Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Duchess of Bedford, mother of Elizabeth Woodville (15th GGM)

1415–1472

BIRTH 1415 • Luxembourg

DEATH 30 MAY 1472 • (age 55 – 57)15th great-grandmother

Jacquetta of Luxembourg

Jacquetta of Luxembourg, Countess Rivers (1415/16 – 30 May 1472) was the eldest daughter of Peter I of Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol, Conversano and Brienne, and his wife Margaret of Baux (Margherita del Balzo of Andria).[1] She was a prominent, though often overlooked, figure in the Wars of the Roses. Through her short-lived first marriage to the Duke of Bedford, brother of King Henry V, she was firmly allied to the House of Lancaster. However, following the emphatic Lancastrian defeat at the Battle of Towton, she and her second husband Richard Woodville sided closely with the House of York. Three years after the battle and the accession of Edward IV of England, Jacquetta’s eldest daughter Elizabeth Woodville married him and became Queen consort of England. Jacquetta bore Woodville 14 children and stood trial on charges of witchcraft, of which she was exonerated.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Jacquetta of Luxembourg | |

|---|---|

| Duchess of Bedford Countess Rivers | |

| Born | 1415/16 |

| Died | 30 May 1472 (aged 55–57) |

| Spouse | John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers |

| Issue | Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England Lewis Woodville Anne Woodville, Countess of Kent Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers Mary Woodville, Countess of Pembroke Jacquetta Woodville John Woodville Richard Woodville, 3rd Earl Rivers Martha Woodville Eleanor Woodville Lionel Woodville Margaret Woodville Edward Woodville, Lord Scales Catherine Woodville, Duchess of Buckingham |

| House | Luxembourg |

| Father | Peter I of Luxembourg |

| Mother | Margaret of Baux |

Contents

- 1Family and ancestry

- 2Early life

- 3First marriage

- 4Second marriage

- 5Wars of the Roses

- 6Witchcraft accusations

- 7Heritage

- 8Children

- 9In fiction

- 10Ancestry

- 11References

- 12Further reading

Family and ancestry

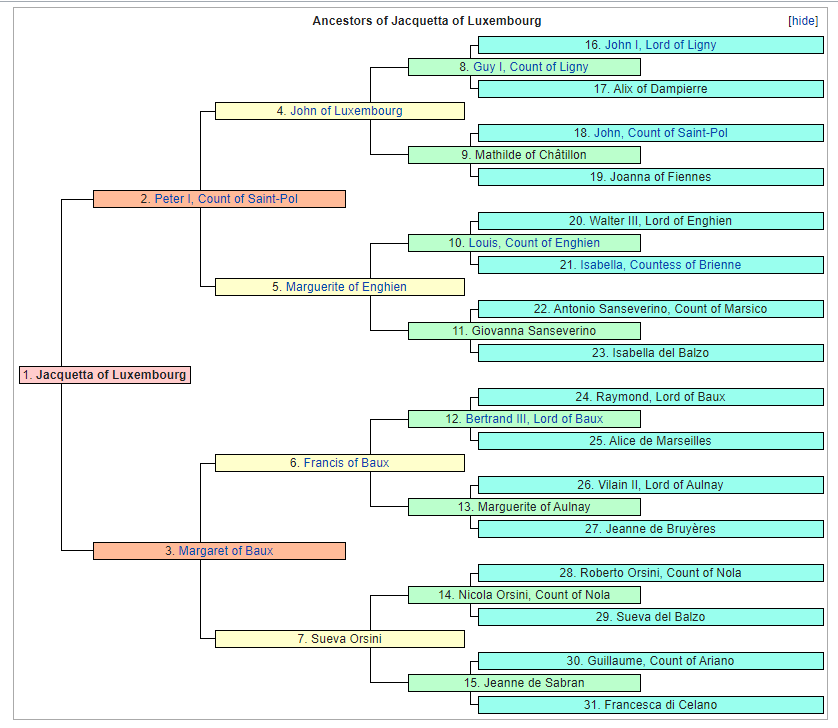

Her father Peter of Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol, was also the hereditary Count of Brienne from 1397 until his death in 1433. Peter had succeeded his father John of Luxembourg, Lord of Beauvoir and mother Marguerite of Enghien, who had been Count and Countess of Brienne from 1394 to her death in 1397. John had been a fourth-generation descendant of Waleran I of Luxembourg, Lord of Ligny, second son of Henry V of Luxembourg and Margaret of Bar. This cadet line of the House of Luxembourg held Ligny-en-Barrois.

