Elizabeth Woodville, Queen of England, wife of Edward IV, (14th & 15th GGM) ~ 1437–1492

BIRTH 3 FEBRUARY 1437 • Grafton Regis, South Northamptonshire Borough, Northamptonshire, England

DEATH 8 JUNE 1492 • Bermondsey, London Borough of Southwark, Greater London, England

14th great-grandmother

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Elizabeth Woodville | |

|---|---|

| Queen consort of England | |

| Tenure | 1 May 1464 – 3 October 1470 |

| Coronation | 26 May 1465 Westminster Abbey |

| Tenure | 11 April 1471 – 9 April 1483 |

| Born | c. 1437 Grafton Regis, Northamptonshire, England |

| Died | 8 June 1492 (about 55) Bermondsey, Surrey, England |

| Burial | 12 June 1492 St George’s Chapel |

| Spouse | Sir John Grey (m. c. 1452; died 1461)Edward IV of England(m. 1464; died 1483) |

| Issue among others | Thomas Grey, Marquess of DorsetSir Richard GreyElizabeth, Queen of EnglandEdward V of EnglandRichard, Duke of YorkCatherine, Countess of Devon |

| Father | Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers |

| Mother | Jacquetta of Luxembourg |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Elizabeth Woodville (also spelled Wydville, Wydeville, or Widvile[nb 1]) (c. 1437[1] – 8 June 1492) was Queen of England as the spouse of King Edward IV from 1464 until his death in 1483.

At the time of her birth, her family was of middle rank in the English social hierarchy. Her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, had previously been an aunt-by-marriage to Henry VI. Elizabeth’s first marriage was to a minor supporter of the House of Lancaster, Sir John Grey of Groby. He died at the Second Battle of St Albans, leaving Elizabeth a widowed mother of two sons.

Her second marriage to Edward IV was a cause célèbre of the day, thanks to Elizabeth’s great beauty and lack of great estates. Edward was the first king of England since the Norman Conquest to marry one of his subjects,[2][3] and Elizabeth was the first such consort to be crowned queen.[nb 2] Her marriage greatly enriched her siblings and children, but their advancement incurred the hostility of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, ‘The Kingmaker’, and his various alliances with the most senior figures in the increasingly divided royal family. This hostility turned into open discord between King Edward and Warwick, leading to a battle of wills that finally resulted in Warwick switching allegiance to the Lancastrian cause, and to the execution of Elizabeth’s father, Richard Woodville, in 1469.

Elizabeth-Woodville-Wikipedia

After the death of her husband in 1483, Elizabeth remained politically influential even after her son, briefly proclaimed King Edward V of England, was deposed by her brother-in-law, Richard III. Edward and his younger brother Richard both disappeared soon afterward, and are presumed to have been murdered. Elizabeth subsequently played an important role in securing the accession of Henry VII in 1485. Henry married her daughter Elizabeth of York, ended the Wars of the Roses, and established the Tudor dynasty. Through her daughter, Elizabeth was a grandmother of the future Henry VIII. Elizabeth was forced to yield pre-eminence to Henry VII’s mother, Lady Margaret Beaufort; her influence on events in these years, and her eventual departure from court into retirement, remain obscure.[4][5]

Contents

- 1Early life and first marriage

- 2Queen consort

- 3Queen dowager

- 4Life under Richard III

- 5Life under Henry VII

- 6Issue of Elizabeth Woodville

- 7In literature

- 8Media portrayals

- 9Schools named after Elizabeth Woodville

- 10Arms

- 11Notes

- 12References

- 13Further reading

- 14External links

Early life and first marriage

Elizabeth Woodville was born about 1437, possibly in October,[nb 3][6] at Grafton Regis, Northamptonshire. She was the firstborn child of a socially unequal marriage between Sir Richard Woodville and Jacquetta of Luxembourg, which briefly scandalized the English court. The Woodvilles, though an old and respectable family, were gentry rather than noble, a landed and wealthy family that had previously produced commissioners of the peace, sheriffs, and MPs, rather than peers of the realm; Elizabeth’s mother, in contrast, was the widow of the Duke of Bedford, uncle of King Henry VI of England.

In about 1452, Elizabeth Woodville married Sir John Grey of Groby, the heir to the Barony Ferrers of Groby. He was killed at the Second Battle of St Albans in 1461, fighting for the Lancastrian cause. This would become a source of irony, since Elizabeth’s future husband Edward IV was the Yorkist claimant to the throne. Elizabeth Woodville’s two sons from this first marriage were Thomas (later Marquess of Dorset) and Richard.

Elizabeth Woodville was called “the most beautiful woman in the Island of Britain” with “heavy-lidded eyes like those of a dragon.”[7]

Queen consort

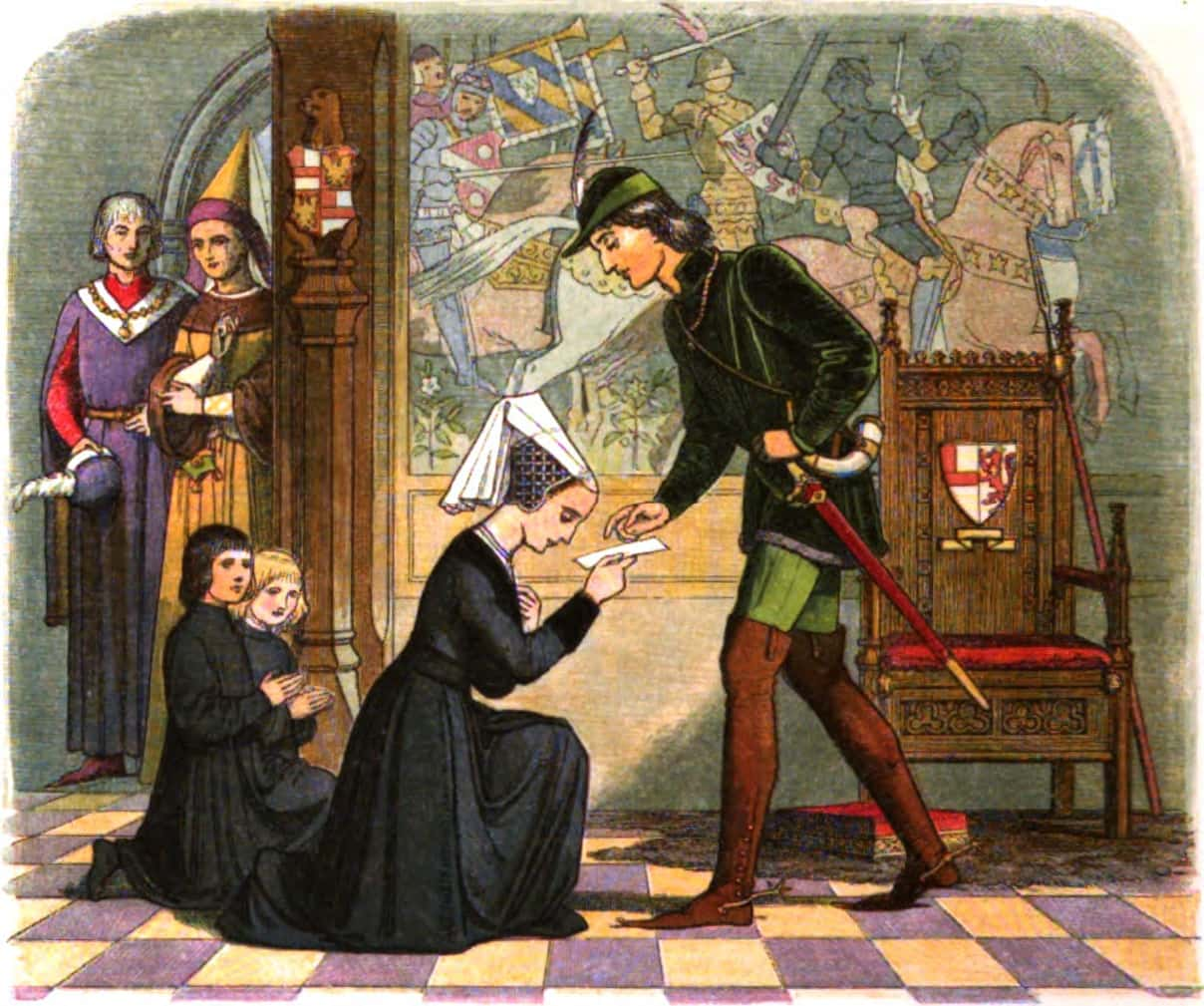

Illuminated miniature depicting the marriage of Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville, Anciennes Chroniques d’Angleterre by Jean de Wavrin, 15th centuryElizabeth as queen, with Edward and their oldest son. From Dictes and Sayings of the Philosophers, Lambeth Palace.

