Francis Bacon

Sir Francis Bacon Tudor, 1st Viscount St Alban, Lord Verulam, William Shakespeare (1st cousin 13x removed)

1561–1626

BIRTH 22 JANUARY 1561 • The Strand, London, England

DEATH 9 APR 1626 • Highgate, London Borough of Camden, Greater London, England1st cousin 12x removed

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| The Right HonourableThe Viscount St AlbanPC | |

|---|---|

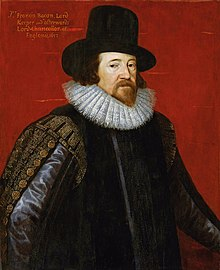

| Portrait by Paul van Somer I, 1617 | |

| Lord High Chancellor of England | |

| In office 7 March 1617 – 3 May 1621 | |

| Monarch | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Thomas Egerton |

| Succeeded by | John Williams |

| Attorney General of England and Wales | |

| In office 26 October 1613 – 7 March 1617 | |

| Monarch | James I |

| Preceded by | Sir Henry Hobart |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Yelverton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francis Bacon 22 January 1561 The Strand, London, England |

| Died | 9 April 1626 (aged 65) Highgate, Middlesex, England |

| Resting place | St. Michael’s Church, St. Albans |

| Spouse | Alice Barnham (m. 1604) |

| Parents | Sir Nicholas Bacon (father)Lady Anne Bacon (mother) |

| Education | Trinity College, Cambridge (no degree) Gray’s Inn (call to bar) |

| Notable works | Works by Francis Bacon |

| Signature | |

| Philosophy career | |

| Other names | Lord Verulam |

| Notable work | Novum Organum |

| Era | Renaissance philosophy17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Empiricism |

| Main interests | Natural philosophyPhilosophical logic |

| Notable ideas | showList |

| showInfluences | |

| showInfluenced | |

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban[a] PC, QC (/ˈbeɪkən/;[5] 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both natural philosophy and the scientific method and his works remained influential even in the late stages of the Scientific Revolution.[6]

‘Rare images’ takes a brief pictorial look at some of the powerful evidence revealing Francis Bacon as Shakespeare & the Supreme Head of the Rosicrucian-Freemasonry Brotherhood.

Bacon has been called the father of empiricism.[7] He argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature. He believed that science could be achieved by the use of a sceptical and methodical approach whereby scientists aim to avoid misleading themselves. Although his most specific proposals about such a method, the Baconian method, did not have long-lasting influence, the general idea of the importance and possibility of a sceptical methodology makes Bacon one of the later founders of the scientific method.

His portion of the method based in scepticism was a new rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, whose practical details are still central to debates on science and methodology. He is famous for his role in the scientific revolution, begun during the Middle Ages, promoting scientific experimentation as a way of glorifying God and fulfilling scripture. He was renowned as a politician in Elizabethan England, as he held the office of Lord Chancellor.

Bacon was a patron of libraries and developed a system for cataloguing books under three categories – history, poetry, and philosophy – which could further be divided into specific subjects and subheadings. About books he wrote, “Some books are to be tasted; others swallowed; and some few to be chewed and digested.”[8] The Shakespearean authorship thesis, which was first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Bacon wrote at least some and possibly all of the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare.[9]

Bacon was educated at Trinity College at the University of Cambridge, where he rigorously followed the medieval curriculum, which was presented largely in Latin. He was the first recipient of the Queen’s counsel designation, conferred in 1597 when Elizabeth I reserved him as her legal advisor. After the accession of James I in 1603, Bacon was knighted, then created Baron Verulam in 1618[2] and Viscount St Alban in 1621.[1][b] He had no heirs and so both titles became extinct on his death in 1626 at the age of 65. He died of pneumonia, with one account by John Aubrey stating that he had contracted it while studying the effects of freezing on meat preservation. He is buried at St Michael’s Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire.[11]

Biography[edit]

Early life and education[edit]

See also: Anne Bacon and Nicholas Bacon (Lord Keeper)

A young Francis Bacon depicted in a National Portrait Gallery painting; the inscription around Bacon’s head reads: Si tabula daretur digna animum mallem, Latin for “If one could but paint his mind”.

The Italianate entry to York House, built around 1626 in Strand, the year of Bacon’s death

Francis Bacon was born on 22 January 1561 at York House near Strand in London, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon (Lord Keeper of the Great Seal) by his second wife, Anne (Cooke) Bacon, the daughter of the noted Renaissance humanist Anthony Cooke. His mother’s sister was married to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, making Burghley Bacon’s uncle.[12]

Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health, which would plague him throughout his life. He received tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning toward Puritanism. He attended Trinity College at the University of Cambridge on 5 April 1573 at the age of 12,[13] living there for three years along with his older brother Anthony Bacon under the personal tutelage of Dr John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon’s education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. It was at Cambridge that Bacon first met Queen Elizabeth, who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him “The young lord keeper”.[14]

His studies brought him to the belief that the methods and results of science as then practised were erroneous. His reverence for Aristotle conflicted with his rejection of Aristotelian philosophy, which seemed to him barren, argumentative and wrong in its objectives.

On 27 June 1576, he and Anthony entered de societate magistrorum at Gray’s Inn. A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris, while Anthony continued his studies at home. The state of government and society in France under Henry III afforded him valuable political instruction.[15] For the next three years he visited Blois, Poitiers, Tours, Italy, and Spain.[16] There is no evidence that he studied at the University of Poitiers.[17] During his travels, Bacon studied language, statecraft, and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks. On at least one occasion he delivered diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, Leicester, and for the queen.[16]

The sudden death of his father in February 1579 prompted Bacon to return to England. Sir Nicholas had laid up a considerable sum of money to purchase an estate for his youngest son, but he died before doing so, and Francis was left with only a fifth of that money.[15] Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. To support himself, he took up his residence in law at Gray’s Inn in 1579,[15] his income being supplemented by a grant from his mother Lady Anne of the manor of Marks near Romford in Essex, which generated a rent of £46.[18]

Parliamentarian[edit]

Bacon’s statue at Gray’s Inn in London’s South Square

Bacon stated that he had three goals: to uncover truth, to serve his country, and to serve his church. He sought to achieve these goals by seeking a prestigious post. In 1580, through his uncle, Lord Burghley, he applied for a post at court that might enable him to pursue a life of learning, but his application failed. For two years he worked quietly at Gray’s Inn, until he was admitted as an outer barrister in 1582.[19]

His parliamentary career began when he was elected MP for Bossiney, Cornwall, in a by-election in 1581. In 1584 he took his seat in Parliament for Melcombe in Dorset, and in 1586 for Taunton. At this time, he began to write on the condition of parties in the church, as well as on the topic of philosophical reform in the lost tract Temporis Partus Maximus. Yet he failed to gain a position that he thought would lead him to success.[15] He showed signs of sympathy to Puritanism, attending the sermons of the Puritan chaplain of Gray’s Inn and accompanying his mother to the Temple Church to hear Walter Travers. This led to the publication of his earliest surviving tract, which criticized the English church’s suppression of the Puritan clergy. In the Parliament of 1586, he openly urged execution for the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots.

About this time, he again approached his powerful uncle for help; this move was followed by his rapid progress at the bar. He became a bencher in 1586 and was elected a Reader in 1587, delivering his first set of lectures in Lent the following year. In 1589, he received the valuable appointment of reversion to the Clerkship of the Star Chamber, although he did not formally take office until 1608; the post was worth £1,600 a year.[15][1]

In 1588 he became MP for Liverpool and then for Middlesex in 1593. He later sat three times for Ipswich (1597, 1601, 1604) and once for Cambridge University (1614).[20]

He became known as a liberal-minded reformer, eager to amend and simplify the law. Though a friend of the crown, he opposed feudal privileges and dictatorial powers. He spoke against religious persecution. He struck at the House of Lords in its usurpation of the Money Bills. He advocated for the union of England and Scotland, which made him a significant influence toward the consolidation of the United Kingdom; and he later would advocate for the integration of Ireland into the Union. Closer constitutional ties, he believed, would bring greater peace and strength to these countries.[21][22]

Final years of the Queen’s reign[edit]