Jacquetta’s paternal great-grandmother, Mahaut of Châtillon, was descended from Beatrice of England, daughter of King Henry III of England and Eleanor of Provence.[2] Jacquetta’s mother, Margherita del Balzo, was a daughter of Francesco del Balzo, 1st Duke of Andria, and Sueva Orsini.[3] Sueva descended from Simon de Montfort, 6th Earl of Leicester and Eleanor of England, the youngest child of King John of England and Isabella of Angoulême.[3]

The Luxembourgs claimed legendary descent from the water deity Melusine through their ancestor Siegfried of Luxembourg (c. 922 – 998).[4] Jacquetta was a fourth cousin twice removed of Sigismund of Luxembourg, the reigning Holy Roman Emperor and king of Bohemia and Hungary.

Early life

Jacquetta’s family’s coat of arms

Most of Jacquetta’s early life is a mystery. She was born as the Lancastrian phase of the Hundred Years War began. Her uncle, John II of Luxembourg, Count of Ligny, was the head of the military company that captured Joan of Arc. John held Joan prisoner at Beauvoir and later sold her to the English.

First marriage

On 22 April 1433 at age 17, Jacquetta married John of Lancaster, 1st Duke of Bedford, at Thérouanne. The Duke was the third son of King Henry IV of England and Mary de Bohun, and thus the grandson of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, himself the third son of King Edward III. The marriage was childless and the Duke died on 15 September 1435 at Rouen. As was customary at the time, after her second marriage Jacquetta retained the title of her first husband and was always known as the Duchess of Bedford, this being a higher title than that of countess. Jacquetta inherited one-third of the Duke’s main estates as her widow’s share.[5]

Second marriage

Sir Richard Woodville, son of Sir Richard Woodville who had served as the late Duke’s chamberlain, was commissioned by Henry VI of England to bring Bedford’s young widow to England. During the journey, the couple fell in love and married in secret (before 23 March 1437), without seeking the king’s permission. Jacquetta had been granted dower lands following her first husband’s death on condition that she not remarry without a royal licence. On learning of the marriage, Henry VI refused to see them, but was mollified by the payment of a fine of £1000. The marriage was long and very fruitful: Jacquetta and Richard had fourteen children, including the future Queen Consort Elizabeth Woodville. She lost her first-born son Lewis to a fever when he was 12 years old.

By the mid-1440s, the Woodvilles were in a powerful position. Jacquetta was related to both King Henry and Queen Margaret by marriage. Her sister, Isabelle de Saint Pol, married Margaret’s uncle Charles du Maine while Jacquetta was the widow of Henry VI’s uncle. She outranked all ladies at court with the exception of the queen. As a personal favourite, she also enjoyed special privileges and influence at court. Margaret influenced Henry to create her husband Baron Rivers in 1448, and he was a prominent partisan of the House of Lancaster as the Wars of the Roses began.[4]

Wars of the Roses

The Yorkists crushed the Lancastrians at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461, and Edward IV, the first king from the House of York, took the throne. The husband of Jacquetta’s oldest daughter Elizabeth, Sir John Grey, had been killed a month before at the Second Battle of St. Albans, a Lancastrian victory under the command of Margaret of Anjou. At Towton, however, the tables turned in favour of the Yorkists.

Edward IV met and soon married the widowed Elizabeth Woodville in secret; though the date is not accepted as exactly accurate, it is traditionally said to have taken place (with only Jacquetta and two ladies in attendance) at the Woodville family home in Northamptonshire on 1 May 1464.[6] Elizabeth was crowned queen on 26 May 1465. The marriage, once revealed, ruined the plans of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, Edward’s cousin, who had been negotiating a much-needed alliance with France via a political marriage for Edward.

With Elizabeth now Queen of England, the Woodvilles rose to great prominence and power. Jacquetta’s husband Richard was created Earl Rivers and appointed Lord High Treasurer in March 1466. Jacquetta found rich and influential spouses for her children and helped her grandchildren achieve high posts.[7] She arranged for her 20-year-old son, John, to marry the widowed and very rich Katherine Neville, Duchess of Norfolk, who was at least 45 years older than John. The rise of the Woodvilles created widespread hostility among the Yorkists, including Warwick and the king’s brothers George and Richard, who were being displaced in the king’s favor by the former Lancastrians.