Edward IV had many mistresses, the best known of them being Jane Shore, and he did not have a reputation for fidelity. His marriage to the widowed Elizabeth Woodville took place secretly and, though the date is not known, it is traditionally said to have taken place at her family home in Northamptonshire on 1 May 1464. [8] Only the bride’s mother and two ladies were in attendance. Edward married her just over three years after he had assumed the English throne in the wake of his overwhelming victory over the Lancastrians, at the Battle of Towton, which resulted in the displacement of King Henry VI. Elizabeth Woodville was crowned queen on 26 May 1465, the Sunday after Ascension Day.

In the early years of his reign, Edward IV’s governance of England was dependent upon a small circle of supporters, most notably his cousin, Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick. At around the time of Edward IV’s secret marriage, Warwick was negotiating an alliance with France in an effort to thwart a similar arrangement being made by his sworn enemy Margaret of Anjou, wife of the deposed Henry VI. The plan was that Edward IV should marry a French princess. When his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, who was both a commoner and from a family of Lancastrian supporters became public, Warwick was both embarrassed and offended, and his relationship with Edward IV never recovered. The match was also badly received by the Privy Council, who according to Jean de Waurin told Edward with great frankness that “he must know that she was no wife for a prince such as himself”.

With the arrival on the scene of the new queen came many relatives, some of whom married into the most notable families in England.[9] Three of her sisters married the sons of the earls of Kent, Essex and Pembroke. Another sister, Catherine Woodville, married the queen’s 11-year-old ward Henry Stafford, 2nd Duke of Buckingham, who later joined Edward IV’s brother Richard, Duke of Gloucester, in opposition to the Woodvilles after the death of Edward IV. Elizabeth’s 20-year-old brother John married Katherine, Duchess of Norfolk. The Duchess had been widowed three times and was probably in her sixties, so that the marriage created a scandal at court. Elizabeth’s son from her first marriage, Thomas Grey, married Cecily Bonville, 7th Baroness Harington.

When Elizabeth Woodville’s relatives, especially her brother Anthony Woodville, 2nd Earl Rivers, began to challenge Warwick’s pre-eminence in English political society, Warwick conspired with his son-in-law George, Duke of Clarence, the king’s younger brother. One of his followers accused Elizabeth Woodville’s mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, of practising witchcraft. She was acquitted the following year.[10] Warwick and Clarence twice rose in revolt and then fled to France. Warwick formed an uneasy alliance with the Lancastrian Queen Margaret of Anjou and restored her husband Henry VI to the throne in 1470. But the following year, Edward IV, returned from exile and defeated Warwick at the Battle of Barnet, and the Lancastrians at the Battle of Tewkesbury. Henry VI was killed soon afterwards.

Following her husband’s temporary fall from power, Elizabeth Woodville sought sanctuary in Westminster Abbey, where she gave birth to a son, Edward (later King Edward V of England). Her marriage to Edward IV produced a total of ten children, including another son, Richard, Duke of York, who would later join his brother as one of the Princes in the Tower.[6] Five daughters also lived to adulthood.

Elizabeth Woodville engaged in acts of Christian piety in keeping with conventional expectations of a medieval queen consort. Her acts included making pilgrimages, obtaining a papal indulgence for those who knelt and said the Angelus three times per day, and founding the chapel of St. Erasmus in Westminster Abbey.[11]

Queen dowager

Following Edward IV’s sudden death, possibly from pneumonia, in April 1483, Elizabeth Woodville became queen dowager. Her young son, Edward V, became king, with his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, acting as Lord Protector. In response to the Woodvilles’ attempt to monopolise power, Gloucester quickly moved to take control of the young king and had the king’s uncle Earl Rivers and half-brother Richard Grey, son to Elizabeth, arrested. The young king was transferred to the Tower of London to await the coronation. With her younger son and daughters, Elizabeth again sought sanctuary. Lord Hastings, the late king’s leading supporter in London, initially endorsed Gloucester’s actions, but Gloucester then accused him of conspiring with Elizabeth Woodville against him. Hastings was summarily executed. Whether any such conspiracy really occurred is not known.[12] Richard accused Elizabeth of plotting to “murder and utterly destroy” him.[13]

On 25 June 1483, Gloucester had Elizabeth Woodville’s son Richard Grey and brother Anthony, Earl Rivers, executed in Pontefract Castle, Yorkshire. By an act of Parliament, the Titulus Regius (1 Ric. III), it was declared that Edward IV’s children with Elizabeth were illegitimate on the grounds that Edward IV had a precontract with the widow Lady Eleanor Butler, which was considered a legally binding contract that rendered any other marriage contract invalid. One source, the Burgundian chronicler Philippe de Commines, says that Robert Stillington, Bishop of Bath and Wells, carried out an engagement ceremony between Edward IV and Lady Eleanor.[14] The act also contained charges of witchcraft against Elizabeth, but gave no details and the charges had no further repercussions. As a consequence, the Duke of Gloucester and Lord Protector was offered the throne and became King Richard III. Edward V, who was no longer king, and his brother Richard, Duke of York, remained in the Tower of London. There are no recorded sightings of them after the summer of 1483.

Life under Richard III

Now referred to as Dame Elizabeth Grey,[6] she, with Duke of Buckingham (a former close ally of Richard III and now probably seeking the throne for himself) now allied themselves with Lady Margaret Stanley (née Beaufort) and espoused the cause of Margaret’s son Henry Tudor, a great-great-great-grandson of King Edward III,[15] the closest male heir of the Lancastrian claim to the throne with any degree of validity.[nb 4] To strengthen his claim and unite the two feuding noble houses, Elizabeth Woodville and Margaret Beaufort agreed that the latter’s son should marry the former’s eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, who upon the death of her brothers became the heiress of the House of York. Henry Tudor agreed to this plan and in December 1483 publicly swore an oath to that effect in the cathedral in Rennes, France. A month earlier, an uprising in his favour, led by Buckingham, had been crushed.

Richard III’s first Parliament of January 1484 stripped Elizabeth of all the lands given to her during Edward IV’s reign.[16] On 1 March 1484, Elizabeth and her daughters came out of sanctuary after Richard III publicly swore an oath that her daughters would not be harmed or molested and that they would not be imprisoned in the Tower of London or in any other prison. He also promised to provide them with marriage portions and to marry them to “gentlemen born”. The family returned to Court, apparently reconciled to Richard III. After the death of Richard III’s wife Anne Neville, in March 1485, rumours arose that the newly widowed king was going to marry his beautiful and young niece Elizabeth of York.[17]

Life under Henry VII

In 1485, Henry Tudor invaded England and defeated Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth Field. As King, Henry VII married Elizabeth of York and had the Titulus Regius revoked and all found copies destroyed.[18] Elizabeth Woodville was accorded the title and honours of a queen dowager.[19]

Scholars differ about why Dowager Queen Elizabeth spent the last five years of her life living at Bermondsey Abbey, to which she retired on 12 February 1487. Among her modern biographers, David Baldwin believes that Henry VII forced her retreat from the Court, while Arlene Okerlund presents evidence from July 1486 that she was already planning her retirement from court to live a religious, contemplative life at Bermondsey Abbey.[20] Another suggestion is that her retreat to Bermondsey was forced on her because she was in some way involved in the 1487 Yorkist rebellion of Lambert Simnel, or at least was seen as a potential ally of the rebels.[21]

At Bermondsey Abbey, Elizabeth was treated with the respect due to a dowager queen. She lived a regal life on a pension of £400 and received small gifts from Henry VII.[22] She was present at the birth of her granddaughter Margaret at Westminster Palace in November 1489 and at the birth of her grandson, the future Henry VIII, at Greenwich Palace in June 1491. Her daughter Queen Elizabeth visited her on occasion at Bermondsey, although another one of her other daughters, Cecily of York, visited her more often.