Memorial to Bacon in the chapel of Trinity College, Cambridge

Bacon soon became acquainted with Robert Devereux, the 2nd Earl of Essex, Queen Elizabeth’s favourite.[23] By 1591 he acted as the earl’s confidential adviser.[15][23] In 1592, he was commissioned to write a tract in response to the Jesuit Robert Parson‘s anti-government polemic, which he titled Certain Observations Made upon a Libel, identifying England with the ideals of democratic Athens against the belligerence of Spain.[24] Bacon took his third parliamentary seat for Middlesex when in February 1593 Elizabeth summoned Parliament to investigate a Roman Catholic plot against her. Bacon’s opposition to a bill that would levy triple subsidies in half the usual time offended the Queen: opponents accused him of seeking popularity, and for a time the Court excluded him from favour.[25]

When the office of Attorney General fell vacant in 1594, Lord Essex’s influence was not enough to secure the position for Bacon and it was given to Sir Edward Coke. Likewise, Bacon failed to secure the lesser office of Solicitor General in 1595, the Queen pointedly snubbing him by appointing Sir Thomas Fleming instead.[1] To console him for these disappointments, Essex presented him with a property at Twickenham, which Bacon subsequently sold for £1,800.[26]

In 1597 Bacon became the first Queen’s Counsel designate, when Queen Elizabeth reserved him as her legal counsel.[27] In 1597, he was also given a patent, giving him precedence at the Bar.[28] Despite his designations, he was unable to gain the status and notoriety of others. In a plan to revive his position he unsuccessfully courted the wealthy young widow Lady Elizabeth Hatton.[29]

His courtship failed after she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to Sir Edward Coke, a further spark of enmity between the men.[30] In 1598 Bacon was arrested for debt. Afterward, however, his standing in the Queen’s eyes improved. Gradually, Bacon earned the standing of one of the learned counsels.[31] His relationship with the Queen further improved when he severed ties with Essex—a shrewd move, as Essex would be executed for treason in 1601.[32]

With others, Bacon was appointed to investigate the charges against Essex. A number of Essex’s followers confessed that Essex had planned a rebellion against the Queen.[33] Bacon was subsequently a part of the legal team headed by the Attorney General Sir Edward Coke at Essex’s treason trial.[33] After the execution, the Queen ordered Bacon to write the official government account of the trial, which was later published as A DECLARATION of the Practices and Treasons attempted and committed by Robert late Earle of Essex and his Complices, against her Majestie and her Kingdoms … after Bacon’s first draft was heavily edited by the Queen and her ministers.[34][35]

According to his personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, as a judge Bacon was always tender-hearted, “looking upon the examples with the eye of severity, but upon the person with the eye of pity and compassion”. And also that “he was free from malice”, “no revenger of injuries”, and “no defamer of any man”.[36]

James I comes to the throne[edit]

Bacon, c. 1618

The succession of James I brought Bacon into greater favour. He was knighted in 1603. In another shrewd move, Bacon wrote his Apologies in defense of his proceedings in the case of Essex, as Essex had favoured James to succeed to the throne. The following year, during the course of the uneventful first parliament session, Bacon married Alice Barnham.[37] In June 1607, he was at last rewarded with the office of solicitor general[1] and, in 1608, he began working as the Clerkship of the Star Chamber. Despite a generous income, old debts still could not be paid. He sought further promotion and wealth by supporting King James and his arbitrary policies. In 1610, the fourth session of James’s first parliament met. Despite Bacon’s advice to him, James and the Commons found themselves at odds over royal prerogatives and the king’s embarrassing extravagance. The House was finally dissolved in February 1611. Throughout this period Bacon managed to stay in the favor of the king while retaining the confidence of the Commons.

In 1613, Bacon was finally appointed attorney general, after advising the king to shuffle judicial appointments. As attorney general, Bacon, by his zealous efforts—which included torture—to obtain the conviction of Edmund Peacham for treason, raised legal controversies of high constitutional importance;[38] and successfully prosecuted Robert Carr, 1st Earl of Somerset, and his wife, Frances Howard, Countess of Somerset, for murder in 1616.

The so-called Prince’s Parliament of April 1614 objected to Bacon’s presence in the seat for Cambridge and to the various royal plans that Bacon had supported. Although he was allowed to stay, parliament passed a law that forbade the attorney general to sit in parliament. His influence over the king had evidently inspired resentment or apprehension in many of his peers. Bacon, however, continued to receive the King’s favour, which led to his appointment in March 1617 as temporary Regent of England (for a period of a month), and in 1618 as Lord Chancellor. On 12 July 1618 the king created Bacon Baron Verulam, of Verulam, in the Peerage of England; he then became known as Francis, Lord Verulam.[1]

Bacon continued to use his influence with the king to mediate between the throne and Parliament, and in this capacity he was further elevated in the same peerage, as Viscount St Alban, on 27 January 1621.[citation needed]

Lord Chancellor and public disgrace[edit]

Bacon and members of Parliament on the day of his 1621 political fall

Bacon’s public career ended in disgrace in 1621. After he fell into debt, a parliamentary committee on the administration of the law charged him with 23 separate counts of corruption. His lifelong enemy, Sir Edward Coke, who had instigated these accusations,[39] was one of those appointed to prepare the charges against the chancellor.[40] To the lords, who sent a committee to enquire whether a confession was really his, he replied, “My lords, it is my act, my hand, and my heart; I beseech your lordships to be merciful to a broken reed.” He was sentenced to a fine of £40,000 and committed to the Tower of London at the king’s pleasure; the imprisonment lasted only a few days and the fine was remitted by the king.[41] More seriously, parliament declared Bacon incapable of holding future office or sitting in parliament. He narrowly escaped undergoing degradation, which would have stripped him of his titles of nobility. Subsequently, the disgraced viscount devoted himself to study and writing.

There seems little doubt that Bacon had accepted gifts from litigants, but this was an accepted custom of the time and not necessarily evidence of deeply corrupt behaviour.[42] While acknowledging that his conduct had been lax, he countered that he had never allowed gifts to influence his judgement and, indeed, he had on occasion given a verdict against those who had paid him. He even had an interview with King James in which he assured:

The law of nature teaches me to speak in my own defence: With respect to this charge of bribery I am as innocent as any man born on St. Innocents Day. I never had a bribe or reward in my eye or thought when pronouncing judgment or order… I am ready to make an oblation of myself to the King

— 17 April 1621[43]

He also wrote the following to Buckingham:

My mind is calm, for my fortune is not my felicity. I know I have clean hands and a clean heart, and I hope a clean house for friends or servants; but Job himself, or whoever was the justest judge, by such hunting for matters against him as hath been used against me, may for a time seem foul, especially in a time when greatness is the mark and accusation is the game.[44]

As the conduct of accepting gifts was ubiquitous and common practice, and the Commons was zealously inquiring into judicial corruption and malfeasance, it has been suggested that Bacon served as a scapegoat to divert attention from the clandestine and favorite of King James I own ill practice and alleged corruption.[45]

The true reason for his acknowledgement of guilt is the subject of debate, but some authors speculate that it may have been prompted by his sickness, or by a view that through his fame and the greatness of his office he would be spared harsh punishment. He may even have been blackmailed, with a threat to charge him with sodomy, into confession.[42][46]

The British jurist Basil Montagu wrote in Bacon’s defense, concerning the episode of his public disgrace:

Bacon has been accused of servility, of dissimulation, of various base motives, and their filthy brood of base actions, all unworthy of his high birth, and incompatible with his great wisdom, and the estimation in which he was held by the noblest spirits of the age. It is true that there were men in his own time, and will be men in all times, who are better pleased to count spots in the sun than to rejoice in its glorious brightness. Such men have openly libelled him, like Dewes and Weldon, whose falsehoods were detected as soon as uttered, or have fastened upon certain ceremonious compliments and dedications, the fashion of his day, as a sample of his servility, passing over his noble letters to the Queen, his lofty contempt for the Lord Keeper Puckering, his open dealing with Sir Robert Cecil, and with others, who, powerful when he was nothing, might have blighted his opening fortunes for ever, forgetting his advocacy of the rights of the people in the face of the court, and the true and honest counsels, always given by him, in times of great difficulty, both to Elizabeth and her successor. When was a “base sycophant” loved and honoured by piety such as that of Herbert, Tennison, and Rawley, by noble spirits like Hobbes, Ben Jonson, and Selden, or followed to the grave, and beyond it, with devoted affection such as that of Sir Thomas Meautys.[47]

Personal life[edit]

Religious beliefs[edit]

Bacon was a devout Anglican. He believed that philosophy and the natural world must be studied inductively, but argued that we can only study arguments for the existence of God. Information on his attributes (such as nature, action, and purposes) can only come from special revelation. Bacon also held that knowledge was cumulative, that study encompassed more than a simple preservation of the past. “Knowledge is the rich storehouse for the glory of the Creator and the relief of man’s estate,” he wrote. In his Essays, he affirms that “a little philosophy inclineth man’s mind to atheism, but depth in philosophy bringeth men’s minds about to religion.”[48]