In 1469, Warwick openly broke with Edward IV and temporarily deposed him. Earl Rivers and his son John were captured and executed by Warwick on 12 August at Kenilworth. Jacquetta survived her husband by three years and died in 1472, at about 56 years of age.

Witchcraft accusations

Shortly after her husband’s execution by Warwick, Thomas Wake, a follower of Warwick’s, accused Jacquetta of witchcraft. Wake brought to Warwick Castle a lead image “made like a man-of-arms . . . broken in the middle and made fast with a wire,” and alleged that Jacquetta had fashioned it to use for witchcraft and sorcery. He claimed that the lead image had been found by “an honest person” Harry Kyngeston of Stoke Bruerne, Northamptonshire, in his house after the departure of soldiers, who delivered it to the parish clerk John Daunger of Shutlanger (in the parish of Stoke Bruerne).

Daunger could allegedly attest that Jacquetta had made two other images, one for the king and one for the queen. The case fell apart when Warwick released Edward IV from custody, and Jacquetta was cleared by the king’s great council of the charges on 21 February 1470.[8] In 1484 Richard III in the act known as Titulus Regius[9] revived the allegations of witchcraft against the dead Jacquetta when he claimed that she and Elizabeth had procured Elizabeth’s marriage to Edward IV through witchcraft; however, Richard never offered any proof to support his assertions.

Heritage

Through her daughter Elizabeth, Jacquetta was the maternal grandmother of Elizabeth of York, wife and queen of Henry VII, and therefore an ancestor of all subsequent English monarchs.

Children

- Elizabeth Woodville, Queen consort of England (c. 1437 – 8 June 1492), married first Sir John Grey, second Edward IV of England.

- Lewis Woodville (c. 1438), died in childhood.

- Anne Woodville (1438/9 – 30 July 1489), married first William Bourchier, Viscount Bourchier, second George Grey, 2nd Earl of Kent.

- Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers (c. 1440 – 25 June 1483), married first Elizabeth Scales, 8th Baroness Scales, second Mary Fitzlewis; not married to Gwenllian Stradling, the mother of Margaret.

- John Woodville (c. 1444 – 12 August 1469), married Catherine Neville, Dowager Duchess of Norfolk.

- Jacquetta Woodville (1445–1509), married John le Strange, 8th Baron Strange of Knockin.

- Lionel Woodville, Bishop of Salisbury (c. 1446 – June 1484).

- Eleanor Woodville (d. c. 1512), married Sir Anthony Grey, son of Edmund Grey, 1st Earl of Kent.

- Margaret Woodville (c. 1450 – 1490/1), married Thomas Fitzalan, 17th Earl of Arundel.

- Martha Woodville (d. c. 1500), married Sir John Bromley of Baddington.

- Richard Woodville, 3rd Earl Rivers (1453 – March 1491).

- Edward Woodville, Lord Scales (1454/8 – 28 July 1488).

- Mary Woodville (c. 1456 – 1481), married William Herbert, 2nd Earl of Pembroke.

- Catherine Woodville (c. 1458 – 18 May 1497), married first Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, second Jasper Tudor, Duke of Bedford, and third Sir Richard Wingfield.[10]

Two of Jacquetta’s children are depicted here Anthony and Elizabeth.

The Visitation of Buckinghamshire of 1566 mentions the marriage of William Dormer of Wycombe (only later of Ascott House) to “Agnes, da. of Sir Richard Woodvyle, Erle Ryvers” but does not say whether the father was the first or the third earl, who the mother was or whether Agnes was legitimate.

In fiction

Jacquetta is a main character in Philippa Gregory‘s 2009 novel The White Queen, a fictionalized account of the life of her eldest daughter Elizabeth.[11] In the novel, Jacquetta is portrayed as having indeed dabbled quite a bit in witchcraft, displaying what would seem to be actual power. She is also the main protagonist in Gregory’s 2011 prequel novel The Lady of the Rivers.[12] Gregory’s works explore the historical claim by Jacquetta’s family that they were descended from the water deity Melusine. Gregory uses Jacquetta’s tenuous ties to Melusine and Joan of Arc to further her potential ties to witchcraft. In the 2013 BBC One/Starz television series adaptation The White Queen, Jacquetta is portrayed by actress Janet McTeer.[13]

Jacquetta is also an important character in Margaret Frazer‘s fifth “Player Joliffe” novel, A Play of Treachery (2009). The story is set in 1435–6, after the death of her first husband, John, Duke of Bedford. This historical novel tells a tale regarding her marriage to Sir Richard Woodville. There is no mention of witchcraft in this novel.

