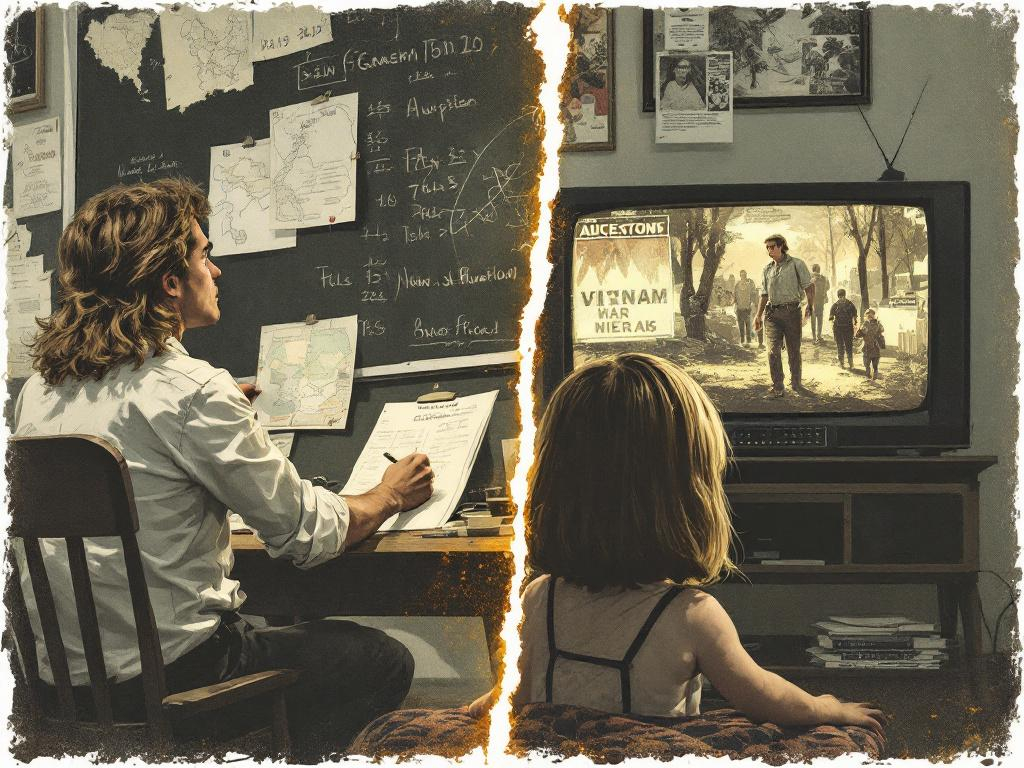

A 1960s American dining room at night. A black-and-white television glows with Vietnam War news. A young girl watches intently while adults sit silently, tense and conflicted.

VIETNAM THROUGH TWO LENSES: POWER, CHILDHOOD, AND THE WAR THAT CAPTURED A GENERATION

What It Looked Like from the Lecture Hall—and from the Dining Room Table

By Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D. (Anthropology, UCLA)

With Contributing Author Janet Kira Lessin

Wars do not erupt spontaneously. They are prepared for—psychologically, politically, and mythologically—long before the first bombs fall. Populations are conditioned to accept violence through carefully cultivated fear, selective storytelling, and moral simplifications that make resistance feel dangerous and obedience feel necessary. The Vietnam War remains one of the clearest modern examples of how this process works, not only at the level of governments and generals, but inside homes, classrooms, and the developing moral consciousness of an entire generation.

This account brings together two perspectives shaped by that war. One is analytical, formed by an anthropologist who, as a young college professor in Hawaii during the Vietnam era, observed how power manufactures consent through policy, media, and myth. The other is experiential, formed by a child fourteen years younger, sitting at a dining room table night after night, watching the war arrive through a television screen and learning—far too early—how death could be normalized through numbers.

Together, these perspectives reveal how domination consciousness operates both from above and from within, shaping not only public policy but private lives.