Henry VII briefly contemplated marrying his mother-in-law to King James III of Scotland, when James III’s wife, Margaret of Denmark, died in 1486.[23] However James III was killed in battle in 1488.

Elizabeth Woodville died at Bermondsey Abbey, on 8 June 1492.[6] With the exception of the queen, who was awaiting the birth of her fourth child, and Cecily of York, her daughters attended the funeral at Windsor Castle; Anne of York (the future wife of Thomas Howard), Catherine of York (the future Countess of Devon) and Bridget of York (a nun at Dartford Priory). Elizabeth’s will specified a simple ceremony.[24] The surviving accounts of her funeral on 12 June 1492 suggest that at least one source “clearly felt that a queen’s funeral should have been more splendid” and may have objected that “Henry VII had not been fit to arrange a more queenly funeral for his mother-in-law”, although simplicity was the queen dowager’s own wish.[24] A letter discovered in 2019, written in 1511 by Andrea Badoer, the Venetian ambassador in London, suggests that she had died of plague, which would explain the haste and lack of public ceremony.[25][26] Elizabeth was laid to rest in the same chantry as her husband King Edward IV in St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle.[6]

Issue of Elizabeth Woodville

By Sir John Grey

- Thomas Grey, Earl of Huntingdon, Marquess of Dorset and Lord Ferrers de Groby (1455 – 20 September 1501), married first Anne Holland, but she died young without issue; he married second on 18 July 1474, Cecily Bonville, suo jure Baroness Harington and Bonville, by whom he had fourteen children. The disputed queen Lady Jane Grey is a direct descendant from this line.[27]

- Richard Grey (1457 – 25 June 1483) was executed at Pontefract Castle.

By King Edward IV

- Elizabeth of York (11 February 1466 – 11 February 1503), Queen consort of England as the wife of Henry VII (reigned 1485–1509). Mother of Henry VIII (reigned 1509–1547).

- Mary of York (11 August 1467 – 23 May 1482), buried in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle

- Cecily of York (20 March 1469 – 24 August 1507), Viscountess Welles

- Edward V of England (2 November 1470 – c. 1483), one of the Princes in the Tower

- Margaret of York (10 April 1472 – 11 December 1472), buried in Westminster Abbey

- Richard, Duke of York (17 August 1473 – c. 1483), one of the Princes in the Tower

- Anne of York (2 November 1475 – 23 November 1511), Lady Howard

- George, Duke of Bedford (March 1477 – March 1479), buried in St George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle

- Catherine of York (14 August 1479 – 15 November 1527), Countess of Devon

- Bridget of York (10 November 1480 – 1507), nun at Dartford Priory, KentElizabeth’s daughters by Edward IV

In literature

Elizabeth Woodville is thought to have been the author of one of only three lyric poems in Middle English ascribed to a woman author. A “Hymn to Venus”, found in one single manuscript[28] in which it is ascribed to “Queen Elizabeth”, is a complex six-stanza poem that praises Venus, the goddess of love.[29] It is an “elaboration of the sestina“, in which the first line of each seven-line stanza is also its last line, and the lines of the first stanza provide the first lines for each subsequent stanza.[30]

Non-fiction[edit]

- Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower (2002) by David Baldwin

- Elizabeth Wydeville: The Slandered Queen (2005) by Arlene Okerlund

- The Women of the Cousins’ War (2011) by Philippa Gregory, David Baldwin and Michael Jones. The book deals with Jacquetta of Luxembourg (mother of Elizabeth Woodville) (chapter written by Philippa Gregory), Elizabeth Woodville (chapter written by David Baldwin), and Lady Margaret Beaufort (mother of Elizabeth Woodville’s son-in-law King Henry VII) (chapter written by Michael Jones)

- Elizabeth Woodville (2013) by David MacGibbon

- The Woodvilles: The Wars of the Roses and England’s Most Infamous Family (2013) by Susan Higginbotham

- Edward IV and Elizabeth Woodville: A True Romance (2016) by Amy Licence

Fiction[edit]

Edward IV’s love for his wife is celebrated in sonnet 75 of Philip Sidney‘s Astrophel and Stella.[31] (written by 1586, first pub. 1591).

She appears in two of Shakespeare‘s plays: Henry VI Part 3 (written by 1592), in which she is a fairly minor character, and Richard III (written approx. 1592), where she has a central role. Shakespeare portrays Elizabeth as a proud and alluring woman in Henry VI Part 3. By Richard III, she is careworn from having to defend herself against detractors in the court, including her titular brother-in-law Richard. She is one of Richard’s cleverest opponents, as she sees through him from the beginning, but she is also melodramatic and self-pitying. Although most modern editions of Henry VI Part 3 and Richard III call her “Queen Elizabeth” in the stage directions, the original Shakespearean Folio never actually refer to her by name, instead calling her first “Lady Grey” and later simply “Queen.”

Novels that feature Elizabeth Woodville as a character include:

- The Last of the Barons by Edward Bulwer-Lytton Available online.

- Dickon (1929) by Marjorie Bowen.

- The Daughter of Time (1951), Josephine Tey‘s classic mystery.

- The White Rose (1969) by Jan Westcott.

- The King’s Grey Mare (1972) by Rosemary Hawley Jarman, a fictionalised biography of Elizabeth Woodville.

- The Woodville Wench (published in US as The Queen Who Never Was) (1972) by Maureen Peters.

- The Sunne in Splendour (1982) by Sharon Kay Penman.

- The Sun in Splendour (1982) by Jean Plaidy.

- A Secret Alchemy (2009) by Emma Darwin.

- The White Queen (2009) by Philippa Gregory, which borrows Rosemary Hawley Jarman‘s supernatural elements from The King’s Grey Mare. Elizabeth Woodville also appears in other novels in Gregory’s Cousins’ War series.

- The King’s Grace (2009) by Anne Easter Smith The life of Edward IV’s illegitimate daughter who spent many years in service of the Dowager Queen.

- Das Spiel der Könige, a historical novel in German by Rebecca Gablé.

- Bloodline (2015) and Ravenspur (2016), in the “War of Roses” series by Conn Iggulden

Media portrayals[edit]

Film[edit]

- Richard III (1911): Woodville was played by Violet Farebrother

- Richard III (1912): Woodville was played by Carey Lee.

- In the French film, Les enfants d’Édouard (1914), Woodville was played by Jeanne Delvair.

- Jane Shore (1915): Woodville was played by Maud Yates.

- Tower of London (1939): Woodville was played by Barbara O’Neil.

- Richard III (1955): Woodville was portrayed by Mary Kerridge.

- In the Hungarian TV movie III. Richárd (1973) Woodville was played by Rita Békés.

- Richard III (1995): Woodville was played by Annette Bening.

- Looking For Richard (1996): Woodville was played by Penelope Allen.

- Richard III (2005): Woodville was played by Caroline Burns Cooke.

- Richard III (2008): Woodville was played by María Conchita Alonso.

Television[edit]

- An Age of Kings (1960): Woodville was portrayed by Jane Wenham.

