How Manufactured Crisis, Programmed Rage, and Misguided Resistance Prolonged Human Suffering

By Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D. (Anthropology, UCLA)

With Contributing Author Janet Kira Lessin

INTRODUCTION

Wars do not erupt spontaneously. They are prepared for—psychologically, politically, and mythologically—long before the first bombs fall. The Vietnam War stands as one of the clearest modern examples of how domination consciousness operates: fear is cultivated, events are distorted, and entire populations are mobilized against their own long-term interests.

The cost of Vietnam cannot be measured only in lives lost, but in generations traumatized, trust destroyed, and resources diverted away from healing, education, and shared prosperity. It remains a case study not merely in military failure, but in narrative failure—one that power would spend the next sixty years studying carefully.

In this account, Solomon Centers, a fictional composite figure drawn from lived experience, appears as a reflective guide—not a hero of violence, but a witness to how war programming overtakes rulers and resisters alike. Solomon is blue-eyed, clean-shaven, his wavy brown hair lightly threaded with white and neatly combed over his ears. He wears a simple white tunic and pandanus sandals, a reminder that wisdom does not require uniforms, medals, or weapons.

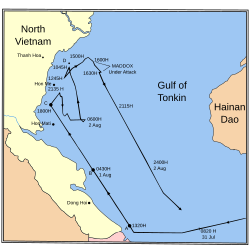

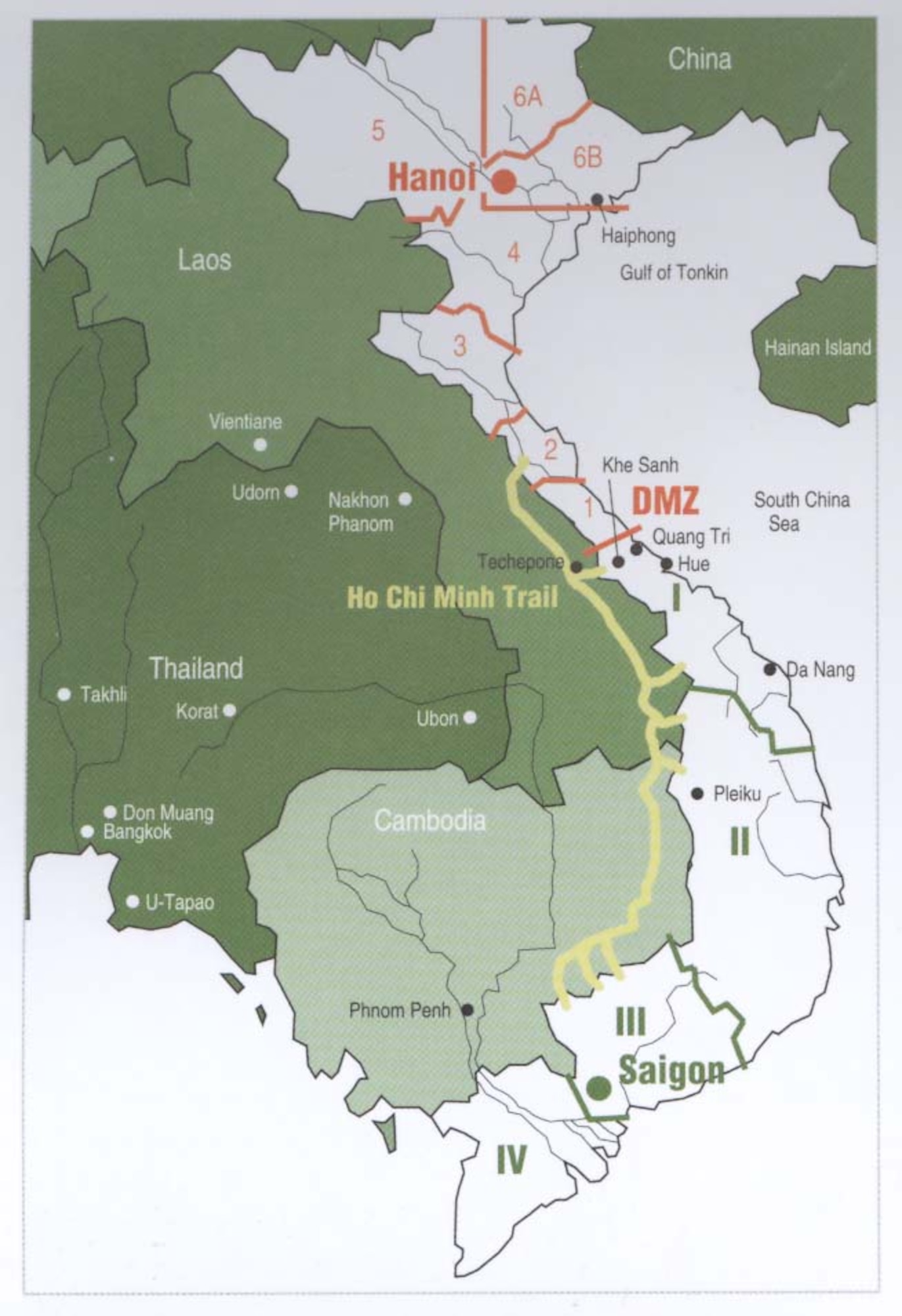

GULF OF TONKIN — THE SPARK THAT WASN’T

Solomon Centers stood quietly before a chalkboard marked with dates, naval routes, and arrows cutting through the Gulf of Tonkin. Wars begin, he told his students, when leaders decide the public must be frightened enough to accept them.

In August 1964, the Johnson administration claimed that North Vietnamese forces had attacked U.S. naval vessels. This allegation—especially the supposed second attack—was used to rush the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution through Congress, granting sweeping authority to escalate military action in Southeast Asia.

Later admissions and declassified material revealed that no such second attack occurred. Intelligence had been misinterpreted, exaggerated, or invented outright. At the same time, covert U.S. operations against North Vietnamese coastal targets were already underway, undermining claims of unprovoked aggression.

Howard Zinn documented this episode as a textbook case of manufactured justification for war, noting how what the government told the public bore little resemblance to what had actually happened.

GULF OF TONKIN: AMBIGUITY AS PRETEXT