Jacquetta is also a prominent character in The Last of the Barons (1843), a novel by Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873). The book’s title is a reference to Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick.

Ancestry

References

| showAncestors of Jacquetta of Luxembourg |

|---|

References

- ^ David Baldwin, Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower, (The History Press, 2010), Genealogical table 4.

- ^ Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study In Colonial And Medieval Families, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 533-542.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Douglas Richardson. Plantagenet Ancestry: A Study In Colonial And Medieval Families, 2nd Edition, 2011. pg 395-402, 538.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Philippa Gregory; David Baldwin; Michael Jones (2011). The Women of the Cousins’ War. London: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Calendar of the Patent Rolls Preserved in the Public Record Office, Volume 3 p. 53 Web. 17 November 2014.

- ^ Robert Fabian, The New Chronicles of England and France, ed. Henry Ellis (London: Rivington, 1811), 654; “Hearne’s Fragment of an Old Chronicle, from 1460–1470,” The Chronicles of the White Rose of York. (London: James Bohn, 1845), 15–16.

- ^ Ralph A. Griffiths, “The Court during the Wars of the Roses”. In Princes Patronage and the Nobility: The Court at the Beginning of the Modern Age, cc. 1450–1650. Edited by Ronald G. Asch and Adolf M. Birke. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-19-920502-7. 59–61.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1467-77, p. 190

- ^ “The Richard III and Yorkist History Server”. r3.org. Archived from the original on 31 August 2008.

- ^ Richard Marius, Thomas More: A Biography, (Harvard University Press, 1984), 119.

- ^ “The White Queen (Official site)”. PhilippaGregory.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ “The Lady of the Rivers (Official site)”. PhilippaGregory.com. Retrieved 7 October 2014.

- ^ “BBC – Media Centre: The White Queen, a new ten-part drama for BBC One”. BBC.co.uk. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

Further reading

- Philippa Gregory; David Baldwin; Michael Jones (2011). The Women of the Cousins’ War. London: Simon & Schuster.

- 1410s births

- 1472 deaths

- 15th-century English people

- 15th-century English women

- 15th-century French people

- 15th-century French women

- English countesses

- English duchesses by marriage

- House of Lancaster

- House of Luxembourg

- Ladies of the Garter

- People acquitted of witchcraft

- People of the Wars of the Roses

- Woodville family

- Witch trials in England

THE LINE OF MELUSINA: JACQUETTA OF LUXEMBOURG

Posted on June 10, 2013 by jasmineamber22

The myth of Melusina.

The myth of Melusina tells the tale of the water goddess Melusina. Melusina was one of three daughters. She was born half fay and half human. When her mother punished her for wrongdoings against her father, Melusina was cursed to become a serpent from the waist down until she met a man who would marry her under the condition of never seeing her on Saturday and keeping his promise. The Luxembourgs claimed their ancestor, Siegfried, married this Goddess. He became enchanted with her when he met her in the forest and asked her hand in marriage, agreeing to not see her on Saturdays under any circumstance. She made their castle of Bock appear the morning after her wedding, as if by magic.

Melusina bore him many children and he kept his promise until one day his father and brothers began teasing him about his wife’s strange behavior. Growing curious, Siegfried went upstairs and opened the door to his wife bathing, seeing that from the waist down her body had been transformed into a serpent’s tale.

Melusina, realizing her husband had broken his promise, departed from him. Upon leaving she said, “But one thing will I say unto thee before I part, that thou, and those who for more than a hundred years shall succeed thee, shall know that whenever I am seen to hover over the fair castle, then will it be certain that in that very year the castle will get a new lord.” Melusina’s cry would haunt her descendants with the tragic news of impending death, and it was from this misery that Jacquetta’s line sprang. Jacquetta would share the magic of her ancestor and would be haunted for life with the sad song of impending death and doom to her house.

A Woman in a Man’s World

Jacquetta of Luxembourg was born in the year 1416 to Peter of Luxembourg and Margaret de Baux. She was their second child. Jacquetta spent her childhood in different castles, unaffected by the war raging on in the kingdom around her. Very little is known about her youth. It is possible that she may have seen Joan of Arc. Jacquetta’s uncle, John of Luxembourg, held Joan of Arc for four months from the English. Though John was tempted to turn her over, his wife, stepdaughter, and great-aunt all claimed that this would send the girl to her death. When John’s great-aunt died however he turned over Joan of Arc and she was burned at the stake for being a witch. Whether or not Jacquetta actually met Joan of Arc, she would have been made aware and seen the consequences for women who rise high in a man’s world.