- Wars of the Roses (1965): Woodville was played by Susan Engel.

- The Shadow of the Tower (1972): Woodville was played by Stephanie Bidmead

- The Third Part of Henry the Sixth and The Tragedy of Richard III (1983): Woodville was played by Rowena Cooper.

- The White Queen (2013): Woodville was portrayed by Rebecca Ferguson.

- The Hollow Crown, Henry VI and Richard III (2016): Woodville was played by Keeley Hawes.

- The White Princess (2017): Woodville was played by Essie Davis.

Music[edit]

- In 2020, Vicki Manser portrayed Elizabeth Woodville on the cast recording of A Mother’s War, a musical based on the Wars of the Roses.

Schools named after Elizabeth Woodville[edit]

- Elizabeth Woodville Primary School, Groby, Leicestershire (1971).[32]

- Elizabeth Woodville Secondary School, Roade, Northamptonshire (2011).[33]

Arms[edit]

| EscutcheonElizabeth Woodville’s arms as queen consort, the royal arms of England impaling Woodville (Quarterly, first argent: a lion rampant double queued gules, crowned or (Limburg-Luxembourg, her mother’s family); second: quarterly, I and IV: gules a star of eight points argent; II and III: azure, semée of fleurs de lys or (Baux); third: barry argent and azure, overall a lion rampant gules (Lusignan); fourth: gules, three bendlets argent, on a chief of the first, charged with a fillet in base or, a rose of the second (Orsini); fifth: three pallets vairy, on a chief or a label of five points azure (Châtillon); and sixth, argent a fess and a canton conjoined gules (Woodville))SupportersDexter, a lion argent. Sinister, a greyhound argent collared gules.[34] |

Notes[edit]

- ^ Although spelling of the family name is usually modernised to “Woodville”, it was spelled “Wydeville” in contemporary publications by Caxton, but her tomb at St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Castle is inscribed thus: “Edward IV and his Queen Elizabeth Widvile”.

- ^ John‘s marriage to Isabel of Gloucester was annulled shortly after his accession, and she was never crowned; Henry IV‘s first wife Mary de Bohun died before he became king.

- ^ No record of Elizabeth’s birth survives. She was the product of a secret marriage between Richard Woodville, a prominent English gentleman, and Jacquetta of Luxembourg, the aristocratic eldest daughter of Peter I of Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol, Conversano and Brienne. The marriage caused a scandal when it came to public notice and the couple were fined, and, on 24 October 1437, pardoned for marrying without royal permission. David Baldwin conjectures that the pardon coincided with the birth of Elizabeth Woodville, the couple’s firstborn child. See Baldwin, David, Elizabeth Woodville: The Mother of the Princes in the Tower

- ^ Henry Tudor’s claim to the throne was weak, owing to a declaration of Henry IV that barred the accession to the throne of any heirs of the legitimised offspring of his father John of Gaunt by his third wife Katherine Swynford. The original act legitimizing the children of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford passed by Parliament and the bull issued by the Pope in the matter legitimised them fully, making questionable the legality of Henry IV’s declaration.

References[edit]

- ^ Karen Lindsey, Divorced, Beheaded, Survived, xviii, Perseus Books, 1995

- ^ A Complete History of England with the Lives of all the Kings and Queens thereof; London, 1706. p486

- ^ Kennett, White; Hughes, John; Strype, John; Adams, John; John Adams Library (Boston Public Library) BRL (16 June 2019). “A complete history of England: with the lives of all the kings and queens thereof; from the earliest account of time, to the death of His late Majesty King William III. Containing a faithful relation of all affairs of state, ecclesiastical and civil”. London: Printed for Brab. Aylmer … – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Jewell, Helen M. (1996). Women in Medieval England. ISBN 9780719040177.

- ^ Baldwin, David, Elizabeth Woodville: Mother of the Princes in the Tower

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Hicks, Michael (2004). “Elizabeth (c.1437–1492)”. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/8634. Retrieved 25 September 2010. (Subscription or UK public library membershiprequired.) (subscription required)

- ^ Jane Bingham, The Cotswolds: A Cultural History, (Oxford University Press, 2009), 66

- ^ Robert Fabian, The New Chronicles of England and France, ed. Henry Ellis (London: Rivington, 1811), 654; “Hearne’s Fragment of an Old Chronicle, from 1460–1470,” The Chronicles of the White Rose of York. (London: James Bohn, 1845), 15–16.

- ^ Ralph A. Griffiths, “The Court during the Wars of the Roses”. In Princes Patronage and the Nobility: The Court at the Beginning of the Modern Age, cc. 1450–1650. Edited by Ronald G. Asch and Adolf M. Birke. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-19-920502-7. 59–61.

- ^ Calendar of Patent Rolls, 1467–77, pg. 190.

- ^ Sutton and Visser-Fuchs, “A ‘Most Benevolent Queen;'”Laynesmith, pp. 111, 118–19.

- ^ C. T. Wood, “Richard III, William, Lord Hastings and Friday the Thirteenth”, in R. A. Griffiths and J. Sherborne (eds.), Kings and Nobles in the Later Middle Ages, New York, 1986, 156–61.

- ^ Charles Ross, Richard III, University of California Press, 1981 p81.

- ^ Philipe de Commines, The memoirs of Philip de Commines, lord of Argenton, Volume 1, H.G. Bohn, 1855, pp.396–7.

- ^ Genealogical Tables in Morgan, (1988), p. 709.

- ^ “Parliamentary Rolls Richard III”. Rotuli Parliamentorum A.D. 1483 1 Richard III Cap XV. Archived from the original on 1 September 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Richard III and Yorkist History Server Archived 9 July 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Rotuli Parliamentorum A.D. 1485 1 Henry VII – Annullment of Richard III’s Titulus Regius”. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ “Rotuli Parliamentorum A.D. 1485 1 Henry VII – Restitution of Elizabeth Queen of Edward IV”. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth: England’s Slandered Queen. Stroud: Tempus, 2006, 245.

- ^ Bennett, Michael, Lambert Simnel and the Battle of Stoke, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 1987, pp.42; 51; Elston, Timothy, “Widowed Princess or Neglected Queen” in Levin & Bucholz (eds), Queens and Power in Medieval and Early Modern England, University of Nebraska Press, 2009, p.19.

- ^ Breverton, Terry (15 May 2016). Henry VII: The Maligned Tudor King. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 9781445646060.

- ^ “Margaret of Denmark Facts, information, pictures”. Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Jump up to:a b J. L. Laynesmith, The Last Medieval Queens: English Queenship 1445–1503, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, pp.127–8.

- ^ Alison Flood (25 April 2019). “‘White Queen’ died of plague, claims letter found in National Archives”. The Guardian.

- ^ Roger, Euan C. (2019). “To Be Shut Up: New Evidence for the Development of Quarantine Regulations in Early-Tudor England”. Social History of Medicine: 5–7. doi:10.1093/shm/hkz031.

- ^ Richardson, Douglas (2011). Magna Carta Ancestry: A Study in Colonial and Medieval Families, ed. Kimball G. Everingham II (2nd ed.). Salt Lake City. ISBN 1449966381, pp 304–7

- ^ Stanbury, Sarah (2005). “Middle English Religious Lyrics”. In Duncan, Thomas Gibson (ed.). A Companion to the Middle English Lyric. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 227–41. ISBN 9781843840657.

- ^ McNamer, Sarah (2003). “Lyrics and romances”. In Wallace, David; Dinshaw, Carolyn (eds.). The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Women’s Writing. Cambridge UP. pp. 195–209. ISBN 9780521796385.

- ^ Barratt, Alexandra, ed. (1992). Women’s Writing in Middle English. New York: Longman. p. 275-77. ISBN 0-582-06192-X.

- ^ “Astrophel and Stella: 75”. utoronto.ca.

