation ranging from sea level to 5 m (16 ft) at Summit Peak, the islands contain some low-growing vegetation and palm trees on mostly flat terrain, and no natural fresh water resources.[2]

| Island | Size in 1942 (ha) | Final size in 1964 (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Johnston Island | 19 | 241 |

| Sand Island | 4 | 9 |

| North (Akau) Island | – | 10 |

| East (Hikina) Island | – | 7 |

| Total land area | 23 | 267 |

| Johnston Atoll | 13,000 | 13,000 |

Climate[edit]

It is a dry atoll with less than 20 inches (510 mm) of annual rainfall.[4]

| hideClimate data for Johnston Atoll | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 90 (32) | 89 (32) | 90 (32) | 90 (32) | 91 (33) | 100 (38) | 101 (38) | 100 (38) | 95 (35) | 95 (35) | 96 (36) | 89 (32) | 101 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 81.7 (27.6) | 81.7 (27.6) | 82.0 (27.8) | 82.8 (28.2) | 84.2 (29.0) | 85.6 (29.8) | 86.2 (30.1) | 86.6 (30.3) | 86.5 (30.3) | 85.8 (29.9) | 84.0 (28.9) | 82.5 (28.1) | 84.1 (29.0) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 73.1 (22.8) | 73.0 (22.8) | 73.2 (22.9) | 74.0 (23.3) | 75.3 (24.1) | 76.6 (24.8) | 77.3 (25.2) | 77.8 (25.4) | 77.6 (25.3) | 77.3 (25.2) | 75.7 (24.3) | 74.1 (23.4) | 75.4 (24.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 63 (17) | 63 (17) | 65 (18) | 65 (18) | 68 (20) | 69 (21) | 70 (21) | 70 (21) | 71 (22) | 68 (20) | 63 (17) | 62 (17) | 62 (17) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.15 (55) | 1.56 (40) | 2.49 (63) | 2.11 (54) | 1.32 (34) | 0.92 (23) | 1.32 (34) | 2.24 (57) | 2.37 (60) | 3.07 (78) | 4.00 (102) | 2.84 (72) | 26.4 (670) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[5] |

Wildlife[edit]

About 300 species of fish have been recorded from the reefs and inshore waters of the atoll. It is also visited by green turtles and Hawaiian monk seals. The possibility of humpback whales using the waters as a breeding ground has been suggested, albeit in small numbers and with irregular occurrences so far.[6] Many other cetaceans possibly migrate through the area, but the species being most notably confirmed is Cuvier’s beaked whales.[7]

Birds[edit]

Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer’s petrel, wedge-tailed shearwater, Christmas shearwater, white-tailed tropicbird, red-tailed tropicbird, brown booby, red-footed booby, masked booby, great frigatebird, spectacled tern, sooty tern, brown noddy, black noddy, and white tern. It is the world’s largest colony of red-tailed tropicbirds, with 10,800 nests in 2020.[8] It is visited by migratory shorebirds, including the Pacific golden plover, wandering tattler, bristle-thighed curlew, ruddy turnstone and sanderling.[9] The island, with its surrounding marine waters, has been recognised as an Important Bird Area by BirdLife International for its seabird colonies.[10]

Flora[edit]

The first list of plants catalogued on Johnston Atoll was published in 1931 in Vascular Plants of Johnston and Wake Islands based on collections of the Tanager Expedition on in 1923. Three species were described Lepturus repens, Boerhavia diffusa, and Tribulus cistoides. In 1930’s when the island was used for aviation activities for the war, Pluchea odorata was introduced from Honolulu. [11]

History[edit]

Early history[edit]

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796, when the Boston-based American brig Sally accidentally grounded on a shoal near the islands. The ship’s captain, Joseph Pierpont, published his experience in several American newspapers the following year giving an accurate position of Johnston and Sand Island along with part of the reef, but did not name or lay claim to the area.[12] The islands were not officially named until Captain Charles J. Johnston of the Royal Naval ship HMS Cornwallis sighted them on December 14, 1807.[13] The ship’s journal recorded: “on the 14th [December 1808] made a new discovery, viz. two very low islands, in lat. 16° 52′ N. long. 190° 26′ E., having a dangerous reef to the east of them, and the whole not exceeding four miles in extent”.[14]