A Royal Duchess

Jacquetta, like most women of her age, was a pawn in her family’s ambitions. Marriage would be Jacquetta’s destiny. Jacquetta’s groom was John, Duke of Bedford. The Duke had been married previously, to Anne of Burgundy. When his wife died in November 1432, John was deeply grieved and quick to arrange a new marriage. Five months later the Duke was married to seventeen year old Jacquetta, who was twenty-six years younger than her husband. Gaining an old man for a husband had its perks though. Jacquetta, with her new marriage, became the first lady of France, second only to the king’s mother in England.

Jacquetta, after the ceremony, travelled with her husband to Paris. It was in this journey that the war finally came to Jacquetta. On their way the couple was forced to stop in Calais, for the Duke of Bedford had to put down a mutiny. He handled it by executing four of the ringleaders and expelling eighty of the mutinous soldiers. Jacquetta would have no say in these events, but she would begin to understand the tense relationships between France and England and how war worked.

Upon reaching Paris Jacquetta was installed as the lady of the palace of the Hotel de Bourbon. She discovered her husband’s library and his alchemy lab. These luxuries were rare, and through them Jacquetta would be exposed to new religious ideas and the mystical realm. This introduction would later lead to a rumor that would result in grave accusations and actions.

Though Jacquetta would naturally have been curious about her new home she would have very little time to adjust. Two months after her wedding her husband swept her away to England to meet his nephew, the King of England. The king was only twelve years old and his palace was full of intrigue and royal games of power and control. The young Duchess entered to the greetings of the London people. The Duke and Duchess would remain in London for over a year, during which time they would be gifted the Penhurst Place in Kent and news would come of the death of Jacquetta’s father.

After a year the Duke needed to return to France and resume his duties. Jacquetta journeyed back to Paris and returned in 1434 in time for the feast of Christmas. They would not remain here for long.

Country at War

Though England was occupying France, the French were rebelling. French troops were advancing and the French peasants were constantly uprising. The safety of Englishmen in France was no longer guaranteed. In the spring of 1435 the Duke and Jacquetta left for the safer city of Rouen, an English held French city.

The Duke struggled to keep trade routes open and his former ally, and former brother-in-law, The Duke of Burgundy switched allegiance, choosing to no longer aid the English. The Duke was growing weaker and with the loss of his strongest ally he found it difficult to maintain English territories. He installed a new lieutenant, Richard Woodville, in Calais in an attempt to fortify the port.

While the Duke’s health continued to diminish and he began to make his will, Jacquetta grew close to the new captain. The relationship was chaste at this time, and the Duke made no known objections. When he died, on September 14, 1435, he made his wife his sole heir; leaving her all his lands except one estate, and his famous library. Jacquetta was now nineteen, widowed, and rather well endowed. Despite all this Jacquetta was not a free woman; upon the death of her husband she was now under the control of the King of England. She was granted a widow’s pension in February 1436 on the condition that she did not marry without royal permission. The King, no doubt, had plans to arrange a marriage for the widow, but this would not be the case. Young and in love Jacquetta would make her own future as the King struggled with his country and the English-held capital of Paris fell to the French.

Marrying for Love

There is no official record of the marriage between Sir Richard Woodville and Jacquetta of Luxembourg, however the couple travelled to England and confessed their marriage in late 1436 or early 1437. The couple was forgiven, but Jacquetta was order to pay a fine. The couple was official pardoned in October of 1437, just before the birth of their first child, Elizabeth.

Though they could have stayed at court the couple moved to Grafton in Northhamptonshire. William de la Pole sold his manor of Grafton to Sir Richard as a favor to the young couple and they established house.

The couple was blissful, splitting their time between their country estate and the court. In 1438 Jacquetta gave birth to their first son, Lewis. The joy in his birth would be short lived for Lewis would die in infancy. He was followed however by another child, Anne, born in 1439. Before giving birth to another child Richard and Jacquetta inherited more land in 1441 from the death of Richard Woodville’s father. In 1442 Jacquetta gave birth to another son, Anthony Woodville. She would give birth to ten more children, from 1443 until her last daughter in 1458. Richard and Jacquetta would have eight living daughters and five living sons from their happy marriage.