- ^ “Elizabeth Woodville Primary School”. Elizabethwoodvilleprimaryschool.co.uk. Retrieved 5 September2016.

- ^ “The Elizabeth Woodville School”. Ewsacademy.org. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ Boutell, Charles (1863). “A Manual of Heraldry, Historical and Popular”. London: Winsor & Newton: 277.

Further reading[edit]

- Philip Butterworth and Michael Spence, ‘William Parnell, supplier of staging and ingenious devices, and his role in the visit of Elizabeth Woodville to Norwich in 1469’, Medieval English Theatre 40 (2019) [1]

- David Baldwin, Elizabeth Woodville (Stroud, 2002) [2]

- Christine Carpenter, The Wars of the Roses (Cambridge, 1997) [3]

- Philippa Gregory, David Baldwin, Michael Jones, The Women of the Cousins’ War (Simon & Schuster, 2011)

- Michael Hicks, Edward V (Stroud, 2003) [4]

- Rosemary Horrox, Richard III: A Study of Service (Cambridge, 1989) [5]

- J.L. Laynesmith, The Last Medieval Queens (Oxford, 2004) [6]

- A. R. Myers, Crown, Household and Parliament in Fifteenth-Century England (London and Ronceverte: Hambledon Press, 1985)

- Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth Wydeville: The Slandered Queen (Stroud, 2005); Elizabeth: England’s Slandered Queen (paper, Stroud, 2006) [7]

- Charles Ross, Edward IV (Berkeley, 1974) [8]

- George Smith, The Coronation of Elizabeth Wydeville (Gloucester: Gloucester Reprints, 1975; originally published 1935)

- Anne Sutton and Livia Visser-Fuchs, “‘A Most Benevolent Queen’: Queen Elizabeth Woodville’s Reputation, Her Piety, and Her Books”, The Ricardian, X:129, June 1995. PP. 214–245.

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elizabeth Woodville. |

Scheming Facts About Elizabeth Woodville, The Commoner Queen

Cross breed Game of Thrones with Cinderella, and you’ll get Elizabeth Woodville’s life story. Despite her lowborn roots, she used her beauty to catch the eye of King Edward IV and become the first common-born Queen of England. Once she had her crown, she’d do anything—and I mean anything—to keep it. Get to know Elizabeth Woodville, England’s infamous “White Queen.”

Elizabeth Woodville Facts

1. She Started From The Bottom

In truth, Elizabeth Woodville wasn’t really a “peasant” queen. On her father’s side, she was descended from knights, sheriffs, members of Parliament, and other ancestors of gentlemanly vocation. This was nothing to turn your nose at, but back in the 1400s, it was hardly the pedigree that people expected from the future queen of the nation.

2. She Had Scandalous Roots

As the first child of a controversial couple, scandal was in Elizabeth Woodville’s blood. Her mother was the widow of King Henry V’s younger brother. But when it came time to choose husband number two, she passed on the royals and wed a mere knight named Sir Richard Woodville. The mismatched couple dropped jaws at the English court and infuriated the king.

3. She Was A Bad Girl From The Start

Elizabeth Woodville’s parents were literal outlaws. You see, her mother had to get permission from the king to remarry, but in her haste to tie the knot, she skipped that step. The king was ticked and promptly fined the newlyweds a hefty £1,000 for getting hitched without his royal blessing. How many other queens of England can say that their birth was literally against the law?

4. She Was Hot Stuff

Tudor portraits aren’t exactly flattering, but by all accounts, Elizabeth Woodville was hot stuff. She was statuesque with shining blonde hair, fair skin, and entrancing eyes. In a painting of Woodville, they look hazel, but sources describe them as “lynx eyes” and “the eyes of a dragon.” Some historians believe that Woodville’s eyes were a striking light green or even golden.

Advertisement

5. She Got Married Young

The 1400s weren’t about waiting around—they was about making babies as soon as possible. To do her part, Elizabeth Woodville walked down the aisle when she was just 15 years old and married a knight named Sir John Grey. Soon enough, Woodville won the Medieval jackpot and gave birth to two sons. However, her wedded bliss wouldn’t last very long.

6. Her Family Was Torn Apart

Long story short, during the Wars of the Roses, the Yorks and the Lancasters played an exhausting, bloody game of Crown Swap. After decades of conflict, the Lancasters lost and King Edward IV took the throne. For the Yorks, this was great. But for Elizabeth Woodville, who was a Lancaster through and through, it was a disaster. And the bad news kept coming.

During the final phases of the conflict, enemy forces captured her brother and father.

7. She Lost Her Husband

Before Woodville and Grey even reached their tin anniversary, their marriage was already done. Woodville’s first husband fought in the brutal Battle of St. Albans and unfortunately, he didn’t make it out alive. With her husband’s passing, Woodville became a 28-year-old widow and a single mother—and now she had to deal with her hellish in-laws all alone.

8. Her In-Laws Were Evil

Get this, when Grey perished, his parents point-blank refused to help Elizabeth or her children (who were also, I must point out, their own grandchildren!). Although Woodville was promised money in her marriage settlement, her in-laws refused to send her any funds to help her and her children survive. Desperate, poor, and widowed, Woodville only had one option left for survival.

Betray her family’s Lancastrian roots and beg the new king to help her out.

9. She Defied The Odds

Woodville’s evil in-laws weren’t budging, so to get her money, our girl had to take her fight to the new king…who was awkwardly her sworn enemy. However, their meeting didn’t exactly go according to plan and in the end, Woodville got a heck of a lot more than she bargained for. She went hoping to receive a pittance—and she left with a wedding ring and a crown. Here’s how.

Sign up to our newsletter.

History’s most fascinating stories and darkest secrets, delivered to your inbox daily. Making distraction rewarding since 2017.

10. She Caught A King

How does a single mom meet a guy who will treat her like a queen? In the days before dating apps, all you had to do was stand under an oak tree and wait for the king to ride by—or at least, that’s all it took for a hottie like Elizabeth Woodville. In this version of King Edward IV and Elizabeth’s meet-cute, our gal used her legendary beauty to catch the king’s eye. As Elizabeth explained her plight to the king, he was instantly smitten.

Advertisement

11. He Put A Ring On It

In some tellings of their “love” story, Edward meets Elizabeth, immediately falls for her, and insists that she become his mistress. Woodville resists the king’s advances and plays hard to get, which obviously leads Edward to become even more obsessed with his new flame. In some versions of this story, Liz plays her cards so well that after meeting the king, she goes from destitute widow to queen in just three weeks.

However, another version of their meeting isn’t so romantic.

12. She Was Pushed To The Edge

King Edward IV was a legendary horndog and dude was used to getting any girl he wanted. So when Woodville resisted him, some sources claim that he responded…poorly. Apparently, Woodville had to threaten to end her own life to make him back off before their wedding night. And in other versions of the tale, things get even worse.

13. He Had A Dark Side

According to some legends, it was actually Edward who wielded a knife against Elizabeth. Apparently, when she refused to go to bed with him, the king held the blade to her throat and forced her to submit to his advances. Romantic! Thankfully, many scholars believe that this particular version of their meeting is just dramatic embellishment.

14. They Got Hitched

No matter how they met, here’s what we know for certain: It didn’t take long for Edward and Elizabeth to make things official. By May of 1464, the king and his commoner bride got hitched. The new couple tied the knot in a ceremony at a chapel in Woodville’s family home in Northamptonshire. But there was a twist to this royal wedding.

15. They Wed In Secret

When you think of a royal wedding, you think pomp and circumstance. But that was not the case at Edward and Elizabeth’s wedding. It was a modest affair and the only witnesses were the bride’s mother and a few of her attendants. Why? Oh, because the marriage was top secret. Edward knew that marrying a commoner wouldn’t go over well with his advisers, so he threw caution to the wind, had an impulsive Vegas-style wedding, and let Future Edward deal with the blowback.

This plan went about as well as you’d expect.