Bacon’s idea of idols of the mind may have self-consciously represented an attempt to Christianize science at the same time as developing a new, reliable scientific method; Bacon gave worship of Neptune as an example of the idola tribus fallacy, hinting at the religious dimensions of his critique of the idols.[49]

Bacon was against the splintering within Christianity, believing that it would ultimately lead to the creation of atheism as a dominant worldview, as indicated with his quote that “The causes of atheism are: divisions in religion, if they be many; for any one main division, addeth zeal to both sides; but many divisions introduce atheism.”[50]

Marriage to Alice Barnham[edit]

See also: Alice Barnham

Engraving of Alice Barnham

When he was 36, Bacon courted Elizabeth Hatton, a young widow of 20. Reportedly, she broke off their relationship upon accepting marriage to a wealthier man, Bacon’s rival, Sir Edward Coke. Years later, Bacon still wrote of his regret that the marriage to Hatton had not taken place.[51]

At the age of 45, Bacon married Alice Barnham, the 13-year-old daughter of a well-connected London alderman and MP. Bacon wrote two sonnets proclaiming his love for Alice. The first was written during his courtship and the second on his wedding day, 10 May 1606. When Bacon was appointed lord chancellor, “by special Warrant of the King”, Lady Bacon was given precedence over all other Court ladies. Bacon’s personal secretary and chaplain, William Rawley, wrote in his biography of Bacon that his marriage was one of “much conjugal love and respect”, mentioning a robe of honour that he gave to Alice and which “she wore unto her dying day, being twenty years and more after his death”.[36]

However, an increasing number of reports circulated about friction in the marriage, with speculation that this may have been due to Alice’s making do with less money than she had once been accustomed to. It was said that she was strongly interested in fame and fortune, and when household finances dwindled, she complained bitterly. Bunten wrote in her Life of Alice Barnham [52] that, upon their descent into debt, she went on trips to ask for financial favours and assistance from their circle of friends. Bacon disinherited her upon discovering her secret romantic relationship with Sir John Underhill, rewriting his will (which had generously planned to leave her lands, goods, and income) and revoking her entirely as a beneficiary.

Sexuality[edit]

Several authors believe that, despite his marriage, Bacon was primarily attracted to men.[53][54] Forker,[55] for example, has explored the “historically documentable sexual preferences” of both Francis Bacon and King James I and concluded they were both oriented to “masculine love”, a contemporary term that “seems to have been used exclusively to refer to the sexual preference of men for members of their own gender.”[56]

The well-connected antiquary John Aubrey noted in his Brief Lives concerning Bacon, “He was a Pederast. His Ganimeds and Favourites tooke Bribes”.[57] (“Pederast” in Renaissance diction meant generally “homosexual” rather than specifically a lover of minors; “ganimed” derives from the mythical prince abducted by Zeus to be his cup-bearer and bed warmer.)

The Jacobean antiquarian Sir Simonds D’Ewes (Bacon’s fellow Member of Parliament) implied there had been a question of bringing him to trial for buggery,[58] which his brother Anthony Bacon had also been charged with.[59]

In his Autobiography and Correspondence, in the diary entry for 3 May 1621, the date of Bacon’s censure by Parliament, D’Ewes describes Bacon’s love for his Welsh serving-men, in particular Godrick, a “very effeminate-faced youth” whom he calls “his catamite and bedfellow”.[60]

This conclusion has been disputed by others, who point to lack of consistent evidence, and consider the sources to be more open to interpretation.[33][61][62][63][64] Publicly, at least, Bacon distanced himself from the idea of homosexuality. In his New Atlantis, he described his utopian island as being “the chastest nation under heaven”, and “as for masculine love, they have no touch of it”.[65]

Death[edit]

Monument to Bacon at his burial place in St Michael’s Church in St Albans

On 9 April 1626, Francis Bacon died of pneumonia while at Arundel mansion at Highgate outside London.[66] An influential account of the circumstances of his death was given by John Aubrey’s Brief Lives.[66] Aubrey’s vivid account, which portrays Bacon as a martyr to experimental scientific method, had him journeying to High-gate through the snow with the King’s physician when he is suddenly inspired by the possibility of using the snow to preserve meat:

They were resolved they would try the experiment presently. They alighted out of the coach and went into a poor woman’s house at the bottom of Highgate hill, and bought a fowl, and made the woman exenterate it.

After stuffing the fowl with snow, Bacon contracted a fatal case of pneumonia. Some people, including Aubrey, consider these two contiguous, possibly coincidental events as related and causative of his death:

The Snow so chilled him that he immediately fell so extremely ill, that he could not return to his Lodging … but went to the Earle of Arundel’s house at Highgate, where they put him into … a damp bed that had not been layn-in … which gave him such a cold that in 2 or 3 days as I remember Mr Hobbes told me, he died of Suffocation.[67]

Aubrey has been criticized for his evident credulousness in this and other works; on the other hand, he knew Thomas Hobbes, Bacon’s fellow-philosopher and friend. Being unwittingly on his deathbed, the philosopher dictated his last letter to his absent host and friend Lord Arundel:

My very good Lord,—I was likely to have had the fortune of Caius Plinius the elder, who lost his life by trying an experiment about the burning of Mount Vesuvius; for I was also desirous to try an experiment or two touching the conservation and in-duration of bodies. As for the experiment itself, it succeeded excellently well; but in the journey between London and High-gate, I was taken with such a fit of casting as I know not whether it were the Stone, or some surfeit or cold, or indeed a touch of them all three. But when I came to your Lordship’s House, I was not able to go back, and therefore was forced to take up my lodging here, where your housekeeper is very careful and diligent about me, which I assure myself your Lordship will not only pardon towards him, but think the better of him for it. For indeed your Lordship’s House was happy to me, and I kiss your noble hands for the welcome which I am sure you give me to it. I know how unfit it is for me to write with any other hand than mine own, but by my troth my fingers are so disjointed with sickness that I cannot steadily hold a pen.[68]

Another account appears in a biography by William Rawley, Bacon’s personal secretary and chaplain:

He died on the ninth day of April in the year 1626, in the early morning of the day then celebrated for our Savior’s resurrection, in the sixty-sixth year of his age, at the Earl of Arundel’s house in Highgate, near London, to which place he casually repaired about a week before; God so ordaining that he should die there of a gentle fever, accidentally accompanied with a great cold, whereby the defluxion of rheum fell so plentifully upon his breast, that he died by suffocation.[69]

He was buried in St Michael’s church in St Albans. At the news of his death, over 30 great minds collected together their eulogies of him, which were then later published in Latin.[70] He left personal assets of about £7,000 and lands that realised £6,000 when sold.[71] His debts amounted to more than £23,000, equivalent to more than £4m at current value.[71][72]

Philosophy and works[edit]

Main article: Works by Francis Bacon

Sylva sylvarum, Bacon’s history of ten centuries

Front page of a 1651 copy of Sylva sylvarum

Francis Bacon’s philosophy is displayed in the vast and varied writings he left, which might be divided into three great branches:

- Scientific works in which his ideas for a universal reform of knowledge into scientific methodology and the improvement of mankind’s state using the Scientific method are presented.

- Religious and literary works in which he presents his moral philosophy and theological meditations.

- Juridical works in which his reforms in English Law are proposed.

Influence and legacy[edit]

Science[edit]

See also: Baconian method and Idola fori

Statue of Bacon in the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

National Portrait Gallery painting of the front cover of The History of Royal-Society of London, picturing Bacon (right) among the founding influences of Royal Society

Bacon’s seminal work Novum Organum was influential in the 1630s and 1650s among scholars, in particular Sir Thomas Browne, who in his encyclopedia Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–72) frequently adheres to a Baconian approach to his scientific enquiries. This book entails the basis of the scientific method as a means of observation and induction.