In 1856, the United States enacted the Guano Islands Act, which allowed citizens of the United States to take possession of islands containing guano deposits. Under this act, William Parker and R. F. Ryan chartered the schooner Palestine specifically to find Johnston Atoll. They located guano on the atoll in March 1858 and proceeded to claim the island as U.S. territory.[15] In June of the same year, S. C. Allen, sailing on the Kalama under a commission from King Kamehameha IV of Hawaiʻi, landed on Johnston Atoll, removed the American flag, and claimed the atoll for the Kingdom of Hawaii. Allen named the atoll “Kalama” and the nearby smaller island “Cornwallis.”[16][17]

Returning on July 27, 1858, the captain of the Palestine again hoisted the American flag and tried to acquire the island in the name of the United States. The same day, the “derelict and abandoned” atoll was declared part of the domain of Kamehameha IV.[17] On its July visit, however, the Palestine left two crew members on the island to gather phosphate. Later that year, Kamehameha revoked the lease granted to Allen when he learned the atoll had been claimed previously by the United States.[15] However, this did not prevent the Hawaiian Territory from making use of the atoll or asserting ownership.

By 1890, the atoll’s guano deposits had been almost entirely depleted (mined out) by U.S. interests operating under the Guano Islands Act. In 1892, HMS Champion made a survey and map of the island, hoping that it might be suitable as a telegraph cable station. On January 16, 1893, the Hawaiian Legation at London reported a diplomatic conference over this temporary occupation of the island. However, the Kingdom of Hawaii was overthrown on January 17, 1893. When Hawaii was annexed by the United States in 1898, during the Spanish–American War, the name of Johnston Island was omitted from the list of Hawaiian Islands.[citation needed] On September 11, 1909, Johnston was leased by the Territory of Hawaii to a private citizen for fifteen years. A board shed was built on the southeast side of the larger island, and a small tramline run up onto the slope of the low hill, to facilitate the removal of guano. Apparently neither the quantity nor the quality of the guano was sufficient to pay for gathering it, so that the project was soon abandoned.[17]

National Wildlife Refuge since 1926[edit]

USS Tanager with members of the 1923 Tanager Expedition

The Tanager Expedition was a joint expedition, sponsored by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Bishop Museum of Hawaii, which visited the Atoll in 1923. The expedition to the atoll consisted of two teams accompanied by destroyer convoys, with the first departing Honolulu on July 7, 1923 aboard the USS Whippoorwill, which conducted the first survey of Johnston Island in the 20th century. Aerial survey and mapping flights over Johnston were conducted with a Douglas DT-2 floatplane carried on her fantail, which was hoisted into the water for takeoff. From July 10–22, 1923, the atoll was recorded in a pioneering aerial photography project. The USS Tanager left Honolulu on July 16 and joined up with the Whippoorwill to complete the survey and then traveled to Wake Island to complete surveys there.[18] Tents were pitched on the southwest beach of fine white sand, and a rather thorough biological survey was made of the island. Hundreds of sea birds, of a dozen kinds, were the principal inhabitants, together with lizards, insects, and hermit crabs. The reefs and shallow water abounded with fish and other marine life.[17]USS Whippoorwill

On June 29, 1926, by Executive Order 4467, President Calvin Coolidge established Johnston Island Reservation as a federal bird refuge and placed it under the control of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, as a “refuge and breeding ground for native birds.”[19] Johnston Atoll was added to the United States National Wildlife Refuge system in 1926, and renamed the Johnston Island National Wildlife Refuge in 1940.[20] The Johnston Atoll National Wildlife Refuge was established to protect the tropical ecosystem and the wildlife that it harbors.[21] However, the Department of Agriculture had no ships, and the United States Navy was interested in the atoll for strategic reasons, so with Executive Order 6935 on December 29, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt placed the islands under the “control and jurisdiction of the Secretary of the Navy for administrative purposes”, but subject to use as a refuge and breeding ground for native birds, under the United States Department of the Interior.

On February 14, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8682 to create naval defense areas in the central Pacific territories. The proclamation established “Johnston Island Naval Defensive Sea Area” which encompassed the territorial waters between the extreme high-water marks and the three-mile marine boundaries surrounding the atoll. “Johnston Island Naval Airspace Reservation” was also established to restrict access to the airspace over the naval defense sea area. Only U.S. government ships and aircraft were permitted to enter the naval defense areas at Johnston unless authorized by the Secretary of the Navy.