One of the decisive moments that propelled the United States into full-scale war in Vietnam occurred in August 1964, when the Johnson administration claimed that North Vietnamese forces had attacked U.S. naval vessels in the Gulf of Tonkin. The allegation—particularly the supposed second attack—was rushed through Congress as justification for the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, granting sweeping authority to escalate military action without a formal declaration of war. Later admissions and declassified materials revealed that no such second attack had occurred. Intelligence was misinterpreted, exaggerated, or invented, while covert U.S. operations against North Vietnamese coastal targets were already underway, undermining claims of unprovoked aggression.

Howard Zinn later documented this episode as a classic example of how governments manufacture justification for war while concealing their own provocations. What the government tells the public, he noted, often bears little resemblance to what actually happened. Vietnam did not begin as a defensive necessity; it began as a narrative necessity.

That narrative was reinforced daily through media. Wars are not fought only on battlefields; they are fought in newspapers, broadcasts, and classrooms. Sensational headlines transformed uncertainty into certainty and suspicion into outrage. Context disappeared. Doubt became disloyalty. Chris Harman placed Vietnam within a broader global pattern in which wars framed as moral crusades concealed struggles over power, influence, and economic control. Ordinary people were expected to sacrifice, while elites rarely bore the consequences. When fear becomes the organizing principle of public life, critical thinking is treated as treason.

For me, that media war arrived nightly. I was still a child, sitting at the dining room table, watching the evening news as the death count appeared on the screen. There were always more dead “enemy” than Americans. Even then, before I had the language to articulate it, that arithmetic felt wrong, as though human lives could be made acceptable by numerical comparison.

LIFE magazine arrived every week at our home, and I always read it first. One issue in particular, with its cover and most of its pages devoted to a single theme, was titled ONE WEEK’S DEAD. The photographs burned themselves into my memory. These were not abstractions. These were faces, bodies, lives interrupted midstream.

The boys in my class were already on a countdown. When they turned eighteen, they would be eligible for the draft, even though they did not yet have the right to vote. I watched them grow taller, broader, more confident, knowing that many of them were being quietly sorted toward something none of us could stop. I swallowed tears I did not yet know how to justify.

That fear became personal when my boyfriend, three years older than I was, graduated and began waiting for “the letter.” The summer they introduced the draft lottery—1969 or perhaps 1970—I watched the drawing on television, biting my fingernails down to the quick as each number was announced. When his number finally appeared, it was far down the line. The possibility that he might not be called lifted a heavy cloud from my shoulders.

Almost immediately, another realization followed. His relief meant that someone else’s son, someone else’s lover, someone else’s future husband would now be sent instead. Many of them would not come back. The system had not ended; it had merely redistributed risk and death. I remember asking myself how it was possible to feel relieved when so many others were being condemned by the same mechanism.

I was small, skinny, and young—a woman-child with no political standing, no platform, and no socially acceptable way to dissent. As the daughter of a Republican household, openly supporting the anti-war movement was not something I could safely articulate. Silence was safer. Observation was allowed. Feeling, however, was unavoidable.

It was in that quiet, constricted space that a commitment formed—one I did not yet have language for, but which would shape everything that followed. I committed to remembering what others tried to normalize. I refused to accept numerical justifications for human loss. I began, instinctively, to notice who benefited from war, who paid its costs, and who was discouraged from asking questions. My resistance was not loud or performative. It was internal. It was a refusal to stop seeing.

Resistance to the Vietnam War did arise, and it took many forms. Students, clergy, veterans, and families challenged the war’s legitimacy, often from deep moral conviction. Yet even resistance carried dangers. Opposing domination requires discipline. When resistance adopts the tools of domination—rage, coercion, dehumanization—it risks reproducing the very system it seeks to dismantle.

At the same time, one of the least acknowledged aspects of the Vietnam War was resistance from within the ranks themselves. GI underground newspapers, refusals of orders, equipment sabotage, and desertion revealed deep moral fractures inside the military. Many soldiers recognized that the war they were fighting bore little resemblance to the one politicians described. Clinical work with veterans showed that their trauma stemmed not only from combat, but from the realization that they had been used. When soldiers stop believing the story, the war is already lost, even if the bombing continues.