According to Bacon, learning and knowledge all derive from the basis of inductive reasoning. Through his belief in experimental encounters, he theorised that all the knowledge that was necessary to fully understand a concept could be attained using induction. In order to get to the point of an inductive conclusion, one must consider the importance of observing the particulars (specific parts of nature). “Once these particulars have been gathered together, the interpretation of Nature proceeds by sorting them into a formal arrangement so that they may be presented to the understanding.”[73] Experimentation is essential to discovering the truths of Nature. When an experiment happens, parts of the tested hypothesis are started to be pieced together, forming a result and conclusion. Through this conclusion of particulars, an understanding of Nature can be formed. Now that an understanding of Nature has been arrived at, an inductive conclusion can be drawn. “For no one successfully investigates the nature of a thing in the thing itself; the inquiry must be enlarged to things that have more in common with it.”[74]

Bacon explains how we come to this understanding and knowledge because of this process in comprehending the complexities of nature. “Bacon sees nature as an extremely subtle complexity, which affords all the energy of the natural philosopher to disclose her secrets.”[75] Bacon described the evidence and proof revealed through taking a specific example from nature and expanding that example into a general, substantial claim of nature. Once we understand the particulars in nature, we can learn more about it and become surer of things occurring in nature, gaining knowledge and obtaining new information all the while. “It is nothing less than a revival of Bacon’s supremely confident belief that inductive methods can provide us with ultimate and infallible answers concerning the laws and nature of the universe.”[76] Bacon states that when we come to understand parts of nature, we can eventually understand nature better as a whole because of induction. Because of this, Bacon concludes that all learning and knowledge must be drawn from inductive reasoning.

During the Restoration, Bacon was commonly invoked as a guiding spirit of the Royal Society founded under Charles II in 1660.[77][78] During the 18th-century French Enlightenment, Bacon’s non-metaphysical approach to science became more influential than the dualism of his French contemporary Descartes, and was associated with criticism of the Ancien Régime. In 1733 Voltaire introduced him to a French audience as the “father” of the scientific method, an understanding which had become widespread by the 1750s.[79] In the 19th century his emphasis on induction was revived and developed by William Whewell, among others. He has been reputed as the “Father of Experimental Philosophy”.[80]

He also wrote a long treatise on Medicine, History of Life and Death,[81] with natural and experimental observations for the prolongation of life.

One of his biographers, the historian William Hepworth Dixon, states: “Bacon’s influence in the modern world is so great that every man who rides in a train, sends a telegram, follows a steam plough, sits in an easy chair, crosses the channel or the Atlantic, eats a good dinner, enjoys a beautiful garden, or undergoes a painless surgical operation, owes him something.”[82]

In 1902 Hugo von Hofmannsthal published a fictional letter, known as The Lord Chandos Letter, addressed to Bacon and dated 1603, about a writer who is experiencing a crisis of language.

North America[edit]

A Newfoundland stamp, which reads: “Lord Bacon – the guiding spirit in colonization scheme”

Bacon played a leading role in establishing the British colonies in North America, especially in Virginia, the Carolinas and Newfoundland in northeastern Canada. His government report on “The Virginia Colony” was submitted in 1609. In 1610 Bacon and his associates received a charter from the king to form the Tresurer and the Companye of Adventurers and planter of the Cittye of London and Bristoll for the Collonye or plantacon in Newfoundland, and sent John Guy to found a colony there.[83] Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, wrote: “Bacon, Locke and Newton. I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences“.[84]

In 1910, Newfoundland issued a postage stamp to commemorate Bacon’s role in establishing the colony. The stamp describes Bacon as “the guiding spirit in Colonization Schemes in 1610”.[51] Moreover, some scholars believe he was largely responsible for the drafting, in 1609 and 1612, of two charters of government for the Virginia Colony.[85] William Hepworth Dixon considered that Bacon’s name could be included in the list of Founders of the United States.[86]

Law[edit]

Although few of his proposals for law reform were adopted during his lifetime, Bacon’s legal legacy was considered by the magazine New Scientist in 1961 as having influenced the drafting of the Napoleonic Code as well as the law reforms introduced by 19th-century British Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel.[87] The historian William Hepworth Dixon referred to the Napoleonic Code as “the sole embodiment of Bacon’s thought”, saying that Bacon’s legal work “has had more success abroad than it has found at home”, and that in France “it has blossomed and come into fruit”.[88]

Harvey Wheeler attributed to Bacon, in Francis Bacon’s Verulamium—the Common Law Template of The Modern in English Science and Culture, the creation of these distinguishing features of the modern common law system:

- using cases as repositories of evidence about the “unwritten law”;

- determining the relevance of precedents by exclusionary principles of evidence and logic;

- treating opposing legal briefs as adversarial hypotheses about the application of the “unwritten law” to a new set of facts.

As late as the 18th century, some juries still declared the law rather than the facts, but already before the end of the 17th century Sir Matthew Hale explained modern common law adjudication procedure and acknowledged Bacon as the inventor of the process of discovering unwritten laws from the evidences of their applications. The method combined empiricism and inductivism in a new way that was to imprint its signature on many of the distinctive features of modern English society.[89] Paul H. Kocher writes that Bacon is considered by some jurists to be the father of modern Jurisprudence.[90]

Bacon is commemorated with a statue in Gray’s Inn, South Square in London where he received his legal training, and where he was elected Treasurer of the Inn in 1608.[91]

More recent scholarship on Bacon’s jurisprudence has focused on his advocating torture as a legal recourse for the crown.[92] Bacon himself was not a stranger to the torture chamber; in his various legal capacities in both Elizabeth I’s and James I’s reigns, Bacon was listed as a commissioner on five torture warrants. In 1613(?), in a letter addressed to King James I on the question of torture’s place within English law, Bacon identifies the scope of torture as a means to further the investigation of threats to the state: “In the cases of treasons, torture is used for discovery, and not for evidence.”[93] For Bacon, torture was not a punitive measure, an intended form of state repression, but instead offered a modus operandi for the government agent tasked with uncovering acts of treason.

Organization of knowledge[edit]

Francis Bacon developed the idea that a classification of knowledge must be universal while handling all possible resources. In his progressive view, humanity would be better if access to educational resources were provided to the public, hence the need to organise it. His approach to learning reshaped the Western view of knowledge theory from an individual to a social interest.

The original classification proposed by Bacon organised all types of knowledge into three general groups: history, poetry, and philosophy. He did that based on his understanding of how information is processed: memory, imagination, and reason, respectively. His methodical approach to the categorization of knowledge goes hand-in-hand with his principles of scientific methods. Bacon’s writings were the starting point for William Torrey Harris‘s classification system for libraries in the United States by the second half of the 1800s.

The phrase “scientia potentia est” (or “scientia est potentia“), meaning “knowledge is power“, is commonly attributed to Bacon: the expression “ipsa scientia potestas est” (“knowledge itself is power”) occurs in his Meditationes Sacrae (1597).

Historical debates[edit]

Bacon and Shakespeare[edit]

Main articles: Bacon’s cipher and Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship

See also: Prince Tudor theory

The Baconian hypothesis of Shakespearean authorship, first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Francis Bacon wrote some or even all of the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare.[94]

Occult theories[edit]

Main article: Occult theories about Francis Bacon

See also: Idola theatri

An old volume of Bacon and a rose

Francis Bacon often gathered with the men at Gray’s Inn to discuss politics and philosophy, and to try out various theatrical scenes that he admitted writing.[95] Bacon’s alleged connection to the Rosicrucians and the Freemasons has been widely discussed by authors and scholars in many books.[62] However, others, including Daphne du Maurier in her biography of Bacon, have argued that there is no substantive evidence to support claims of involvement with the Rosicrucians.[96] Frances Yates[97] does not make the claim that Bacon was a Rosicrucian, but presents evidence that he was nevertheless involved in some of the more closed intellectual movements of his day. She argues that Bacon’s movement for the advancement of learning was closely connected with the German Rosicrucian movement, while Bacon’s New Atlantis portrays a land ruled by Rosicrucians. He apparently saw his own movement for the advancement of learning to be in conformity with Rosicrucian ideals.[98]

The link between Bacon’s work and the Rosicrucians’ ideals which Yates allegedly found was the conformity of the purposes expressed by the Rosicrucian Manifestos and Bacon’s plan of a “Great Instauration“,[98] for the two were calling for a reformation of both “divine and human understanding”,[c][99], as well as both, had in view the purpose of mankind’s return to the “state before the Fall”.[d][e]

Another major link is said to be the resemblance between Bacon’s New Atlantis and the German Rosicrucian Johann Valentin Andreae‘s Description of the Republic of Christianopolis (1619).[100] Andreae describes a utopic island in which Christian theosophy and applied science ruled, and in which the spiritual fulfilment and intellectual activity constituted the primary goals of each individual, the scientific pursuits being the highest intellectual calling—linked to the achievement of spiritual perfection. Andreae’s island also depicts a great advancement in technology, with many industries separated in different zones which supplied the population’s needs—which shows great resemblance to Bacon’s scientific methods and purposes.[101][102]