16. Her Husband Was A Player

Courtiers weren’t the only ones who’d be ticked to learn about the wedding. You see, when it came to the ladies, Elizabeth’s new hubby had a policy of “promise to marry it, hit it, and then quit it.” In fact, at the same time as Elizabeth married the king, it was rumored that Edward’s previous mistress was heavily pregnant and waiting for her marriage to the king. I see an awkward conversation in Liz and Ed’s future.

Advertisement

17. She Made History

Despite all the messiness and scandal surrounding Elizabeth Woodville’s marriage to King Edward IV, her wedding was still straight out of a fairy tale. Before tying the knot, Elizabeth was your average well-to-do gal. After, she was the Queen of England. With her marriage, Elizabeth became the first “Commoner Queen” of England, setting the stage for women like Kate Middleton and Meghan Markle.

Liz must have been happy with her advantageous match—but Edward’s advisers? They were furious.

18. Her Marriage Was Controversial

Edward’s key adviser, the infamous “Kingmaker” Richard Neville had been busy setting up a strategic French marriage for the king. Everything was locked and loaded—until Edward revealed that actually, he couldn’t marry a French hottie because he’d already eloped with Woodville. The faux-pas made Neville seem like a lying fool in the eyes of the French court. Angry and embarrassed, Neville would hold a murderous grudge against both the king and Woodville herself for years to come.

19. The Court Hated Her

Neville wasn’t the only one who hated the idea of Queen Elizabeth Woodville. All of the English nobles were ticked. Contemporary accounts called Elizabeth “undistinguished,” and rumors about Woodville’s super seductress ways spread far and wide. The people believed that the king had been led by his, ahem, nether regions and that the impulsive match was a huge mistake. Oh, and that wasn’t all.

20. She Liked Younger Men

As though being a commoner and a widow wasn’t controversial enough, did I mention that Elizabeth Woodville was also a bit of a cougar? At 28, she was a scandalous five years older than her new husband.

21. Dark Rumors Spread

Here’s a sign of how much the people hated Liz. After news of the king’s marriage broke, a dark rumor spread through England. It claimed that Edward’s wedding didn’t count because—get this—Edward was illegitimate. The story went that when Edward’s mother was over in France, she had a spicy affair and that Edward was the result of that romance, not the queen’s marriage to the king. But that’s not even the wildest part of the story.

22. Her Mother-In-Law Detested Her

The king’s mother—the woman whose reputation was being dragged through the mud with this rumor—did very little to stop it. In fact, some historians believe that she spread the rumor herself (!) or instructed one of her ladies-in-waiting to start the gossip. This woman hated Elizabeth so much that she scorched-earthed her own reputation and the reputation of her son to get her new daughter-in-law out of the picture.

Advertisement

23. She Had A Glam Coronation

Yeah, everyone hated Elizabeth Woodville, but like it or not, she was the new queen and new queens get lavish coronations. Edward cleverly used the occasion as a way to legitimize his new bride. He hired people to dress as angels, bought Elizabeth an expensive purple gown, and even made London smell okay which, back in the 1400s, was a big achievement.

Thankfully, all these expenses did the trick. On May 26, 1465, the coronation’s pomp and splendour, along with Elizabeth’s jaw-dropping beauty, won the people over—for now, at least.

24. Her Family Made Trouble

Elizabeth Woodville’s enormous family hitched a ride on her rising star in a big way. The Woodville clan shamelessly used their new fancy-pants status as the king’s in-laws to ensnare wealthy husbands and wives. Most scandalously, Woodville’s 20-year-old brother John married the Duchess of Norfolk, who a whopping 65 years old at the time.

This was a power grab, plain and simple—and the Woodvilles were not being subtle about it. Their actions were guaranteed to ruffle feathers at court.

25. She Made Enemies

Remember Elizabeth’s enemy, the Kingmaker Richard Neville? Well, all these advantageous Woodville marriages only made him hate Elizabeth more. He felt that his family were the ones who should have been marrying up, not the ambitious Woodvilles. As he watched Elizabeth’s relatives call dibs on all the eligible court hotties, he saw his family’s chances to gain power go up in smoke. And then, Elizabeth went too far.

26. She Got Revenge

Neville’s nephew was supposed to nab a wealthy heiress—until Elizabeth pettily stole the girl away and married her off to her own son. With this final insult, Neville officially lost it. In 1470, he lashed out against the royal couple. He partnered up with King Edward’s ambitious younger brother and staged a rebellion to replace King Edward with England’s old ruler, Henry VI.

27. Everything Fell Apart

While Neville staged his coup, King Edward told Elizabeth to run away and take shelter with her children. Elizabeth got out of dodge just in the nick of time. After she left, everything devolved. Enemy forces captured Edward, then his commanders screwed the pooch and lost a major battle. When all was said and done, King Henry VI reclaimed the throne, while King Edward and Elizabeth Woodville lost everything.

28. She Lost Loved Ones

Unfortunately for Elizabeth, things would get worse before they got better. Richard Neville, the mastermind behind Henry’s takeover, made things personal. He declared that Elizabeth and her mother were witches and that Elizabeth had used dark magic to ensnare King Edward IV. Not content with ruining the reputations of Elizabeth and her mom, Neville then did something far worse. He captured and beheaded Elizabeth’s brother and father.

29. She Went Into Hiding

In a matter of months, Elizabeth had gone from the queen of England to a desperate, grieving mother. In 1470, her husband had been exiled to France and she had moved into Westminster Abbey to hide from her enemies. As though that wasn’t enough for Woodville to deal with, the entire time this mess was going down, Elizabeth was heavily pregnant.

30. She Did Her Duty

Elizabeth Woodville was one tough lady. Even though her life was a dumpster fire, she persevered and gave birth to a baby boy in the basement of Westminster Abbey. She named her son Edward and, even though she and her hubby had technically been deposed, Elizabeth ignored that little detail and thought of the infant as the heir to the throne of England.

Little did she know, she was right to get her hopes up. A lot had happened while Liz was locked up in Westminster…

31. Her Fortunes Changed

By May of 1471, King Edward had staged a legendary comeback. He rallied his French allies, persuaded one of Neville’s co-conspirators to switch sides, and charged back into England to defeat the infamous Kingmaker. After a decisive victory at Barnet, Edward deposed his competition and reclaimed his crown. Richard Neville, meanwhile, fell off his horse and got trampled. Boy, bye.

With her husband back as king, Elizabeth Woodville re-entered the real-life game of thrones.

32. She Got Busy

After all Elizabeth’s ordeals, she could finally sit back and relax. For the next decade, she spent most of her time doing what all queens had to do: Makin’ babies. Although King Edward’s womanizing ways meant he was hardly faithful to Elizabeth, the couple had a whopping ten children, including that all-important heir, Prince Edward.

However, as the years went by, Elizabeth’s experience with motherhood became utterly horrific.

33. Her Husband Was A Bad Boy

Back in the 1400s, queens just had to deal with their husbands having mistresses. But even the most understanding wife would have issues with King Edward’s bottomless lust. He had three major mistresses and plenty of flings on the side, including one rumored relationship with another man, Henry Beaufort. Meanwhile, Elizabeth repaid her hubby’s affairs with complete loyalty. Worth it for the crown?

34. Her Brother-In-Law Was Trouble

Even though England was finally peaceful, drama never slept for long in King Ed’s castle. This time, the king’s brother George was the one causing trouble. He had a, shall we say, tense relationship with King Edward and Queen Elizabeth. George had betrayed Edward in past battles and he was also a big part of why Elizabeth’s father and brother had been executed, so you can’t really blame them for not liking the guy. But then things got incredibly messy. Like, impending body count messy.