Vietnam exemplifies an ancient pattern of domination consciousness: obedience demanded, sacrifice normalized, dissent suppressed. In Enlil–Marduk terms, war functions as a control mechanism, dividing populations, exhausting resistance, and redirecting human creativity away from cooperation and toward destruction.

The tragedy of Vietnam was not only the war itself, but the vast human potential it consumed—potential that could have built schools, healed communities, and nurtured a partnership-based future. For some of us, that realization began in lecture halls. For others, it began at a dining room table. Either way, it began long before the war officially ended, and it has never fully let us go.

ILLUSTRATIONS (PLACED AT SECTION BREAKS OR BETWEEN PARAGRAPHS AS DESIRED)

THE DEATH COUNT

A 1960s American dining room at night. A black-and-white television glows with Vietnam War news. A young girl watches intently while adults sit silently, tense and conflicted.

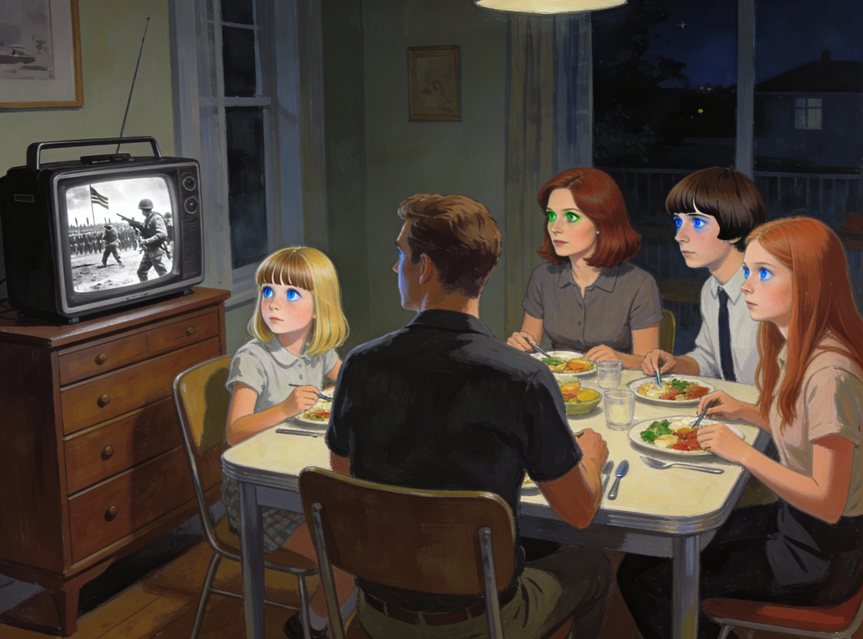

TWO GENERATIONS, ONE WAR

Description:

Split-scene image showing a young professor analyzing maps and dates at a chalkboard on one side, and a young girl watching Vietnam War news on television on the other, the scenes bleeding into one another.

Prompt:

Realistic conceptual illustration, split scene composition, 1960s college professor at chalkboard with maps and dates, young girl watching Vietnam War news on television, emotional continuity, subdued color palette, historical realism, landscape orientation.

THE WHOLE MISHBAHA™ (BELLS & WHISTLES)

🚧 Work in Progress

This article is part of an ongoing series examining war psychology, domination consciousness, partnership alternatives, and the long human shadow cast by manufactured conflict.

📬 Subscribe

👤 Author

Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D.