While rejecting occult conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and the claim Bacon personally identified as a Rosicrucian, intellectual historian Paolo Rossi has argued for an occult influence on Bacon’s scientific and religious writing. He argues that Bacon was familiar with early modern alchemical texts and that Bacon’s ideas about the application of science had roots in Renaissance magical ideas about science and magic facilitating humanity’s domination of nature.[103] Rossi further interprets Bacon’s search for hidden meanings in myth and fables in such texts as The Wisdom of the Ancients as succeeding earlier occultist and Neoplatonic attempts to locate hidden wisdom in pre-Christian myths.[104] As indicated by the title of his study, however, Rossi claims Bacon ultimately rejected the philosophical foundations of occultism as he came to develop a form of modern science.[103]

Rossi’s analysis and claims have been extended by Jason Josephson-Storm in his study, The Myth of Disenchantment. Josephson-Storm also rejects conspiracy theories surrounding Bacon and does not make the claim that Bacon was an active Rosicrucian. However, he argues that Bacon’s “rejection” of magic actually constituted an attempt to purify magic of Catholic, demonic, and esoteric influences and to establish magic as a field of study and application paralleling Bacon’s vision of science. Furthermore, Josephson-Storm argues that Bacon drew on magical ideas when developing his experimental method.[105] Josephson-Storm finds evidence that Bacon considered nature a living entity, populated by spirits, and argues Bacon’s views on the human domination and application of nature actually depend on his spiritualism and personification of nature.[106]

The Rosicrucian organization AMORC claims that Bacon was the “Imperator” (leader) of the Rosicrucian Order in both England and the European continent, and would have directed it during his lifetime.[107]

Bacon’s influence can also be seen on a variety of religious and spiritual authors, and on groups that have utilized his writings in their own belief systems.[108][109][110][111][112]

Bibliography[edit]

Main article: Francis Bacon bibliography

See also: Essays (Francis Bacon), History of the Reign of King Henry VII, New Atlantis, Novum Organum, Salomon’s House, and The Advancement of Learning

Front page of a 1779 copy of Bacon’s Novum Organum, authored in 1620

Some of the more notable works by Bacon are:

- Essays

- 1st edition with 10 essays (1597)

- 2nd edition with 38 essays (1612)

- 3rd/final edition with 58 essays (1625)

- The Advancement and Proficience of Learning Divine and Human (1605)

- Instauratio magna (The Great Instauration) (1620) – a multi-part work including Distributio operis (Plan of the Work); Novum Organum (The New Organon); Parasceve ad historiam naturalem (Preparatory for Natural History) and Catalogus historiarum particularium (Catalogue of Particular Histories)[113]

- De augmentis scientiarum (1623) – an enlargement of The Advancement of Learning translated into Latin

- New Atlantis (1626)

See also[edit]

- Cestui que (defence and comment on Chudleigh’s Case)

- Romanticism and Bacon

- Scientia potentia est

- Works by Francis Bacon

Notes[edit]

- ^ There is confusion over the spelling of Bacon’s title. Some sources, such as the 2007 Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and the 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, spell it “St. Alban”;[1][2] others, such as the Dictionary of National Biography (1885) and the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, spell the title “St. Albans”.[3][4]

- ^ Contemporary spelling, used by Bacon himself in his letter of thanks to the king for his elevation.[10]

- ^ “Howbeit we know after a time there wil now be a general reformation, both of divine and humane things, according to our desire, and the expectation of others: for it’s fitting, that before the rising of the Sun, there should appear and break forth Aurora, or some clearness, or divine light in the sky” – Fama Fraternitatis (sacred-texts.com Archived 14 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ “Like good and faithful guardians, we may yield up their fortune to mankind upon the emancipation and majority of their understanding, from which must necessarily follow an improvement of their estate […]. For man, by the fall, fell at the same time from his state of innocency and from his dominion over creation. Both of these losses however can even in this life be in some part repaired; the former by religion and faith, the latter by arts and sciences. – Francis Bacon, Novum Organum

- ^ “We ought therefore here to observe well, and make it known unto everyone, that God hath certainly and most assuredly concluded to send and grant to the whole world before her end … such a truth, light, life, and glory, as the first man Adam had, which he lost in Paradise, after which his successors were put and driven, with him, to misery. Wherefore there shall cease all servitude, falsehood, lies, and darkness, which by little and little, with the great world’s revolution, was crept into all arts, works, and governments of men, and have darkened most part of them”. – Confessio Fraternitatis

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Peltonen 2007.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Adamson 1878, p. 200.

- ^ Fowler 1885, p. 346.

- ^ Adamson & Mitchell 1911, p. 135.

- ^ “Bacon” Archived 15 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine entry in Collins English Dictionary.

- ^ Klein, Jürgen (2012), “Francis Bacon”, in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2016 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, retrieved 17 January 2020

- ^ “Empiricism: The influence of Francis Bacon, John Locke, and David Hume”. Sweet Briar College. Archived from the original on 8 July 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Murray, Stuart (2009). The library : an illustrated history. Nicholas A. Basbanes, American Library Association. New York, New York. ISBN 978-1-60239-706-4. OCLC 277203534.

- ^ Dobson, Michael (2001). The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. p. 33.

- ^ Birch, Thomas (1763). Letters, Speeches, Charges, Advices, &c of Lord Chancellor Bacon. Vol. 6. London: Andrew Millar. pp. 271–272. OCLC 228676038.

- ^ Scott Wilson, Resting Places: The Burial Sites of More Than 14,000 Famous Persons, 3rd ed.: 2 (Kindle Locations 2105–2106). McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Pollard 1911, p. 816.

- ^ “Bacon, Francis (BCN573F)”. A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ Collins, Arthur (1741). The English Baronetage: Containing a Genealogical and Historical Account of All the English Baronets, Now Existing: Their Descents, Marriages, and Issues; Memorable Actions, Both in War, and Peace; Religious and Charitable Donations; Deaths, Places of Burial and Monumental Inscriptions. Printed for Tho. Wotton at the Three Daggers and Queen’s Head. p. 5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Adamson & Mitchell 1911, p. 136.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stephen Gaukroger (2001). Francis Bacon and the Transformation of Early-Modern Philosophy. Cambridge University Press, p. 46.

- ^ Francis Bacon, The Advancement of Learning, Clarendon Press, 1876, p. ix.

- ^ Spall, JEH (1971). “Francis Bacon’s connections with Marks Manor House”. Romford Record. Romford: Romford and District Historical Society. No. 4: 32–37.

- ^ Ellis, Robert. P. (27 April 2015). Francis Bacon: The Double-Edged Life of the Philosopher and Statesman. McFarland. p. 28.

- ^ “History of Parliament”. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Spedding, James (1861). “The letters and life of Francis Bacon”.

- ^ “Sir Francis Bacon’s Letters, Tracts and Speech relating to Ireland”. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 24 January 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Paul E. J. Hammer (1999). “The Polarisation of Elizabethan Politics: The Political Career of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, 1585–1597”. p. 141. Cambridge University Press

- ^ Gustav Ungerer (1974). “A Spaniard in Elizabethan England: The Correspondence of Antonio Pérez’s Exile, Volume 1”. p. 207. Tamesis Books

- ^ Weir, Alison Elizabeth the Queen Pimlico 1999 p. 414

- ^ Bunten, Alice Chambers. Twickenham Park and Old Richmond Palace and Francis Bacon: Lord Verulam’s Connection with The, 1580–1608. R. Banks. p. 19.

- ^ Holdsworth, W. S. (1938). History of English Law. pp. vi 473–474.

- ^ Patent Rolls, 2 Jac I p. 12 m 10.

- ^ Longueville, Thomas (1909). The Curious Case of Lady Purbeck; A Scandal of the XVIIth Century. London: Longmans, Green and Co. p. 4.

- ^ Aughterson, Kate. “Hatton, Elizabeth, Lady Hatton [nee Lady Elizabeth Cecil] (1578–1646)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography – via Oxford University Press.

- ^ Adamson & Mitchell 1911, p. 137.

- ^ Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc. 2008. p. 636.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Nieves Matthews, Francis Bacon: The History of a Character Assassination (Yale University Press, 1996)

- ^ Adamson & Mitchell 1911, p. 138.