A visual grounding of the contested waters where ambiguity enabled rapid escalation. Realistic historical map illustration, Gulf of Tonkin 1964, naval routes, Southeast Asia coastline, subdued documentary tones, landscape orientation.

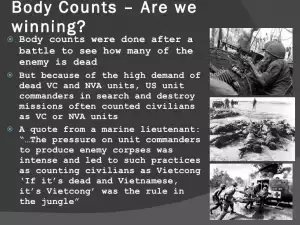

MEDIA, FEAR, AND THE SELLING OF WAR

Solomon reminded his students that wars are not fought only on battlefields. They are fought in newspapers, broadcasts, and classrooms.

Sensational headlines and selective reporting transformed uncertainty into certainty and suspicion into outrage. Context disappeared. Doubt became disloyalty. Complex regional dynamics were reduced to moral absolutes. The repetition of official claims hardened into assumed truth.

Chris Harman situated Vietnam within a broader global pattern: wars framed as moral crusades often mask struggles over power, influence, and economic control. Ordinary people are asked to sacrifice, while elites rarely bear the consequences.

When fear becomes the organizing principle, Solomon observed, critical thinking is treated as treason.

Television news as the primary battlefield of persuasion during Vietnam. Realistic 1960s television newsroom, Vietnam War broadcast, body count graphics.

THE ANTI-WAR MOVEMENT — COURAGE AND CONTRADICTION

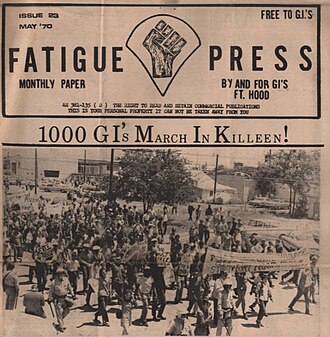

Resistance arose quickly. Students, veterans, clergy, and families challenged the war’s legitimacy. Many acted from deep moral conviction and genuine compassion for human suffering.

Solomon Centers advised students during those years. He respected their courage—and worried about their direction.

Opposing domination, he told them, requires discipline. If resistance adopts the tools of domination, it risks reproducing the very system it seeks to dismantle. Some factions drifted toward aggression, property destruction, and romanticized violence. In doing so, they alienated potential allies and allowed the state to portray all dissent as dangerous.

The tragedy, Solomon believed, was not protest itself, but the loss of ethical clarity under pressure.

Mass resistance that shook the nation while struggling to hold ethical coherence.

Realistic historical protest scene, 1960s anti-war demonstration, students and veterans, emotional but restrained tone.

HISTORIANS AND WITNESSES SEE THROUGH THE LIES

Howard Zinn insisted that historians must stand with those who suffer the consequences of policy, not with those who manufacture justifications for it. His work exposed how official narratives concealed deception while ordinary people paid the price.

Chris Harman reinforced this view, showing how Cold War ideology reframed local struggles as existential threats requiring military solutions that only intensified violence.