In 1990, two full-time U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service personnel, a Refuge Manager and a biologist, were stationed on Johnston Atoll to handle the increase in biological, contaminant, and resource conflict activities.[22]

After the military mission on the island ended in 2004, the Atoll was administered by the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. The outer islets and water rights were managed cooperatively by the Fish and Wildlife Service, with some of the actual Johnston Island land mass remaining under control of the United States Air Force (USAF) for environmental remediation and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA) for plutonium cleanup purposes. However, on January 6, 2009, under authority of section 2 of the Antiquities Act, the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument was established by President George W. Bush to administer and protect Johnston Island along with six other Pacific islands.[23] The national monument includes Johnston Atoll National Wildlife Refuge within its boundaries and contains 696 acres (2.82 km2) of land and over 800,000 acres (3,200 km2) of water area.[24] The Administration of President Barack Obama in 2014 extended the protected area to encompass the entire Exclusive Economic Zone, by banning all commercial fishing activities. Under a 2017 review of all national monuments extended since 1996, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke recommended to permit fishing outside the 12-mile limit.[25]

Military control 1934–2004[edit]

On December 29, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt with Executive Order 6935 transferred control of Johnston Atoll to the United States Navy under the 14th Naval District, Pearl Harbor, in order to establish an air station, and also to the Department of the Interior to administer the bird refuge. In 1948, the USAF assumed control of the Atoll.[26]

During the Operation Hardtack nuclear test series from April 22 to August 19, 1958, administration of Johnston Atoll was assigned to the Commander of Joint Task Force 7. After the tests were completed, the island reverted to the command of the US Air Force.[27]

From 1963 to 1970, the Navy’s Joint Task force 8 and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) held joint operational control of the island during high-altitude nuclear testing operations.[28]

In 1970, operational control was handed back to the Air Force until July 1973, when Defense Special Weapons Agency was given host-management responsibility by the Secretary of Defense.[28] Over the years, sequential descendant organizations have been the Defense Atomic Support Agency (DASA) from 1959 to 1971, the Defense Nuclear Agency (DNA) from 1971 to 1996, and the Defense Special Weapons Agency (DSWA) from 1996 to 1998. In 1998, Defense Special Weapons Agency, and selected elements of the Office of Secretary of Defense were combined to form the Defense Threat Reduction Agency (DTRA).[29] In 1999, host-management responsibility transferred from the Defense Threat Reduction Agency once again to the Air Force until the Air Force mission ended in 2004 and the base was closed.[28]

Sand Island seaplane base[edit]

Aerial approach to the former base on Johnston Island (top). The ship channel is visible as a darker blue area starting at left and continuing up around the right side of Johnston Island, with Sand Island on the near side (bottom).

In 1935, personnel from the US Navy’s Patrol Wing Two carried out some minor construction to develop the atoll for seaplane operation. In 1936, the Navy began the first of many changes to enlarge the atoll’s land area. They erected some buildings and a boat landing on Sand Island and blasted coral to clear a 3,600 feet (1,100 m) seaplane landing.[30] Several seaplanes made flights from Hawaii to Johnston, such as that of a squadron of six aircraft in November, 1935.

In November 1939, further work was commenced on Sand Island by civilian contractors to allow the operation of one squadron of patrol planes with tender support. Part of the lagoon was dredged and the excavated material was used to make a parking area connected by a 2,000-foot (610 m) causeway to Sand Island. Three seaplane landings were cleared, one 11,000 feet (3,400 m) by 1,000 feet (300 m) and two cross-landings each 7,000 feet (2,100 m) by 800 feet (240 m) and dredged to a depth of 8 feet (2.4 m). Sand Island had barracks built for 400 men, a mess hall, underground hospital, radio station, water tanks and a 100 feet (30 m) steel control tower.[30] In December 1943 an additional 10 acres (4.0 hectares) of parking was added to the seaplane base.[30]

On May 26, 1942, a United States Navy Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina wrecked at Johnston Atoll. The Catalina pilot made a normal power landing and immediately applied throttle for take-off. At a speed of about fifty knots the plane swerved to the left and then continued into a violent waterloop. The hull of the plane was broken open and the Catalina sank immediately.[31]