- ^ Matthews (1996: 56–57)

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rawley, William (1670). The Life of the Right Honorable Francis Bacon Baron of Verulam, Viscount ST. Alban. London: Thomas Johns. Archived from the original on 5 August 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2012.

- ^ Adamson & Mitchell 1911, p. 139.

- ^ Lee, Sidney (1895). “Peachem, Edmond”. The Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 44. Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Ousby, Ian (1996), The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Literature in English, Cambridge University Press, p. 22, ISBN 978-0-521-43627-4.

- ^ Zagorin, Perez (1999), Francis Bacon, Princeton University Press, p. 22, ISBN 978-0-691-00966-7.

- ^ Parris, Matthew; Maguire, Kevin (2004). “Francis Bacon – 1621”. Great Parliamentary Scandals. London: Chrysalis. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-1-86105-736-5.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Zagorin, Perez (1999). Francis Bacon. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-691-00966-7.

- ^ Campbell, John; Baron Campbell (1818), J. Murray. “The Lives of the Lord Chancellors and Keepers of the Great Seal of England“

- ^ Fowler 1885, p. 347.

- ^ Express, Britain. “The Duke of Buckingham and Sir Francis Bacon”. Britain Express. Retrieved 31 October 2022.

- ^ A. L. Rowse, quoted in Parris; Maguire (2004: 8): “a charge of sodomy was… to be brought against the sixty-year-old Lord Chancellor”.

- ^ Montagu, Basil (1837). Essays and Selections. pp. 325–326. ISBN 978-1-4368-3777-4.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1625). The Essayes Or Covnsels, Civill and Morall, of Francis Lo. Vervlam, Viscovnt St. Alban. London. p. 90. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ Josephson-Storm 2017, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1909–1914). [Bartelby.com Essays, Civil and Moral. The Harvard Classics] (Vol III.Part 1 ed.). New York: PF Collier and Son.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Jump up to:a b Alfred Dodd, Francis Bacon’s Personal Life Story’, Volume 2 – The Age of James, England: Rider & Co., 1949, 1986. pp. 157–158, 425, 502–503, 518–532

- ^ Alice Chambers Bunten, Life of Alice Barnham, Wife of Sir Francis Bacon, London: Oliphants Ltd. 1928.

- ^ A. L. Rowse, Homosexuals in History, New York: Carroll & Garf, 1977. p. 44

- ^ Jardine, Lisa; Stewart, Alan Hostage To Fortune: The Troubled Life of Francis Bacon Hill & Wang, 1999. p. 148

- ^ Charles R. Forker, “‘Masculine Love’, Renaissance Writing, and the ‘New Invention’ of Homosexuality: An Addendum” in the Journal of Homosexuality (1996), Indiana University

- ^ Journal of Homosexuality, Volume: 31 Issue: 3, 1996, pp. 85–93, ISSN 0091-8369

- ^ Oliver Lawson Dick, ed. Aubrey’s Brief Lives. Edited from the Original Manuscripts, 1949, s.v. “Francis Bacon, Viscount of St. Albans” p. 11.

- ^ Fulton Anderson, Francis Bacon: His career and his thought, Los Angeles, 1962

- ^ du Maurier, Daphne (1975). Golden Lads: A Study of Anthony Bacon, Francis and Their Friends. London: Gollancz. ISBN 978-1-84408-073-1.

- ^ Aldrich, Robert; Wotherspoon, Gary (2005). Who’s Who in Gay and Lesbian History Vol.1: From Antiquity to the Mid-Twentieth Century. London and New York: Routledge. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-415-15982-1.

- ^ Ross Jackson, The Companion to Shaker of the Speare: The Francis Bacon Story, England: Book Guild Publishing, 2005. pp. 45–46

- ^ Jump up to:a b Bryan Bevan, The Real Francis Bacon, England: Centaur Press, 1960

- ^ Helen Veale, Son of England, India: Indo Polish Library, 1950

- ^ Peter Dawkins, Dedication to the Light, England: Francis Bacon Research Trust, 1984

- ^ Bacon, Francis. The New Atlantis. 1627

- ^ Jump up to:a b The Broadview Anthology of Seventeenth-Century Prose. Broadview Press. 21 March 2001. p. 18.

- ^ Bowen, Catherine (1 January 1993). Francis Bacon: The Temper of a Man. Fordham University Press. p. 225.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1825–1834). Montagu, Basil (ed.). The works of Francis Bacon, lord chancellor of England. Vol. 12. London: W. Pickering. p. 274.

- ^ Rawley, William (Bacon’s personal secretary and chaplain) (1657), Resuscitatio, or, Bringing into Publick Light Several Pieces of the Works, Civil, Historical, Philosophical, & Theological, Hitherto Sleeping; of the Right Honourable Francis Bacon. …Together with his Lordship’s Life,

Francis Bacon, the glory of his age and nation, the adorner and ornament of learning, was born in York House, or York Place, in the Strand, on the two and twentieth day of January, in the year of our Lord 1560.

- ^ Gundry, W.G.C. (ed.), Manes Verulamani This important volume consists of 32 eulogies originally published in Latin shortly after Bacon’s funeral in 1626. Bacon’s peers refer to him as “a supreme poet” and “a concealed poet”, and also link him with the theatre.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lovejoy, Benjamin (1888). Francis Bacon: A Critical Review. London: Unwin. p. 171. OCLC 79886184.

- ^ Officer, Lawrence; Williamson, Samuel. “Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present”. Measuring Worth. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ Turner, Henry S. (2013). “Francis Bacon’s Common Notion”. Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 13 (3): 7–32. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0023. ISSN 1553-3786. S2CID 153693271.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1902). Devey, Joseph (ed.). Novum Organum. New York: Collier. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.17510.

- ^ Brooks, Christopher (1993). “Daniel R. Coquillette. Francis Bacon. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. 1992. Pp. x, 358. $39.50”. Albion. 25 (3): 484–485. doi:10.2307/4050890. ISSN 0095-1390. JSTOR 4050890.

- ^ Nisbet, H. B. (1967). “Herder and Francis Bacon”. The Modern Language Review. 62 (2): 267–283. doi:10.2307/3723840. ISSN 0026-7937. JSTOR 3723840.

- ^ Martin, Julian (1992). Francis Bacon: The State and the Reform of Natural Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38249-6.[page needed]

- ^ Steel, Byron (1930). “Sir Francis Bacon: The First Modern Mind”. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran & Co.

- ^ Hundert, EJ. (1987), “Enlightenment and the decay of common sense.” In: Frits van Holthoon & David R. Olson (Eds.), Common Sense: The Foundations for Social Science (pp. 133–154). Lanham, MD: University Press of America. p. 136.

- ^ Urbach, Peter (1987). Francis Bacon’s Philosophy of Science: An Account and a Reappraisal. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court Publishing Co. ISBN 978-0-912050-44-7. p. 192. “Bacon’s celebrity as a philosopher of science has sunk since the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, when he earned the title of ‘Father of Experimental Philosophy'”.

- ^ Bacon, Francis (1 June 2003). History of Life and Death. ISBN 978-0-7661-6272-3.

- ^ Hepworth Dixon, William (1862). “The story of Lord Bacon’s Life” (1862).

- ^ “Lab” (law). 4. NF, CA: Heritage. 1701. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013.

- ^ Bacon, Locke, and Newton. “The Letters of Thomas Jefferson: 1743–1826”. Netherlands: RUG. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

Bacon, Locke and Newton, whose pictures I will trouble you to have copied for me: and as I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical & Moral sciences

- ^ “FB life” (essay). UK: FBRT. Archived from the original on 31 January 2012.

- ^ Hepworth Dixon, William (1 February 2003). Personal History of Lord Bacon from Unpublished Papers. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-7661-2798-2.

- ^ Crowther, J. G. (19 January 1961). “Article about Francis Bacon”. New Scientist.

- ^ Hepworth Dixon, William (1861). Personal history of Lord Bacon: From unpublished papers. J. Murray. p. 35.

- ^ Wheeler, Harvey. Francis Bacon’s ‘Verulamium’: the Common Law Template of The Modern in English Science and Culture

- ^ Kocher, Paul (1957). “Francis Bacon and the Science of Jurisprudence”. Journal of the History of Ideas. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. 8 (1): 3–26. doi:10.2307/2707577. JSTOR 2707577.

- ^ “Sir Francis Bacon” Archived 2 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. GraysInn.org. Retrieved 21 August 2015

- ^ Hanson, Elizabeth (Spring 1991). “Torture and Truth in Renaissance England”. Representations. 34: 53–84. doi:10.1525/rep.1991.34.1.99p0046u.