A New Queen of England

To end the war between France and England a marriage was proposed between the king and the fourteen-year-old Princess Margaret of Anjou in 1444. When an English party went out to honor and receive the princess Jacquetta and Sir Richard were among them. Margaret and Jacquetta became friends immediately and Margaret chose Jacquetta to be one of her chief ladies-in-waiting.

The Woodville’s would benefit greatly from the royal attention paid on them. Jacquetta received many gifts from the Queen, and in May of 1448 Richard was promoted to baron. However the Queen’s favoritism had an effect on her popularity; the people of England believed her an agent of France and her constant meddling in politics would have a negative effect on the royals.

A Country Changing

With the growing unpopularity of the royals many people began to rise up and rebel. The King rode off with an army in May of 1450 to put down the rebels. The rebels led the army into a trap and many men were lucky to escape with their lives. When the King returned he and the Queen waited only a couple of days before fleeing London. Jacquetta, and other royals, prepared for siege in the Tower of London. The rebels held the city for a few days before the people of London turned on them and drove them out. The aristocrats exited the tower and the King and Queen returned to London, but it would not be the end of the fighting.

The English now faced the French Army yet again. Their newest target was the rich lands of Gascony, which England had acquired with Eleanor of Aquitaine. King Henry appointed Richard Woodville as Seneschal of Gascony and Jacquetta went with her husband to Plymouth. While they waited to sail the soldiers grew restless. There was no money to pay them and they were given no orders. They waited for the date of sailing, only for the town of Bordeaux to surrender before the expedition even left port. The loss, though great, was ignored, as the English prepared for another attack. Richard Woodville was ordered to Calais and Jacquetta again went with him.

With all the unhappiness there would be one short moment of peace for the Woodville family. Jacquetta and Richard arranged a marriage for their oldest daughter, Elizabeth. She was to marry Sir John Grey, a Lancaster loyalist. Elizabeth was fifteen and her husband was twenty. For Jacquetta, this was seen as a good match, but it would not override her daughter’s second marriage, which would change history.

The Fisher King

When the English lost the lands around Bordeaux the King was struck. It is said he took a fright, complained of feeling sleepy, and went to bed early. In the morning he did not stir, and slipped into a catatonic state. Queen Margaret was seven months pregnant at this time and chose to conceal the King’s lifeless state. Jacquetta was aware of this development, and been aware of the secret movements of the King. While the news leaked and the people grew worried, Margaret would go into her rooms for her royal confinement. Jacquetta would join her for this time, and await the birth of a new King. On October 13,1453 Margaret gave birth to a son, named Edward, and all Lancaster supports, including Jacquetta, were overjoyed.

Complications were presented though. For a baby to be heir he must be recognized by the King. When the baby was presented to the King and put in his arms the King did not respond. As a result, the baby could not carry the title of Prince of Wales because he had not received formal recognition from the King. The Queen had her son christened anyways and Jacquetta watched as the Queen would fight, unsuccessfully, for power.

A Change

Without a King, England was lost. The privy council decided a leader needed to be put in place. Margaret of Anjou suggested she be made regent, but was refused. Instead, Richard, Duke of York, was made leader, and Margaret, along with her ladies, was ordered to Windsor. Jacquetta was in terrible danger, under house arrest with the queen.

In December of 1454 a miracle happened, the king woke up and was reinstated. Jacquetta and her husband received recognition for their loyalty. With the King back in place power shifted again, and the duke resigned.

After only a few months the king and queen called a council meeting. They excluded Richard, the Duke of York, as well as other Yorkist supporters. The Duke, knowing he was being humiliated, gathered his followers. When the king’s party demanded they lay down their arms the Yorkist refused. Jacquetta stayed with the queen in Westminster during this time while the king moved north. Richard and the King battled it out.

Miles away, the Queen would soon hear the alarming news. The King was defeated. Jacquetta fled with the queen and her two-year old son into the Tower of London to prepare for siege. Jacquetta would remain with the queen for some time, emerging from the tower with her and following her to Windsor Castle, and later to Hertford. Eventually Jacquetta left the queen to attend her daughter, Elizabeth, as she gave birth to her first child.

Jacquetta would continue to be loyal to the Queen as leadership changed hands repeatedly. She endured several sieges and fights between the Lancaster line and the Yorkist. Her own kidnapping would be a changing point for her life.