After the war on March 27, 1949, a PBY-6A Catalina had to make a forced landing during flight from Kwajalein to Johnston Island. The plane was damaged beyond repair and the crew of 11 was rescued nine hours later by a Navy ship which sank the plane by gunfire.[32]

During 1958, a proposed support agreement for Navy Seaplane operations at Johnston Island was under discussion though it was never completed because a requirement for the operation failed to materialize.[22]

Airfield[edit]

Main article: Johnston Island Air Force Base

By September 1941, construction of an airfield on Johnston Island commenced. A 4,000-foot (1,200 m) by 500-foot (150 m) runway was built together with two 400-man barracks, two mess halls, a cold-storage building, an underground hospital, a fresh-water plant, shop buildings, and fuel storage. The runway was complete by December 7, 1941, though in December 1943 the 99th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at the atoll and proceeded to lengthen the runway to 6,000 feet (1,800 m).[30] The runway was subsequently lengthened and improved as the island was enlarged.

During World War II Johnston Atoll was used as a refueling base for submarines, and also as an aircraft refueling stop for American bombers transiting the Pacific Ocean, including the Boeing B-29 Enola Gay.[33] By 1944, the atoll was one of the busiest air transport terminals in the Pacific. Air Transport Command aeromedical evacuation planes stopped at Johnston en route to Hawaii. Following V-J Day on August 14, 1945, Johnston Atoll saw the flow of men and aircraft that had been coming from the mainland into the Pacific turn around. By 1947, over 1,300 B-29 and B-24 bombers had passed through the Marianas, Kwajalein, Johnston Island, and Oahu en route to Mather Field and civilian life.

Following World War II, Johnston Atoll Airport was used commercially by Continental Air Micronesia, touching down between Honolulu and Majuro. When an aircraft landed it was surrounded by armed soldiers and the passengers were not allowed to leave the aircraft. Aloha Airlines also made weekly scheduled flights to the island carrying civilian and military personnel; in the 1990s there were flights almost daily, and some days saw up to three arrivals.[34] Just before movement of the chemical munitions to Johnston Atoll, the Surgeon General, Public Health Service, reviewed the shipment and the Johnston Atoll storage plans. His recommendations caused the Secretary of Defense in December 1970 to issue instructions suspending missile launches and all non-essential aircraft flights. As a result, Air Micronesia service was immediately discontinued, and missile firings were terminated with the exception of two 1975 satellite launches deemed critical to the island’s mission.[22]

There were many times when the runway was needed for emergency landings for both civil and military aircraft. When the runway was decommissioned, it could no longer be used as a potential emergency landing place when planning flight routes across the Pacific Ocean. As of 2003, the airfield at Johnston Atoll consisted of an unmaintained closed single 9,000 feet (2,700 m) asphalt/concrete runway 5/23, a parallel taxiway, and a large paved ramp along the southeast side of the runway.[34]

World War II 1941–1945[edit]

Main article: Shelling of Johnston and Palmyra

In February 1941 Johnston Atoll was designated as a Naval Defensive Sea Area and Airspace Reservation. On the day the Japanese struck Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, USS Indianapolis was out of her home port of Pearl Harbor, to make a simulated bombardment at Johnston Island. Japan’s strike at Pearl Harbor occurred as the ship was unloading marines, civilians and stores on the atoll.[35] On December 15, 1941, the atoll was shelled outside the reef by a Japanese submarine, which had been part of the attack on Pearl Harbor eight days earlier. Several buildings including the power station were hit, but no personnel were injured.[30]: 159 Additional Japanese shelling occurred on December 22 and 23, 1941. On all occasions, Johnston Atoll’s coastal artillery guns returned fire, driving off the sub.

In July 1942, the civilian contractors at the atoll were replaced by 500 men from the 5th and 10th Naval Construction Battalions, who expanded the fuel storage and water production at the base and built additional facilities. The 5th Battalion departed in January 1943.[30]: 159 In December 1943 the 99th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at the atoll and proceeded to lengthen the runway to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and add an additional 10 acres (4.0 ha) of parking to the seaplane base.[30]: 160

Coast Guard mission 1957–1992[edit]