- ^ Langbein, John H. (1976). Torture and the Law of Proof. The University of Chicago Press. p. 90.

- ^ Dobson, Michael (2001). The Oxford Companion to Shakespeare. Oxford University Press. p. 33.

- ^ Frances Yates, Theatre of the World, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1969

- ^ Daphne du Maurier, The Winding Stair, Biography of Bacon 1976.

- ^ Frances Yates, The Occult Philosophy in the Elizabethan Age, pp. 61–68, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1979

- ^ Jump up to:a b Frances Yates, The Rosicrucian Enlightenment, London and Boston: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972

- ^ Bacon, Francis. Of the Proficience and Advancement of Learning, Divine and Human

- ^ Andreae 1619.

- ^ Farrington, Benjamin (1951). Francis Bacon, philosopher of industrial science. New York. ISBN 978-0-374-92706-6.

- ^ “Literary criticism of Johann Valentin Andreae”. Enotes.com. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rossi 1968, Chapter 1.

- ^ Rossi 1968, Chapter 3.

- ^ Josephson-Storm 2017, p. 46.

- ^ Josephson-Storm 2017, pp. 50–51.

- ^ “The Mastery of Life” (PDF). Rosicrucian.org. p. 31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 February 2004. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Saint Germain Foundation. The History of the “I AM” Activity and Saint Germain Foundation. Schaumburg, Illinois: Saint Germain Press 2003

- ^ Luk, A.D.K.. Law of Life – Book II. Pueblo, Colorado: A.D. K. Luk Publications 1989, pp. 254–267

- ^ White Paper – Wesak World Congress 2002. Acropolis Sophia Books & Works 2003.

- ^ Partridge, Christopher ed. New Religions: A Guide: New Religious Movements, Sects and Alternative Spiritualities Oxford University Press, United States 2004.

- ^ Schroeder, Werner Ascended Masters and Their Retreats Ascended Master Teaching Foundation 2004, pp. 250–255

- ^ Alban, Francis Bacon, Viscount St (1 January 1620), “Instauratio magna preliminaries”, in Rees (ed.), The Oxford Francis Bacon, Vol. 11: The Instauratio magna Part II: Novum organum and Associated Texts, Oxford University Press, pp. 2–495, doi:10.1093/oseo/instance.00007240, ISBN 978-0-19-924792-9

Sources[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

- Bacon, Francis. The Essays and Counsels, Civil and Moral of Francis Bacon: all 3 volumes in a single file. B&R Samizdat Express, 2014.

- Andreae, Johann Valentin (1619). “Christianopolis”. Description of the Republic of Christianopolis. New York, Oxford university press, American branch; [etc., etc.]

- Spedding, James; Ellis, Robert Leslie; Heath, Douglas Denon (1857–1874). The Works of Francis Bacon, Baron of Verulam, Viscount St Albans and Lord High Chancellor of England (15 volumes). London.

Secondary sources[edit]

- Adamson, Robert (1878), “Francis Bacon” , Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), pp. 200–218

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Adamson, Robert; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911), “Bacon, Francis“, Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), pp. 135–152

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Adamson, Robert; Mitchell, John Malcolm (1911), “Bacon, Francis“, Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (11th ed.), pp. 135–152 This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). “Burghley, William Cecil, Baron“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). pp. 816–817.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Pollard, Albert Frederick (1911). “Burghley, William Cecil, Baron“. Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). pp. 816–817. This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1908). “Bacon, Francis”. New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1908). “Bacon, Francis”. New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. 2 (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.- Crease, Robert P. (2019). “One: Francis Bacon’s New Atlantis”. The Workshop and the World: What Ten Thinkers Can Teach Us About Science and Authority. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-29244-2.

- Fowler, Thomas (1885). “Bacon, Francis (1561–1626)” . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 2. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 328–360.

- Peltonen, Markku (2007) [2004]. “Bacon, Francis, Viscount St Alban (1561–1626)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/990. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading[edit]

- Agassi, Joseph (2013). The Very Idea of Modern Science: Francis Bacon and Robert Boyle. Springer. ISBN 978-94-007-5350-1.

- Farrell, John (2006). “6: The Science of Suspicion”. Paranoia and Modernity: Cervantes to Rousseau. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-7406-4.

- Farrington, Benjamin (1964). The Philosophy of Francis Bacon. University of Chicago Press. Contains English translations of

- Temporis Partus Masculus

- Cogitata et Visa

- Redargutio Philosophiarum

- Josephson-Storm, Jason (2017). The Myth of Disenchantment: Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-40336-6.

- Heese, Mary (1968). “Francis Bacon’s Philosophy of Science”. In Vickers, Brian (ed.). Essential Articles for the Study of Francis Bacon. Hamden, CT: Archon Books. pp. 114–139. ISBN 9780208006240.

- Lewis, Rhodri (2014). “Francis Bacon and Ingenuity”. Renaissance Quarterly. 67 (1): 113–163. doi:10.1086/676154. JSTOR 10.1086/676154. S2CID 170420555.

- Roselle, Daniel; Young, Anne P. “5: The ‘Scientific Revolution’ and the ‘Intellectual Revolution'”. Our Western Heritage.[full citation needed]

- Rossi, Paolo (1968). Francis Bacon: from Magic to Science. University of Chicago Press.

- Serjeantson, Richard. “Francis Bacon and the ‘Interpretation of Nature’ in the Late Renaissance,” Isis (December 2014) 105#4 pp. 681–705.

External links[edit]

Francis Baconat Wikipedia’s sister projects

Media from Commons

Media from Commons Quotations from Wikiquote

Quotations from Wikiquote Texts from Wikisource

Texts from Wikisource Data from Wikidata

Data from Wikidata

- Klein, Juergen. “Francis Bacon”. In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- “Francis Bacon”. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Works by Francis Bacon at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Francis Bacon at Internet Archive

- Works by Francis Bacon at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- “Archival material relating to Francis Bacon”. UK National Archives.

- Contains the New Organon, slightly modified for easier reading

- Lord Macaulay‘s essay Lord Bacon (Edinburgh Review, 1837) [1]

- Francis Bacon of Verulam. Realistic Philosophy and its Age by Kuno Fischer, translated from the German by John Oxenford London 1857

- Bacon by Thomas Fowler (1881) public domain at Internet Archive

- The Francis Bacon Society

- Six Degrees of Francis Bacon

- Journals of the Francis Bacon Society from 1886 to 1999

- English translation of Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s fictional The Lord Chandos Letter, addressed to Bacon

- The George Fabyan Collection at the Library of Congress is rich in the works of Francis Bacon.

- Francis Bacon Research Trust

- Sir Francis Bacon’s New Advancement of Learning

- Montmorency, James E. G. (1913). “Francis Bacon”. In Macdonell, John; Manson, Edward William Donoghue (eds.). Great Jurists of the World. London: John Murray. pp. 144–168. Retrieved 11 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.

- Letterbook and correspondence by Sir Francis Bacon at Columbia University. Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

| hidevteAge of Enlightenment |

|---|

| showTopics |

| showThinkers |

| Romanticism → |

| hideAuthority control | |

|---|---|

| General | ISNI 1VIAF 1WorldCat |

| National libraries | NorwayChileSpainFrance (data)ArgentinaCataloniaGermanyItalyIsraelUnited StatesLatviaJapanCzech RepublicAustraliaGreeceKoreaCroatiaNetherlandsPolandSwedenVatican |

| Art research institutes | RKD Artists (Netherlands)Artist Names (Getty) |

| Biographical dictionaries | Germany |

| Scientific databases | CiNii (Japan)zbMATH |

| Other | FASTMusicBrainz artistRISM (France) 1RERO (Switzerland) 12Social Networks and Archival ContextSUDOC (France) 1Trove (Australia) 1 |