The Kidnapping and Impending War

Lord Rivers and Jacquetta, along with their seventeen-year-old son Anthony were sent to reinforce the port of Sandwich. Warwick’s captain, who was now part of a war against the King, came with 800 men one morning and landed at Sandwich, marching into the tow. Richard and Jacquetta were awoken and as Richard exited the house he was captured. Jacquetta and Anthony were also seized and the three were bundled on board a ship and taken to Calais. The Yorkist waited until nightfall to bring the family in to avoid the people of Calais protesting against the capture of their former commander. Richard protested fiercely against their capture, calling it treason, and he roused the anger of the Yorkist lords. The Yorkist would insult the Rivers, but they would not be harmed. Jacquetta was sent back to England within a few weeks. The Lord Rivers and Anthony, however, were held prisoners for sixth months.

After the release the Rivers returned to their home at Grafton and remained quiet. There is no record of them in 1460, when large purges of Lancaster loyalists were occurring. The Rivers also stayed within their home when Richard, Duke of York, claimed the throne of England. Though they were not party to the going on at court, it is clear Jacquetta would have known what would come next. Having been friends with Margaret of Anjou for fifteen years Jacquetta was well aware that the queen would not give up her sons claim to the throne.

Margaret made agreements with the Scots and returned to England with an army. Lord Rivers and Anthony joined the army while Jacquetta went to once again serve her mistress. During the battle Richard of York was beheaded and it seemed the war would be over, but his eighteen year old son Edward pressed on in his father’s stead. As the battle pressed on the Lancastrian army held the upper hand. During this battle John Grey, Elizabeth’s husband, perished. However it looked as if the Queen would be triumphant. The Queen was reunited with her husband and the royal party, including Jacquetta, stayed at the Abbey of St. Albans. The royal army looted the city and the people prayed to be rescued by Edward, Duke of York.

The lord mayor, in an attempt to save his city, chose Jacquetta, Anne Neville, and the Lady Scales to represent the city and negotiate with the queen to get an assurance that the Scottish army would not be allowed to loot the city.

Jacquetta and her party negotiated with the citizens of London and then reported back to the Queen. The Queen was unsatisfied and sent the ladies back to have the citizens proclaim Edward of York a traitor. While the Queen sent her ladies she also dispatched two bands of soldiers, confirming the citizens fears. They barred her from the city and Jacquetta left the city. The Londoners now began to raise money for the Yorkist armies. Edward was brought to London a hero and proclaimed King. The Queen retreated back North. Edward won one more major battle, and the Lancaster forces surrendered. Lord Rivers and his sons turned over their swords and accepted a new King.

A New King and Queen

The Rivers were pardoned by the King. He was attempting to befriend and reunite the divided nobility. Anthony, now nineteen, was married off by Jacquetta. While they were overjoyed at one marriage, their daughter, Elizabeth was now struggling. With her husband dead she had two sons to take care of. Though she was meant to receive an income her mother-in-law had no intentions of allowing the young widow to live off of her. Elizabeth went to her parents at Grafton to seek help.

A year later, in the early summer, King Edward made his way north to recruit men. When stopping at Grafton he was met on the road by Elizabeth, who appealed for help in support of her claim for her dowry lands. The King was besotted with the twenty-seven year old widow. The two were married in secret within weeks of first meeting.

With Elizabeth’s rise, Jacquetta rose as well. She now would be the Queen’s mother. Once again Jacquetta was one of the highest ranked women in England. With this rise however, rumors spread. It was said that Jacquetta and Elizabeth trapped the King with witchcraft, and this rumor would haunt both for life. There is no certainty of this, however, whatever power willed the King to marry her daughter, Jacquetta was well aware of the powerful position her family had just been granted. Edward would admit the marriage in September of 1464 to the horror of his councilors.

Jacquetta’s family was overjoyed though. Richard Woodville became Earl Rivers in 1446 and was appointed to the post of Constable of England. Jacquetta used her new position to arrange advantageous marriages for her children, marrying them to heirs and heiresses.

A Brother’s War

Though the cousin’s war was now over, a new war would ignite. The Earl of Warwick was unhappy with Edward’s choice of a wife and married his own daughter to the King’s younger brother, George. Warwick then, with his allies, invaded England against his former ally. The King lost, his first defeat, and knowing his wife’s family would now be in danger sent Richard Woodville and his son John to Grafton where Jacquetta already was. The men then left from there to make their way to Wales.

Father and son were captured by the Earl of Warwick’s men. Sir Richard and his son would be beheaded on the orders of the Earl of Warwick. Grafton was the last time Jacquetta would have seen her husband. Their heads were displayed on the walls of Coventry. Warwick then sent a guard to Grafton and had Jacquetta snatched from her home. He intended to try her as a witch.