Sand Island and former U.S. Coast Guard LORAN Station

On January 25, 1957, the Department of Treasury was granted a 5-year permit for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) to operate and maintain a Long Range Aid to Navigation (LORAN) transmitting station on Johnston Atoll. Two years later in December 1959, the Secretary of Defense approved the Secretary of the Treasury’s request to use Sand Island for U.S. Coast Guard LORAN A and C station sites. The USCG was granted permission to install a LORAN A and C station on Sand Island to be staffed by U.S. Coast Guard personnel through June 30, 1992. The permit for a LORAN station to operate on Johnston Island was terminated in 1962. On November 1, 1957, a new United States Coast Guard LORAN-A station was commissioned. By 1958, the Coast Guard LORAN Station at Johnston Island began transmitting on a 24-hour basis, thus establishing a new LORAN rate in the Central Pacific. The new rate between Johnston Island and French Frigate Shoals gave a higher order of accuracy for fixing positions in the steamship lanes from Oahu, Hawaii, to Midway Island. In the past, this was impossible in some areas along this important shipping route. The original U.S. Coast Guard LORAN-A Station on Johnston Island ceased operations on June 30, 1961 when the new station on nearby Sand Island began transmitting using a larger 180 foot antenna.

The LORAN-C station was disestablished on July 1, 1992, and all Coast Guard personnel, electronic equipment, and property departed the atoll that month. Buildings on Sand Island were transferred to other activities. LORAN whip antennas on Johnston and Sand Islands were removed, and the 625-foot LORAN tower and antenna were demolished on December 3, 1992. The LORAN A and C station and buildings on Sand Island were then dismantled and removed.[36][37]

National nuclear weapon test site 1958–1963[edit]

See also: Operation Fishbowl, Operation Dominic, and Operation Hardtack I

Successes[edit]

Between 1958 and 1975, Johnston Atoll was used as an American national nuclear test site for atmospheric and extremely high-altitude nuclear explosions in outer space. In 1958, Johnston Atoll was the location of the two “Hardtack I” nuclear tests firings. One conducted August 1, 1958 was codenamed “Hardtack Teak” and one conducted August 12, 1958 was codenamed “Orange.” Both tests detonated 3.8-megaton hydrogen bombs launched to high altitudes by rockets from Johnston Atoll.

Johnston Island was also used as the launch site of 124 sounding rockets going up as high as 1,158 kilometers (720 miles). These carried scientific instruments and telemetry equipment, either in support of the nuclear bomb tests, or in experimental antisatellite technology.[38][39]Array of sounding rockets with instruments for making scientific measurements of high-altitude nuclear tests during liftoff preparations in the Scientific Row area on Johnston Island

Eight PGM-17 Thor missiles deployed by the U.S. Air Force (USAF) were launched from Johnston Island in 1962 as part of “Operation Fishbowl,” a part of “Operation Dominic” nuclear weapons tests in the Pacific. The first launch in “Operation Fishbowl” was a successful research and development launch with no warhead. In the end, “Operation Fishbowl” produced four successful high-altitude detonations: “Starfish Prime,” “Checkmate,” “Bluegill Triple Prime,” and “Kingfish.” In addition, it produced one atmospheric nuclear explosion, “Tightrope.”

On July 9, 1962, “Starfish Prime” had a 1.4-megaton explosion, using a W49 warhead at an altitude of about 400 kilometers (250 miles). It created a very brief fireball visible over a wide area, plus bright artificial auroras visible in Hawaii for several minutes. “Starfish Prime” also produced an electromagnetic pulse that disrupted some electric power and communication systems in Hawaii. It pumped enough radiation into the Van Allen belts to destroy or damage seven satellites in orbit.

The final Fishbowl launch that used a Thor missile carried the “Kingfish” 400-kiloton warhead up to its 98-kilometer (61 mi) detonation altitude. Although it was officially one of the Operation Fishbowl tests, it is sometimes not listed among high-altitude nuclear tests because of its lower detonation altitude. “Tightrope” was the final test of Operation Fishbowl and detonated on November 3, 1962. It launched on a nuclear-armed Nike-Hercules missile and was detonated at a lower altitude than the other tests:

“At Johnston Island, there was an intense white flash. Even with high-density goggles, the burst was too bright to view, even for a few seconds. A distinct thermal pulse was felt on bare skin. A yellow-orange disc was formed, and transformed itself into a purple doughnut. A glowing purple cloud was faintly visible for a few minutes.”[40] The nuclear yield was reported in most official documents as “less than 20 kilotons.” One report by the U.S. government reported the yield of the “Tightrope” test as 10 kilotons.[41] Seven sounding rockets were launched from Johnston Island in support of the Tightrope test, and this was the final American nuclear atmospheric test.