Anthropologist (UCLA), researcher, educator, and author exploring power, myth, and domination systems.

https://www.enkispeaks.com

👤 Contributing Author

Janet Kira Lessin

Writer, editor, researcher, and publisher focused on partnership consciousness, historical memory, and ethical witnessing.

https://www.dragonattheendoftime.com

https://substack.com/@janetalexlessinphd

🏷️ Tags

Vietnam War, Gulf of Tonkin, Draft Lottery, Howard Zinn, Chris Harman, Media Propaganda, Anti-War Movement, GI Resistance, Dominance Consciousness, Partnership Consciousness, Generational Memory, War Trauma, Manufactured Consent, Peace Studies

VIETNAM: SEEN FROM BOTH SIDES OF THE DINING ROOM TABLE

Two Generations, One Manufactured War, and the Cost of Believing the Story

By Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D. (Anthropology, UCLA)

With Contributing Author Janet Kira Lessin

🚧 WORK IN PROGRESS NOTE

This article is part of an ongoing series examining war psychology, domination consciousness, partnership alternatives, and the human cost of manufactured conflict. This version expands upon an earlier publication by adding lived generational testimony.

INTRODUCTION — TWO WITNESSES, ONE WAR

Wars do not erupt spontaneously. Authorities prepare us for them — psychologically, politically, and mythologically — long before the first bombs fall.

The Vietnam War stands as one of the clearest modern examples of how domination-consciousness operates: fear is cultivated, events are distorted, and entire populations are mobilized against their own long-term interests. The cost is measured not only in lives lost, but in generations traumatized and resources diverted away from healing, education, and shared prosperity.

This article brings together two vantage points.

One belongs to Sasha Alex Lessin, an anthropologist and young college professor in Hawaii during the Vietnam era, observing how power manufactures consent.

The other belongs to Janet Kira Lessin, fourteen years younger, still a child, watching the war unfold night after night on television — absorbing the arithmetic of death before having the language to question it.

Together, these perspectives reveal how war captures societies from the top down and from the inside out.

ILLUSTRATION 1

THE WAR ENTERS THE HOME

Description:

A 1960s American dining room at night. A family sits silently around a table while a black-and-white television glows in the background, displaying a news broadcast. A young girl watches intently, eyes fixed on the screen, while adults avert their gaze.

Prompt:

Realistic, cinematic illustration, 1960s American dining room at night, black-and-white television showing Vietnam War news, young girl watching intensely, adults silent, mid-century furniture, subdued lighting, emotional realism, documentary style, landscape orientation

GULF OF TONKIN — THE SPARK THAT WASN’T

(Sasha Alex Lessin)

Solomon Centers, a fictional 53-year-old scholar and counselor, stood quietly before a chalkboard marked with dates, naval routes, and arrows cutting through the Gulf of Tonkin.

Wars begin, he said calmly, when leaders decide the public must be frightened enough to accept them.

In August 1964, the Johnson administration claimed that North Vietnamese forces had attacked U.S. naval vessels. This allegation — especially the supposed second attack — was used to rush the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution through Congress, granting sweeping authority to escalate military action.

Later admissions revealed that no such second attack occurred. Intelligence was misinterpreted, exaggerated, or invented. Covert U.S. operations were already underway, undermining claims of unprovoked aggression.

Howard Zinn documented this as a classic case of manufactured justification — where what the government tells the public bears little resemblance to what actually happened.

MEDIA, FEAR, AND THE SELLING OF WAR

(Sasha Alex Lessin)

Wars are not only fought on battlefields. They are fought in newspapers, broadcasts, and classrooms.

Sensational headlines transformed uncertainty into certainty and suspicion into outrage. Context vanished. Doubt became disloyalty.

Chris Harman placed Vietnam within a broader pattern: wars framed as moral crusades often conceal struggles over power and control. Ordinary people sacrifice. Elites rarely do.

When fear becomes the organizing principle, critical thinking is treated as treason.

ILLUSTRATION 2

THE DEATH COUNT

Description:

A close-up of a 1960s television screen showing a Vietnam War casualty tally. Reflected in the glass is the face of a young girl, eyes wet but unblinking.

Prompt:

Photorealistic illustration, 1960s television close-up showing Vietnam War casualty numbers, reflection of a young girl’s face in the screen, emotional intensity, soft grain, muted colors, historical realism, landscape format

A CHILD WATCHING THE WAR

(Janet Kira Lessin)

While Sasha was a young college professor in Hawaii during the Vietnam War era, I was fourteen years younger and still a child.