35. He Tried To Punish Her

George kept trying to marry high-status women in King Edward’s court. I say “trying” because every time he got close to putting a ring on it, Edward (and Elizabeth, goading her man on from the background) would mess up the match to keep George from getting too powerful. After the royal couple kaiboshed George’s love life one too many times, he got ticked, left the court, and started scheming against Ed and Liz. Do you think this will go well for him? Me neither.

36. She Got Him Back

As a warning that George should back the heck off, Edward charged some of his brother’s friends with a serious offence: Using dark magic to destroy both Edward and his heir. Anyone with half a brain would have reined in their schemes at this point—but not George! He kept on keeping on, and in the end, he found himself drowned in a barrel of wine.

Historians believe that Elizabeth was in on George’s brutal punishment. It was belated payback for his role in the demise of her family.

37. She Bided Her Time

Despite her occasional lapses into Quentin Tarantino-style violence, most of the time, Queen Elizabeth was a pretty tame, traditional queen. She invested heavily in acts of Christian charity and piety, said Angelus devotion three times a day, and was heavily involved in her children’s upbringings. Her days were pretty normal—until, once again, everything fell down around her.

38. Her Husband Passed

In April 1483, Elizabeth’s husband passed under ambiguous circumstances at just 40 years old. Some say that he had “a chill”; others insist that his debauched ways had finally caught up to him. No matter what caused the king to keep over, his demise left Elizabeth Woodville a widow and single mother to the future king. During the turbulent 1400s, this was a very dangerous position to be in. Elizabeth knew that to ensure her safety—and the safety of her family—she’d have to act fast.

39. Her Entire Life Changed In An Instant

In the king’s will, Edward appointed his brother, Richard the Duke of Gloucester, to become the Lord Protector of little Prince Edward, the heir to the throne. Unfortunately, it turns out that Richard was incredibly ambitious. With his big brother out of the picture, he immediately used his new position to grab power for himself. He promised Elizabeth that he’d keep Prince Edward safe, but unfortunately, he lied. Big time.

40. Her Foe Targeted Her Family

After getting his hands on Prince Edward, Richard went to work destroying the rest of Elizabeth’s family. He arrested both her brother and one of her sons from her first marriage, Richard Grey, then suspiciously delayed the coronation of Prince Edward. Sensing that the tides were turning and her entire family would soon be in big trouble, Woodville rushed herself into sanctuary once again.

41. He Ran Her Name Through The Mud

While Elizabeth hid out at an abbey with her children, Richard was busy running one heck of a PR campaign. He made the public think that he was somehow protecting the Prince, instead of, y’know, abducting him and trying to usurp his power. He also ran Elizabeth’s name through the mud. In 1483, he accused her of trying to “murder and utterly destroy” him from her sanctuary. Not sure how that would work, but OK, bud.

42. She Had No Choice

To be fair to Richard, Elizabeth probably did want to wring his neck, but at this particular moment in time, he had all of the power and she had none. Case in point: When Richard was no longer satisfied with just abducting the heir to the throne, he turned his eye to the spare as well. His men surrounded the abbey where Elizabeth Woodville was hiding and demanded that she hand over her other son. Elizabeth’s reaction to this demand has puzzled historians for centuries.

43. She Lost Her Son

Prepare to rage. Defying all her maternal instincts, Elizabeth handed over her son. Yes, this was a TERRIBLE idea, but in Elizabeth’s defence, she didn’t really have a choice. In most versions of this story, Elizabeth only gives the boy up because she is under extreme duress. She’s literally surrounded by Richard’s men, so after making the archbishop promise that her son won’t be harmed, she reluctantly gave Richard the boy. Reader, this was a huge mistake.

44. Her Babies Were Locked Up

This is the point where Richard gives up all pretence of being a protective uncle. He makes it clear that he’s out for power and that anyone standing in his way is toast. First, he executes Elizabeth’s brother and one of her sons from her first marriage. Then, despite all his promises to the contrary, he imprisons Elizabeth’s beloved sons, Prince Edward and his little brother, in the Tower of London.

45. Cruel Rumors Spread

Elizabeth must have been terrified for her sons—but all she could do was stay in the sanctuary and try to protect her other children while Richard spread vicious rumors about Elizabeth, Edward, and their kids all through England. In a bid to take Prince Edward’s power, Richard declared that actually, it was okay for him to lock up two innocent little boys because they weren’t actually legitimate. Plot twist, right?

46. She Was Disgraced

Remember when Edward’s mom was like, “Edward can’t make that common lady a queen because I actually had an affair with a random French guy and he is Edward’s real dad”? Well, Richard brought that back up to claim that the princes couldn’t lead the nation because ipso facto, they too were illegitimate. And then just to prove how much of a turd he was, Richard went even further.

47. Her Marriage Was Cancelled

The lurid romantic history of Woodville’s late husband came back to bite her in the royal rear. In 1483, Richard declared that Woodville’s marriage didn’t count for a shocking reason. When she wed the king, Edward had already promised to marry his old mistress—and back in the 1400s, a promise was as good as a wedding ring.

But just to make sure that Woodville couldn’t fight back, Richard covered his bases with an even worse claim about Elizabeth and Edward’s marriage.

48. Her Husband Was Manipulative

When Richard defamed somebody, he went hard. He claimed that the “priest” who married Liz and Ed was a fraud and thus their marriage never actually happened. Apparently, Edward would take resistant mistresses to a buddy who’d pretend to be a priest and fake-marry the couple. Once the girls thought they had a ring, they hopped into bed with Edward, who’d then love em and leave em. What. A. Guy.

49. Her Power Was Gone

After spreading all the dirt, Richard dissolved Elizabeth’s marriage to Edward, declared the Woodville children illegitimate, and barred them from inheriting the throne. He deposed Prince Edward in 1483, declared himself King Richard III of England, and for good measure, threw in one final reminder that Elizabeth Woodville was a witch. Then he hurt the ex-queen in the worst way possible.

50. Her Sons Became A Historical Cold Case

After the summer of 1483, when Elizabeth reluctantly handed over her two sons to Richard III and his henchmen, there would be no more sightings of Woodville’s sons. The lost boys are now known to history as the tragic “Princes in the Tower.” No one knows for sure what happened to them, but for centuries, people have believed that Richard executed the brothers. They were just 12 and nine years old at the time.

51. She Gave Up

During Richard III’s reign, Elizabeth Woodville’s life was miserable. She was stripped of her royal title and lands. Her daughters were bastardized and she would henceforth be known as “Dame Elizabeth Grey,” in reference to her first husband. After holding out hope that her sons might emerge from the Tower, she eventually gave up. By the autumn of 1483, she accepted that she would never see her babies again. Poor Elizabeth.

52. She Made Friends With An Old Foe

Say what you want about her, Elizabeth Woodville was a survivor. When the going got tough, she put on her game face and did what she had to do. Case in point: During her time in the sanctuary, she made an unlikely ally. Elizabeth teamed up with her deceased husband’s chief mistress (and Elizabeth’s own great rival) Jane Shore. With Shore’s help, the widowed queen stayed in contact with her allies—and plotted an ingenious revenge.

53. She Plotted

Woodville defied everyone’s expectations by working with another old frenemy, Margaret Beaufort, and trying to bring Richard down. In October of 1483, the women became involved in Buckingham’s Rebellion. The plan was stunning: Beaufort’s son Henry Tudor would come to England, defeat Richard, take the throne, and marry Woodville’s daughter, thus uniting both Yorks and Lanacasters.

Unfortunately, things, um, didn’t go to plan.

54. She Had To Do The Unthinkable

Richard III caught wind of the rebellion and immediately shut it down, putting Elizabeth in a tricky situation. She effectively had to make a deal with the devil AKA Richard himself. Woodville said that if Richard let her and her daughters safely leave the abbey, she wouldn’t make any more trouble for him. Richard agreed—but he had one sickening condition. Elizabeth had to live at his court and tacitly support his reign.

Yup, if Elizabeth wanted to survive, she’d have to play nice with the man who killed her sons.