Failures[edit]

Nuclear-armed Thor missile explodes and burns on the launch pad at Johnston Island during the failed “Bluegill Prime” nuclear test, July 25, 1962

The “Fishbowl” series included four failures, all of which were deliberately disrupted by range safety officers when the missiles’ systems failed during launch and were aborted. The second launch of the Fishbowl series, “Bluegill“, carried an active warhead. Bluegill was “lost” by a defective range safety tracking radar and had to be destroyed 10 minutes after liftoff even though it probably ascended successfully. The subsequent nuclear weapon launch failures from Johnston Atoll caused serious contamination to the island and surrounding areas with weapons-grade plutonium and americium that remains an issue to this day.

The failure of the “Bluegill” launch created in effect a dirty bomb but did not release the nuclear warhead’s plutonium debris onto Johnston Atoll as the missile fell into the ocean south of the island and was not recovered. However, the “Starfish”, “Bluegill Prime”, and “Bluegill Double Prime” test launch failures in 1962 scattered radioactive debris over Johnston Island contaminating it, the lagoon, and Sand Island with plutonium for decades.[27][42]Johnston Island Launch Emplacement One (LE1) after a Thor missile launch failure and explosion contaminated the island with Plutonium during the Operation “Bluegill Prime” nuclear test, July, 1962

“Starfish“, a high altitude Thor launched nuclear test scheduled for June 20, 1962, was the first to contaminate the atoll. The rocket with the 1.45-megaton Starfish device (W49 warhead and the MK-4 re-entry vehicle) on its nose was launched that evening, but the Thor missile engine cut out only 59 seconds after launch. The range safety officer sent a destruct signal 65 seconds after launch, and the missile was destroyed at approximately 10.6 kilometers (6.6 miles) altitude. The warhead high explosive detonated in 1-point safe fashion, destroying the warhead without producing nuclear yield. Large pieces of the plutonium contaminated missile, including pieces of the warhead, booster rocket, engine, re-entry vehicle and missile parts, fell back on Johnston Island. More wreckage along with plutonium contamination was found on nearby Sand Island.

“Bluegill Prime,” the second attempt to launch the payload which failed last time was scheduled for 23:15 (local) on July 25, 1962. It too was a genuine disaster and caused the most serious plutonium contamination on the island. The Thor missile was carrying one pod, two re-entry vehicles and the W50 nuclear warhead. The missile engine malfunctioned immediately after ignition, and the range safety officer fired the destruct system while the missile was still on the launch pad. The Johnston Island launch complex was demolished in the subsequent explosions and fire which burned through the night. The launch emplacement and portions of the island were contaminated with radioactive plutonium spread by the explosion, fire and wind-blown smoke.Inspection of Thor rocket engine remains on Johnston Island after failure of “Bluegill Prime” nuclear test attempt, July 1962

Afterward, the Johnston Island launch complex was heavily damaged and contaminated with plutonium. Missile launches and nuclear testing halted until the radioactive debris was dumped and soils were recovered and the launch emplacement rebuilt. Three months of repairs, decontamination, and rebuilding the LE1 as well as the backup pad LE2 were necessary before tests could resume. In an effort to continue with the testing program, U.S. troops were sent in to do a rapid cleanup. The troops scrubbed down the revetments and launch pad, carted away debris and removed the top layer of coral around the contaminated launch pad. The plutonium-contaminated rubbish was dumped in the lagoon, polluting the surrounding marine environment. More than 550 drums of contaminated material were dumped in the ocean off Johnston from 1964 to 1965. At the time of the Bluegill Prime disaster, the top fill around the launch pad was scraped by a bulldozer and grader. It was then dumped into the lagoon to make a ramp, so the rest of the debris could be loaded onto landing craft to be dumped out into the ocean. An estimated 10 percent of the plutonium from the test device was in the fill used to make the ramp. Then the ramp was covered and placed into a 25 acres (100,000 m2) landfill on the island during 1962 dredging to extend the island. The lagoon was again dredged in 1963–1964 and used to expand Johnston Island from 220 acres (89 ha) to 625 acres (253 ha) recontaminating additional portions of the island.PGM-17 Thor missile at Johnston Island

On October 15, 1962 the “Bluegill Double Prime” test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that when the rocket was destroyed, it contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as “Safeguard C”. Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a “ready to test” above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed to be necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll “Safeguard C” mission, bringing it to an end.