There was a formal trial for Jacquetta. If found guilty Jacquetta would be burned at the stake as a witch. Witnesses were called to present testimony of Jacquetta’s unholy practices. The evidence was enough to execute the Duchess. Warwick however, for whatever reason, changed his mind and released Jacquetta. It is possible Warwick feared the retribution that would come if he executed such a well-connected lady. Whatever the reason Jacquetta was freed and she fled to join her daughter at the Tower of London.

Warwick soon found he could not hold the country without a King and Edward was released. He joined his wife, who left the tower, and an agreement was reached. Edward then helped Jacquetta formally clear her name of witchcraft.

A Dreadful Conclusion

Warwick and the King’s peace was short lived and Warwick invaded again. The King fled with Jacquetta’s son Anthony. Jacquetta fled into the safety of Westminster Abbey with her pregnant daughter Elizabeth and Elizabeth’s three young daughters. In Westminster Abbey Jacquetta assisted her daughter in delivering another child, a son and heir to the House of York. Jacquetta and her family remained in the Abbey, where they were safe from arrest. Meanwhile, Edward’s brother George turned on his father-in-law Warwick and joined Edward when the invaded England.

As they paraded successfully through London Jacquetta and her family were liberated, and went to the Tower for safety while Edward took his army to meet the invasion of Margaret of Anjou. Edward was successful again, killing Margaret of Anjou’s son and capturing Margaret, but his success did little to help his own family. While the King was fighting the Lancaster heir, Lancaster supporters attacked the Tower of London. Anthony Woodville returned from battle to protect his mother and sister and led a counterattack that defeated the Lancastrian forces.

Jacquetta saw many things after this battle. Her friend Margaret Anjou became a prisoner of England, and was eventually released to her family. Edward and Elizabeth were restored to their throne. She would live just long enough to see her family returned to glory. Jacquetta died a year later in 1472, leaving behind a legacy of children and an English queen.

Little is written of Jacquetta of Luxembourg but it is clear that she was a forward thinking woman during a regressive time. She was a woman who ventured outside of the traditional role of women and chose to forge her own destiny in the world.

Related

Queen of the NileJune 24, 2015In “History”

Her Holiness, JoanJuly 31, 2015In “History”

Bloody MaryJanuary 15, 2013In “History”

This entry was posted in History and tagged Elizabeth Woodville, England, Jacquetta Woodville, Margaret of Anjou, Melusina, The Cousin’s War, The Rivers. Bookmark the permalink.

← NO GOOD TO THE HOUSE OF NAPLES: MARIA CAROLINA

LADY FÜHRER: HITLER’S MISTRESS →

7 Responses to THE LINE OF MELUSINA: JACQUETTA OF LUXEMBOURG

tudorqueen6says:October 9, 2013 at 5:35 amMight I ask what sources were used for this?Reply

jasmineamber22 says:October 9, 2013 at 10:52 amPrimarily The Women of the Cousins War since from all my research it is the only biography that exist on Jacquetta of Luxembourg. The myth of Melusina was retold using online sources and a book on myths I have.Reply

Yvonne says:May 12, 2014 at 6:03 amGreat Reading Thank you.Reply

- Pingback: [ jacquetta of luxembourg ] Best Web Pages | (KoreanNetizen)

Mary Taylor says:January 16, 2015 at 8:30 pmThank you for a wonderful article.Reply

Dorothy Daviessays:February 10, 2015 at 11:51 amyou did a better job than The Lady Of the Rivers on this outstanding medieval figure. Check out my book on Jacquetta, Not The Shadow of a Man, available online from fiction4all.com

a book on Antony Woodville, KG, Lord Scales of Newcelles and the Isle of Wight, 2nd Earl Rivers, is being written. A book on his brother, Thomas Woodville, outlining his connections with the Isle of Wight (where I live) and the disastrous campaign of 1488 which saw the deaths of 440 islanders, is also available. Captain Of The Wight. I had a plaque placed in Carisbrooke Castle Museum to commemorate the campaign, the men and Sir Thomas, as no one had done that. My research came from the original medieval report of the whole thing which I found in an American magazine dated 1901, the pages had not been cut… that was a wonderful experience, opening up something so old and finding a medieval report!Replyjasmineamber22 says:June 24, 2015 at 8:59 pmI’ll look into your book. I love reading.Reply