55. Her Daughter Was In Danger

In the end, Woodville and her daughters took Richard’s deal. They came out of religious sanctuary in March 1484, hung out in their enemy uncle’s court, and bided their time until Henry Tudor made another attempt at a takeover. But it’s not as though this period was uneventful. At this time, Richard decided that he had the hots for Woodville’s eldest daughter (and yuckily his own niece), Elizabeth of York. With this skeezy development, I’m sure that Woodville was plenty busy.

56. Everything Changed

Thankfully, things were about to change in a big way. Henry VII invaded England in 1485, defeated Richard III, and successfully seized the throne. In his victory speech, the new King Henry declared that little Prince Edward was legitimate, then restored Elizabeth Woodville back to her former glory as Dowager Queen. At long last, she got all her land and money back. Whoo!

But if you think Henry was doing this out of the goodness of his heart, guess again…

57. She Was Redeemed

Henry’s kindness to Elizabeth and her kids wasn’t purely altruistic. It was also a way for him to bolster his own power. After all, he stuck to the plan where he’d marry Woodville’s daughter—and it wasn’t like a king could marry a disgraced woman. By re-fancying Elizabeth, the new king also re-fancied her daughter and crucially, his future bride.

With this advantageous marriage completed, Elizabeth was ready to settle back into court. But life had other plans.

58. She Was Kicked Out

After defeating Richard III, Woodville and her old frenemy Margaret Beaufort went back to their old rivalrous ways. They drove each other nuts in a petty battle of the Dowager Queens and eventually, Beaufort edged Woodville out. After this defeat, the ex-queen got shuttled to yet another sanctuary. However, another version of the story claims that Elizabeth left the court for a far darker reason.

59. She Rebelled

In 1487, a ten-year-old boy named Lambert Simnel claimed that he was actually one of the infamous princes in the tower and he was coming back to claim his throne. Seeing as this was an uprising led by a literal child, it’s not surprising to learn that Henry VII shut it down fast. But even though he quelled the rebellion, the king suspected that Elizabeth Woodville had been involved in some capacity. Was this the real reason that he shuttled her off to another abbey?

60. She May Have Fooled Everyone

Ultimately, we don’t know if Woodville truly was involved with the Simnel uprising. However, there are persistent rumors that one of her sons survived the Tower of London. Some sources claim that when Woodville handed over her child to Richard, she actually handed over an imposter—which would mean that Woodville’s real son (and King Edward’s heir) was still alive at this time. Most historians think these are just conspiracy theories, but who knows?

61. She Went Into Retirement

Some people say that Woodville went to her latest abbey kicking and screaming. Others insist that the Dowager Queen went to retirement more willingly. This is based on evidence that the queen was already planning her retirement into a religious life as early as one year into Henry Tudor’s reign. After losing her father, brothers, and sons to the violence of court politics, it’s not a stretch to imagine that Woodville would welcome some peace and quiet.

Well, she’d finally get them in February of 1487—but not for long.

62. She Almost Got Hitched

With his widowed mother-in-law far away from rebellions, King Henry VII decided to make the most of Elizabeth’s status as a single lady. He played matchmaker and tried to set Elizabeth up with yet another ruler: King James III of Scotland. The match would have cemented Woodville’s cougar reputation, seeing as how she would have been in her fifties, while new new hubby was in his thirties. Unfortunately, it didn’t happen for a terrible reason.

63. She Lived The Single Life

Despite Henry VII’s attempts to play Cupid, the match between James and Elizabeth came to naught. The king passed in battle (or, depending on who you ask, while running away from the fight) in 1488. After that, Woodville remained at the single’s table for the rest of her life, where she chilled out in a church until her own equally dramatic demise.

64. Her Retirement Is Suspicious

Working against the idea that Henry VII shunned his mother-in-law, Elizabeth Woodville seems to have had a sweet time in the abbey. She retired to a nice £400 per year pension and received occasional gifts from the Tudor king. She also enjoyed visits from her daughters, most often by Cecily of York. However, towards the end of her life, Elizabeth insisted that this wasn’t the whole story.

65. She Lived In Poverty

During Woodville’s final five years in religious seclusion, she insisted that she didn’t actually receive the cash injection promised by King Henry VII. Instead, she spent her time in abject poverty. In fact, in Woodville’s will, she laments that though she is “the God Queen of England” she has “no worldly goods” and could not even afford to “reward my children.” Yikes.

66. She Hated Her Son-In-Law

I think it’s safe to say that over the years, Henry VII and Elizabeth Woodville’s relationship had soured pretty intensely. Even though he was A) the king, B) her son-in-law, and C) the only reason she’d escaped from the clutches of Richard III, Elizabeth very conspicuously does not mention Henry in her last will and testament. Sounds like some icy family dinners went down in the castle…

67. She Passed On

And so, after 55 years of nonstop drama, Elizabeth Woodville’s health began to deteriorate. On June 8, 1492, she finally breathed her last breaths at Bermondsey Abbey, where she had retired/been low-key imprisoned for the last five years. The royal family said goodbye to their mother and prepared for her funeral at Windsor Castle. But when they arrived at the ceremony, their jaws dropped.

68. Her Funeral Was Insulting

Even though Elizabeth was a Dowager Queen, her funeral was downright shabby. Usually, royal funerals cost about £1500. Hers looked like it cost just £100. A mere five attendants carried Elizabeth’s coffin, the bells did not toll in her honor, and she didn’t even receive the traditional funerary rights. Her coffin was basically buried as soon as humanly possible.

This was a huge slap in the deceased queen’s face—but why?

69. Her Burial Stunned Historians

Some people took the drabness of Woodville’s 1492 funeral as evidence that the new Tudor dynasty really hated her. However, other people insist that the self-secluded queen dowager wanted it this way. After all, she specifically requested a simple, plain burial in her last will and testament. But recently uncovered evidence has suggested a much more likely—and much more disturbing alternative.

70. The Truth Finally Came Out

Over 500 years after Queen Elizabeth Woodville’s demise, we may finally know why her funeral was so slapdash. In 2019, a historian uncovered a letter that confirmed that Woodville had perished of the strange plague often called the “sweating sickness” (gotta say, that doesn’t sound like a great way to go). In an effort to avoid spreading the disease, the royal family decided to bury the Dowager Queen as quickly as possible and get the heck outta there.

71. She Had A Huge Impact On Henry VIII

In the letter about Woodville’s plague infection, the writer also mentions that her illness profoundly disturbed the King. Well, apparently Henry VII passed down his fears to his son, the infamous Henry VIII. He was incredibly anxious about the illness that ended his grandmother’s life, even sleeping in different beds every single night in a strange effort to…outrun it?

72. Her Resting Place Is Heartbreaking

In the end, Woodville was buried in the same chantry as her beloved, rascally second husband, Kind Edward IV. To this day, they lie together at St. George’s Chapel inside Windsor Castle.

73. Her Daughter Was A Bad Girl Too

Woodville’s younger daughter Cecily followed her mother’s path by making another interclass remarriage. Unfortunately for Cecily, she took a step down rather than up. By marrying an obscure squire named Thomas Kyme, Cecily forfeited all her lands and got banished from court. Her children by that marriage faded into obscurity. Hardly the courtly welcome her mother enjoyed for her elopement.

74. She Has A Surprising Legacy

Queen Elizabeth Woodville’s legacy lives on in our modern day. You can visit the “Queen’s Oak” (the legendary site of the oak tree where Elizabeth and Edward IV first met) and the borough of Queens in New York City is actually named after Woodville.

75. She’s Part Of A Major Landmark

Queens’ College at Cambridge University was originally set up by the Lancastrian Queen Margaret of Anjou. It collapsed as the Lancastrian regime crumbled in 1448, but Elizabeth Woodville stepped up in 1465 to help bring it back to life. Because of this, she’s credited with helping to found the legendary college. A pretty impressive legacy!