Anti-satellite mission 1962–1975[edit]

Main article: Program 437

Program 437 turned the PGM-17 Thor into an operational anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon system, a capability that was kept top secret even after it was deployed. The Program 437 mission was approved for development by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara on November 20, 1962 and based at the Atoll. Program 437 used modified Thor missiles that had been returned from deployment in Great Britain and was the second deployed U.S. operational nuclear anti-satellite operation. Eighteen more suborbital Thor launches took place from Johnston Island during the 1964–1975 period in support of Program 437. In 1965–1966 four Program 437 Thors were launched with ‘Alternate Payloads’ for satellite inspection. This was evidently an elaboration of the system to allow visual verification of the target before destroying it. These flights may have been related to the late 1960s Program 922, a non-nuclear version of Thor with infrared homing and a high-explosive warhead. Thors were kept positioned and active near the two Johnston Island launch pads after 1964. However, partly because of the Vietnam War, in October 1970 the Department of Defense had transferred Program 437 to standby status as an economic measure. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks led to Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty that prohibited ‘interference with national means of verification’, which meant that ASAT’s were not allowed, by treaty, to attack Russian spy satellites. Thors were removed from Johnston Atoll and were stored in mothballed war-reserve condition at Vandenberg Air Force Base from 1970 until the anti-satellite mission of Johnston Island facilities was ceased on August 10, 1974, and the program was officially discontinued on April 1, 1975, when any possibility of restoring the ASAT program was finally terminated. Eighteen Thor launches in support of the Program 437 Alternate Payload (AP) mission took place from Johnston Atoll’s Launch emplacements.[39]

Baker–Nunn satellite tracking camera station[edit]

See also: Project Space Track and United States Space Surveillance Network

The Space Detection and Tracking System or SPADATS[43] was operated by North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) along with the U.S. Air Force Spacetrack system, The Navy Space Surveillance System and Canadian Forces Air Defense Command Satellite Tracking Unit. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory also operated a dozen 3.5 ton Baker-Nunn Camera systems (none at Johnston) for cataloging of man-made satellites. The U.S. Air Force had ten Baker-Nunn camera stations around the world mostly from 1960 to 1977 with a phase-out beginning in 1964.[44]

The Baker-Nunn space camera station was constructed on Sand Island and was functioning by 1965.[22] USAF 18th Surveillance Squadron operated the Baker-Nunn camera at a station built along the causeway on Sand Island until 1975 when a contract to operate the four remaining Air Force stations was awarded to Bendix Field Engineering Corporation. In about 1977, the camera at Sand Island was moved to Daegu, South Korea.[17] Baker-Nunn were rendered obsolete with the Initial Operational Capability of 3 GEODSS optical tracking sites at Daegu, Korea; Mount Haleakala, Maui and White Sands Missile Range. A fourth site was operational in 1985 at Diego Garcia and a proposed fifth site in Portugal was cancelled. The Daegu, Korea site was closed due to encroaching city lights. GEODSS tracked satellites at night, though the MIT Lincoln Laboratory test site, co-located with Site 1 at White Sands did track asteroids in daytime as proof of concept in the early 1980s.[44]

Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center[edit]

See also: SAMOS (satellite) and Mid-air retrievalA USAF JC-130 aircraft retrieving a SAMOS film capsule

Satellite and Missile Observation System Project (SAMOS-E) or “E-6” was a relatively short-lived series of United States visual reconnaissance satellites in the early 1960s. SAMOS was also known by the unclassified terms Program 101 and Program 201.[45] The Air Force program was used as a cover for the initial development of the Central Intelligence Agency‘s Key Hole (including Corona and Gambit) reconnaissance satellites systems.[46] Imaging was performed with film cameras and television surveillance from polar low Earth orbits with film canisters returning via capsule and parachute with mid-air retrieval. SAMOS was first launched in 1960, but not operational until 1963 with all of the missions being launched from Vandenberg AFB.[47]Corona film capsule recovery sequence. Credit: CIA Directorate of Science and Technology