- Lord Chancellors

- Francis Bacon

- Bacon family

- 1561 births

- 1626 deaths

- 16th-century English lawyers

- 16th-century English novelists

- 16th-century English writers

- 16th-century Latin-language writers

- 16th-century male writers

- 16th-century English philosophers

- 16th-century spies

- 17th-century English lawyers

- 17th-century English novelists

- 17th-century English writers

- 17th-century Latin-language writers

- 17th-century English male writers

- 17th-century English philosophers

- 17th-century spies

- Age of Enlightenment

- Alumni of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Atomists

- Attorneys General for England and Wales

- Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship

- British King’s Counsel

- Burials at St Albans

- Christian philosophers

- Christian writers

- Deaths from pneumonia in England

- Empiricists

- English Anglicans

- English essayists

- English legal writers

- English MPs 1572–1583

- English MPs 1584–1585

- English MPs 1586–1587

- English MPs 1589

- English MPs 1593

- English MPs 1597–1598

- English MPs 1601

- English MPs 1604–1611

- English MPs 1614

- English rhetoricians

- English spies

- Epistemologists

- Knights Bachelor

- Logicians

- Lord chancellors of England

- Members of Gray’s Inn

- Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Ipswich

- Members of the Parliament of England (pre-1707) for Liverpool

- Members of the pre-1707 Parliament of England for the University of Cambridge

- Members of the Privy Council of England

- Metaphysicians

- Moral philosophers

- Natural philosophers

- Ontologists

- Peers of England created by James I

- People from St Albans

- People from Westminster

- People of the Elizabethan era

- Philosophers of culture

- Philosophers of ethics and morality

- Philosophers of history

- Philosophers of law

- Philosophers of logic

- Philosophers of mind

- Philosophers of religion

- Philosophers of science

- Philosophers of technology

- 17th-century King’s Counsel

- Authors of utopian literature

- Viscounts in the Peerage of England

- Writers about religion and science

Bacon’s Royal Parentage

(references prepared by Francis Carr & Lawrence Gerald)

https://sirbacon.org/links/parentage.htm

I see you withdraw your favour from me, and now I have lost many friends for your sake: I shall lose you, too. You have put me like one of those that the Frenchmen call Enfans perdu…(lost children); so have you put me into matters of envy without Place or Strength.- Francis Bacon to Queen Elizabeth, “Apologia”

You are my own son, but you, though truly royal, of fresh and masterly spirit shall rule nor England nor your mother, nor reign o’er subjects yet to be. –1577, Queen Elizabeth I in an angry tone to a 16 year old Francis right after she reveals to Francis the secret of his parentage

The fact of Francis Bacon’s Parentage–the legitimate son of Queen Elizabeth and therefore the legal heir to the Throne—is indubitable, supported as it is , not only by a mass of circumstantial evidence but by such direct testimony as Leicester’s letter to King Philip of Spain, which Mme Deventer von Kunow discovered among the Spanish State Archives, begging King Philip to use his influence with Queen Elizabeth to secure his public acknowledgment as Prince Consort……..No one can possibly follow Mme D. von Kunow’s revelations and remain unconvinced.–Williard Parker in the Foreword to Francis Bacon, Last of the Tudors

The 1895 edition of British “Dictionary of National Biography” Vol.16 p114 under the heading “Dudley” :

“Whatever were the Queen’s relations with Dudley before his wife’s death, they became closer after. It was reported that she was formally betrothed to him, and that she had secretly married him in Lord Pembroke’s house, and that she was a mother already.” – January, 1560-1.

“In 1562 the reports that Elizabeth had children by Dudley were revived. One Robert Brooks, of Devizes, was sent to prison for publishing the slander, and seven years later a man named Marsham, of Norwich, was punished for the same offence.”

“When Queen Victoria was staying at Wilton House, the Earl of Pembroke told her that in the muniment room was a document which formed written evidence that in 1560 Elizabeth I married the Earl of Leicester. The marriage was performed in secret oath of absolute secrecy. At the time of that marriage the Queen was pregnant by Lord Leicester. The French and Spanish ambassadors reported this and the death of Amy Robsart to their Courts. They also told the Queen that if this was confirmed by her marriage to Leicester, France and Spain would jointly invade England, to remove the Protestant Queen and replace her by a Catholic monarch. Queen Victoria demanded that this document should be produced, and, after she had examined it, she put it on the fire, saying, “one must not interfere with history.”

This information was given to me by the 15th Earl of Pembroke, the grandfather of the present Earl.- Andrew Lyell

“…..it is not my meaning to treat him {Francis} as a ward: Such a word is far from my Motherly feeling for him. I mean to do him good.” – Lady Anne Bacon in a letter to Anthony Bacon, April 18th, 1593

1. See The Marriage of Elizabeth Tudor by Alfred Dodd

From the writing of Dr. William Rawley, Bacon’s secretary and chaplain:

York House was in the Strand, near the Watergate; York Place was a term used for Whitehall Palace (residence of Queen Elizabeth I). Surely Bacon’s own secretary, chaplain and biographer would know where he was born. But the term, York Place has since been disused and forgotten, so the hint–if that is what it is– it has not been taken up.

2. In the registry of births of St. Martin’s in the Fields Trafalgar Square, for January 26th, 1561, ‘Mr.’ has been interlineated in front of the name of Francis Bacon-added as an afterthought.

3. As a boy, and as a young man, Bacon was always persona grata at Court, although he had no official position and no title. In the Life of Francis Bacon, the first published biography of Bacon by Pierre Amboise, 1631 he writes :

“Francis Bacon saw himself destined one day to hold in his hands

the Helm of the Kingdom. He was born of the Purple.“

4. Francis Bacon bore no resemblance to Sir Nicholas Bacon, but he did look like the Earl of Leicester, as shown in Hilliard’s miniatures.

5. When Nicholas Bacon died, in 1579, he left Francis, his second son, no money in his will. The will is in Somerset House. He assumed that Queen Elizabeth would provide for him instead.

6. Bacon did not go to Nicholas Bacon’s college in Cambridge, Corpus Christi, but to Trinity College, founded by Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth’s father.

7. Through Bacon’s personal letters and circumstances regarding Edward Coke; his long-time rival whose jealousy and malice toward him was based on his knowledge of being the Queen’s son or as Coke publicly slandered him, “the Queen’s bastard.”

8. For five years, from 1580 to 1585, Bacon continually petitioned the Queen and others, regarding his “suit.” Could this be recognition as the Queen’s son? In 1592 he wrote to his uncle Lord Burleigh (William Cecil) :

“My matter is an endless question. Her Majesty has, by set speech, more than once assured me of her intention to call me to her service; which I could not understand out of the place I had been named to. I do confess, primus amour, the first love will not easily be cast off.”

In another letter to Burleigh he wrote:

“I have been like a piece of stuff betoken in a shop.” Coming from a commoner, this would be regarded as gross impertinence. Another complaint was made about the Queen in a letter to Anthony Bacon: ” I receive so little thence, where I deserve the best.”

9. In 1584, at the age of 23, Bacon was made Member of Parliament for Melcombe Regis (Portland), a royal borough. In those days, M.P.’s were not paid. At the same time Bacon had no brief’s, as a barrister. Who paid his fees?

10. In 1593, while still poor, Bacon was given Twickenham Park, a villa with 87 acres of parkland, opposite the Queen’s Palace at Richmond. It was at this house that most of his great works were written.

11. It is accepted that Elizabeth and Leicester were lovers. Immediately on her accession to the throne, she made Leicester Master of the Horse, an important position then, and gave him a bedroom next to hers at Whitehall. They had both been prisoners in the Tower of London in 1554 and 1555. In “Francis Bacon: Last of the Tudors“ by D.von Kunow,( page.11) the Tower chronicle mentions, recording a marriage ceremony between Elizabeth and Leicester conducted by a visiting monk.

12. A.L. Rowse, in “The Elizabethan Renaissance” , vol.1:

“Of course, in the country and abroad, people talked about the Queen’s relations with Leicester. In 1581 Henry Hawkins said that my Lord Robert hath had five children by the Queen, and she never goeth in progress but to be delivered.” Other such references occur in the State Papers.”

Others who went on record as saying that Elizabeth had children by Leicester: Anne Dowe (Imprisoned), Thomas Playfair, who said that Elizabeth had two children, (imprisoned), Robert Gardner (pilloried), and Dionysia Deryck. (pilloried) See All Is Not Gold That Glisters

13. When the Queen came to the throne, the Act of Succession (1563) stated that the Crown after her death would go to the issue of her body “lawfully to be begotten.” Eight years later, in 1571, this phrase was changed, to read “the natural issue of her body.” The words; lawfully to be begotten ; were omitted.

Bacon’s writing : In Happie Memorie of Elizabeth, Queen of England gives testimony to his and the Earl of Essex’s concealed Tudor identites.

In a letter to Essex, Bacon outlines the best approach for his brother to have with Elizabeth. The future of the Tudor dynasty depended on Essex heeding this advice. See The Two Brothers : Politics of the Royal Succession

14.While studying at Gray’s Inn his fees must have been paid by someone else, as Nicholas Bacon left him penniless in his will knowing that the Queen would take care of him.