Thom Hartmann, who himself participated in anti-war activism during the Vietnam era, later emphasized how media systems and political institutions condition populations to accept war by suppressing historical memory and critical context.

Solomon summarized their shared insight simply: when power repeats the same lie often enough, it becomes the background noise of daily life.

RESISTANCE FROM WITHIN THE RANKS

One of the least acknowledged aspects of the Vietnam War was resistance by the soldiers themselves.

GI underground newspapers, refusals of orders, equipment sabotage, and desertion revealed deep moral fractures within the military. Many soldiers recognized that the war they were fighting bore little resemblance to the one politicians described.

Solomon worked clinically with veterans whose trauma stemmed not only from combat, but from the realization that they had been used.

When soldiers stop believing the story, Solomon reflected, the war is already lost—even if the bombing continues.

The war fracturing internally among those ordered to fight it. Realistic Vietnam-era military scene, GI underground press, disillusioned soldiers

Realistic, cinematic split-scene illustration set in the late 1960s, documentary realism. On the left side: a young, beardless male college professor in his early 30s, tall and slim, with wavy light-brown hair and blue eyes, standing at a chalkboard at the University of Hawaii. He is analyzing maps, dates, and handwritten notes related to the Vietnam War. On the right side: a young American girl, approximately 9 years old, slim build typical of the 1960s, sandy-blonde hair with bangs, blue eyes, seated alone in a quiet living or dining room. She is watching black-and-white Vietnam War news on a small television. Her expression is serious, attentive, and emotionally affected, not fearful or sensationalized. The two scenes gently bleed into one another through lighting and composition, symbolizing shared historical experience rather than physical proximity. No interaction between the figures.

DOMINATION VS PARTNERSHIP — THE DEEPER PATTERN

The Vietnam War exemplifies an ancient pattern: domination consciousness demanding obedience, sacrifice, and silence. War divides populations, exhausts resistance, and redirects human creativity toward destruction rather than cooperation.

Solomon concluded with a quiet challenge. Peace is not passive. It is an active refusal to accept lies, rage, and false choices. The real revolution is learning not to mirror the violence we oppose.

The tragedy of Vietnam was not only the war itself, but how much human potential it consumed—potential that could have built schools, healed communities, and nurtured a partnership-based future.

🚧 Work in Progress

This article is part of an ongoing series examining how war narratives are manufactured, refined, and reused across generations.

👤 Authors

Sasha Alex Lessin, Ph.D. — Anthropologist (UCLA), author, researcher

https://www.enkispeaks.com

Janet Kira Lessin — Writer, editor, publisher

https://www.dragonattheendoftime.com

https://substack.com/@janetalexlessinphd

📚 References

Zinn, Howard. War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, 2nd ed., 2011.

Zinn, Howard. The Twentieth Century.

Harman, Chris. A People’s History of the World, 2017.

Hartmann, Thom. Vietnam-era commentary and later analyses.

🏷️ Tags

Vietnam War, Gulf of Tonkin, Manufactured Consent, War Propaganda, Anti-War Movement, GI Resistance, Howard Zinn, Chris Harman, Thom Hartmann, Domination Consciousness, Partnership Consciousness, Media and War, Imperial History

📣 PROMOTION COPY

X (Twitter):

Vietnam wasn’t inevitable. It was manufactured. A look at how fear, media, and power turned ambiguity into catastrophe—and what was learned afterward. #VietnamWar #ManufacturedConsent

Facebook:

Vietnam was not just a military failure—it was a narrative failure. This article examines how fear was cultivated, dissent fractured, and a nation led into a war that never needed to happen.

LinkedIn:

An anthropological examination of the Vietnam War as a case study in manufactured crisis, media conditioning, and the long-term consequences of domination-based decision-making.

Substack:

Why Vietnam still matters—and how its lessons were studied, refined, and reused. This is the first article in a series on war, narrative control, and historical memory.

SERIES: WAR AS STORY

Articles in this series:

- Vietnam: A War That Did Not Need to Happen

- Venezuela: The Political Economy of War

- When Disgust No Longer Stops War

- When the Faces Could Still Stop the War

Series closure:

Coda: When the Guardians Are Gone

A Passing of the Torch

🔔 SUBSCRIBE

About This Series

When War Is a Story examines the narratives that turn ambiguity into violence and repetition into consent — from Vietnam to the present.

If this work matters to you, please consider subscribing and sharing. Independent journalism survives through readers.

👉 Subscribe: https://substack.com/@janetalexlessinphd