During the early months of the SAMOS program it was essential not only to hide the Corona and GAMBIT technical efforts under a screen of SAMOS activity, but also to make the orbital vehicle portions of the two systems resemble one another in outward appearance. Thus, some of the configuration details of SAMOS were decided less by engineering logic than by the need to camouflage GAMBIT and thus, in theory, a GAMBIT could be launched without alerting many people to its real nature. Problems relative to tracking networks, communications, and recovery were resolved with the decision in late February 1961 to use Johnston Island as the film capsule descent and recovery zone for the program.[48] On July 10, 1961 work was initiated on four buildings of the Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center for the National Reconnaissance Office. Men from the Johnston Atoll facility would recover the parachuting film canister capsules with a radar equipped JC-130 aircraft by capturing them in the air with a specialized recovery apparatus.[49] The recovery center was also responsible for collecting the radioactive scientific data pods dropped from missiles following launch and nuclear detonation.[50]

Biological warfare test site 1965–68[edit]

See also: Project SHAD, Project 112, and Deseret Test Center

The atoll was subject to large-scale bioweapons testing over four years starting in 1965. The American strategic tests of bioweapons were as expensive and elaborate as the tests of the first hydrogen bombs at Eniwetok Atoll. They involved enough ships to have made the world’s fifth-largest independent navy. One experiment involved a number of barges loaded with hundreds of rhesus monkeys. It is estimated that one jet with bioweapon spray “would probably be more efficient at causing human deaths than a ten-megaton hydrogen bomb.”[51]

In the lead up to biological warfare testing in the Pacific under Project 112 and Project SHAD, a new virus was discovered during the Pacific Ocean Biological Survey Program by teams from the Smithsonian’s Division of Birds aboard a United States Army tugboat involved in the program. Initially, the name of that effort was to be called the Pacific Ornithological Observation Project but this was changed for obvious reasons.[52] First isolated in 1964 the tick-borne virus was discovered in Ornithodoros capensis ticks, found in a nest of common noddy (Anous stolidus) at Sand Island, Johnston Atoll. It was designated Johnston Atoll Virus and is related to influenza.[53]

In February, March, and April 1965 Johnston Atoll was used to launch biological attacks against U.S. Army and Navy vessels 100 miles (160 km) south-west of Johnston island in vulnerability, defense and decontamination tests conducted by the Deseret Test Center during Project SHAD under Project 112. Test DTC 64-4 (Deseret Test Center) was originally called “RED BEVA” (Biological EVAluation) though the name was later changed to “Shady Grove”, likely for operational security reasons. The biological agents released during this test included Francisella tularensis (formerly called Pasteurella tularensis) (Agent UL), the causative agent of tularemia; Coxiella burnetii (Agent OU), causative agent of Q fever; and Bacillus globigii (Agent BG).[54] During Project SHAD, Bacillus globigii was used to simulate biological warfare agents (such as anthrax), because it was then considered a contaminant with little health consequence to humans; however, it is now considered a human pathogen.[55] Ships equipped with the E-2 multi-head disseminator and A-4C aircraft equipped with Aero 14B spray tanks released live pathogenic agents in nine aerial and four surface trials in phase B of the test series from February 12 to March 15, 1965 and in four aerial trials in phase D of the test series from March 22 to April 3, 1965.[54]

According to Project SHAD veteran Jack Alderson who commanded the Army tugs, area three at Johnston Atoll was located at the most downwind part of the island and consisted of an collapsible Nissen hut to be used for weapons preparation and some communications.[56]

Chemical weapon storage 1971–2001[edit]

In 1970, Congress redefined the island’s military mission as the storage and destruction of chemical weapons. The United States Army leased 41 acres (17 ha) on the Atoll to store chemical weapons held in Okinawa, Japan. Johnston Atoll became a chemical weapons storage site in 1971 holding about 6.6 percent of the U.S. military chemical weapon arsenal.[42] The chemical weapons were brought from Okinawa under Operation Red Hat with the re-deployment of the 267th Chemical Company and consisted of rockets, mines, artillery projectiles, and bulk 1-ton containers filled with Sarin, Agent VX, vomiting agent, and blister agent such as mustard gas. Chemical weapons from West Germany and World War II era weapons from the Solomon Islands were also stored on the island after 1990.[57] Chemical agents were stored in the high security Red Hat Storage Area (RHSA) which included hardened igloos in the weapon storage area, the Red Hat building (#850), two Red Hat hazardous waste warehouses (#851 and #852), an open storage area, and security entrances and guard towers.