I watched the nightly news from the dining room table as the death count appeared on the screen. There were always more dead “enemy” than Americans. Even then, that arithmetic felt wrong.

LIFE magazine arrived every week. One issue — its cover and most of its pages — was titled ONE WEEK’S DEAD. The images burned themselves into me.

The boys in my class were on a countdown. They would be drafted when they turned eighteen — even though they couldn’t yet vote.

I swallowed my tears watching these handsome boys, soon to be men, headed toward something none of us could stop.

THE LOTTERY

(Janet Kira Lessin)

My boyfriend, three years older, had already graduated and was waiting for “the letter.”

That summer — 1969 or 1970 — they instituted the draft lottery.

I watched it on television, biting my fingernails down to the quick. His number was far down the line. The cloud lifted.

Then it hit me.

That meant other young men — someone’s son, someone’s lover, someone’s future husband — would now be sent instead.

How could I be happy when so many were suffering?

I was a little, skinny, short woman-child.

What could I possibly do?

A QUIET COMMITMENT FORMED TOO EARLY

(Janet Kira Lessin)

There was no rally. No sign. No march.

There was only me realizing that relief could be morally complicated.

War wasn’t abstract. It was a sorting mechanism. A bureaucratic redistribution of death.

As the daughter of a Republican household, dissent had no safe outlet. Silence was safer. Observation was allowed.

So the commitment I made was internal.

I committed to remembering what others normalized.

To refusing numerical justifications for human loss.

To noticing who benefits, who pays, and who is told not to ask questions.

My commitment was not to protest loudly.

It was to never stop seeing.

RESISTANCE, FROM BOTH SIDES

(Sasha Alex Lessin)

Resistance arose — students, clergy, veterans, families. Many acted from deep moral conviction.

But Solomon Centers warned: opposing domination requires discipline. If resistance mirrors the violence it opposes, it reproduces the system it seeks to dismantle.

Meanwhile, soldiers themselves resisted — through refusals, underground newspapers, sabotage, desertion.

When soldiers stop believing the story, the war is already lost.

ILLUSTRATION 3

TWO GENERATIONS, ONE WAR

Description:

Split-scene image: on one side, a young professor at a chalkboard analyzing maps; on the other, a young girl watching television news. The scenes bleed into one another.

Prompt:

Conceptual realistic illustration, split scene composition, 1960s professor with chalkboard maps and dates, young girl watching Vietnam War news on television, emotional continuity, muted tones, historical realism, landscape orientation

DOMINATION VS PARTNERSHIP — THE DEEPER PATTERN

Vietnam exemplifies domination consciousness: obedience, sacrifice, silence.

Peace is not passive. It is an active refusal to accept lies, rage, and false choices.

The tragedy was not only the war — but how much human potential was consumed that could have built schools, healed communities, and nurtured a partnership-based future.

AUTHOR & CONTRIBUTOR

Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D.

Anthropologist, UCLA — Author

Janet Kira Lessin

Writer, Editor, Researcher — Contributing Author

www.dragonattheendoftime.com

https://substack.com/@janetalexlessinphd

TAGS

Vietnam War, Gulf of Tonkin, Draft Lottery, Howard Zinn, Chris Harman, Media Propaganda, Anti-War Movement, GI Resistance, Dominance Consciousness, Partnership Consciousness, Generational Memory, War Trauma, Manufactured Consent, Peace Studies

🔜 FOLLOW-UP ARTICLE (NEXT)

VENEZUELA: REHEARSING ANOTHER WAR BEFORE IT BEGINS

From Vietnam to MAGA, How Manufactured Enemies Keep the Machine Running

Core thesis:

The psychological and media patterns used to sell Vietnam are reappearing — fear amplification, demonization, false urgency, and moral simplification — now aimed at Venezuela and Latin America.

Sections:

- From Communism to “Socialism”: Recycling the Enemy

- Media Narratives and the New Gulf of Tonkin

- Why MAGA Needs a Foreign Threat

- What Vietnam Should Have Taught Us

- How to Refuse the Script