EDWARD DE VERE (1550 – 1604)

by Janet Lessin

Updated November 8, 2025

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Lord Great Chamberlain of England

(believed by some to have authored the works attributed to William Shakespeare — my 13-times-removed first cousin)

Born: 12 April 1550 • Hedingham Castle, Essex, England

Died: 24 June 1604 • Hackney, Greater London, England

Biography

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was one of the most brilliant and controversial figures of the Elizabethan age. Born into one of England’s oldest noble families, he inherited the Oxford earldom at the age of twelve after the death of his father, John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford. His mother was Margery Golding.

As a royal ward of Queen Elizabeth I, young Edward was placed under the guardianship of her chief advisor, Sir William Cecil (later Lord Burghley), and educated in Cecil’s household among the elite of Tudor society. At twenty-one, he married Cecil’s daughter, Anne Cecil, cementing an alliance between ancient nobility and the rising power of Elizabeth’s court administrators.

Oxford became known for his wit, poetry, and patronage of the arts. He supported writers, actors, and musicians, and his household was a lively center of artistic innovation. Contemporaries praised him as a gifted lyric poet and dramatist. Yet his passionate temperament, costly tastes, and impulsive behavior led to repeated clashes at court and the gradual loss of much of his inherited fortune.

His marriage to Anne was stormy; they were estranged for several years, and Oxford initially denied paternity of their first child. Despite these difficulties, they had five children together, including Elizabeth Stanley, Countess of Derby, who became an important figure in the next generation of the English nobility. After Anne’s death in 1588, Oxford married Elizabeth Trentham in 1591, by whom he had a son, Henry de Vere, later the 18th Earl of Oxford.

Oxford’s later years were spent largely in retirement at his house in Hackney, where he died on 24 June 1604 at the age of 54.

Titles & Offices

- 17th Earl of Oxford (1562 – 1604)

- Viscount Bulbeck

- Lord Great Chamberlain of England

Family Connections

Parents: John de Vere (16th Earl of Oxford) and Margery Golding

Spouses: Anne Cecil (1556 – 1588); Elizabeth Trentham (m. 1591)

Children: Elizabeth Stanley (Countess of Derby), Lord Bulbeck, Bridget Norris (Countess of Berkshire), Lady Frances de Vere (d. young), Susan Herbert (Countess of Montgomery), Henry de Vere (18th Earl of Oxford), and Sir Edward Vere (illegitimate).

Legacy

Edward de Vere remains a captivating figure in both literary and historical circles. His brilliance, volatility, and deep engagement with the arts left an enduring mark on Elizabethan culture. For centuries, scholars and enthusiasts have debated whether he was the actual author of the works published under the name William Shakespeare—a theory that continues to inspire lively discussion.

To me, as a descendant, his life embodies the genius and turbulence of an era that forever shaped English literature and thought.

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford

Sir Edward De Vere (17th Earl of Oxford, Lord Great Chamberlain of England) (William Shakespeare) 1st cousin 13x removed)

1550–1604

BIRTH 12 APRIL 1550 • Castle Hedingham, Braintree District, Essex, England

DEATH 24 JUN 1604 • Hackney, London Borough of Hackney, Greater London, England1st cousin 13x removed

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Edward de Vere | |

|---|---|

| Earl of Oxford | |

| 17th-century portrait based on lost 1575 original, National Portrait Gallery, London | |

| Tenure | 1562–1604 |

| Other titles | Viscount Bulbeck |

| Born | 12 April 1550 Hedingham Castle, Essex, England |

| Died | 24 June 1604 (aged 54) Kings Place, Hackney |

| Nationality | English |

| Locality | Essex |

| Offices | Lord Great Chamberlain |

| Spouse(s) | Anne Cecil(m. 1571; died 1588)Elizabeth Trentham (m. 1591) |

| Issue | Elizabeth Stanley, Countess of DerbyLord BulbeckeBridget Norris, Countess of BerkshireLady Frances de Vere (died before age 3)Susan Herbert, Countess of MontgomeryHenry de Vere, 18th Earl of OxfordSir Edward Vere (illegitimate) |

| Parents | John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford Margery Golding |

| Signature |

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (/də ˈvɪər/; 12 April 1550 – 24 June 1604) was an English peer and courtier of the Elizabethan era. Oxford was heir to the second oldest earldom in the kingdom, a court favourite for a time, a sought-after patron of the arts, and noted by his contemporaries as a lyric poet and court playwright, but his volatile temperament precluded him from attaining any courtly or governmental responsibility and contributed to the dissipation of his estate.[1]

Edward de Vere was the only son of John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, and Margery Golding. After the death of his father in 1562, he became a ward of Queen Elizabeth I and was sent to live in the household of her principal advisor, Sir William Cecil. He married Cecil’s daughter, Anne, with whom he had five children.[2] Oxford was estranged from her for five years and refused to acknowledge he was the father of their first child.

A champion jouster, Oxford travelled widely throughout France and the many states of Italy. He was among the first to compose love poetry at the Elizabethan court[3] and was praised as a playwright, though none of the plays known as his survive.[4] A stream of dedications praised Oxford for his generous patronage of literary, religious, musical, and medical works,[5] and he patronised both adult and boy acting companies,[6] as well as musicians, tumblers, acrobats and performing animals.[7]

He fell out of favour with the Queen in the early 1580s and was exiled from court and briefly imprisoned in the Tower of London when his mistress Anne Vavasour, one of Elizabeth’s maids of honour, gave birth to his son in the palace. Vavasour, too, was incarcerated, and the affair instigated violent street brawls between Oxford and her kinsmen. He was reconciled to the Queen in May 1583 at Theobalds,[8] but all opportunities for advancement had been lost. In 1586, the Queen granted Oxford £1,000 annually ($483,607 in 2020 US dollars)[9] to relieve the financial distress caused by his extravagance and the sale of his income-producing lands for ready money. After the death of his first wife, Anne Cecil, Oxford married Elizabeth Trentham, one of the Queen’s maids of honour, with whom he had an heir, Henry de Vere. Oxford died in 1604, having spent the entirety of his inherited estates.

Since the 1920s, Oxford has been among the most prominent alternative candidates proposed for the authorship of Shakespeare’s works.

Family and childhood[edit]

The surviving keep of Hedingham Castle, the de Vere family seat since the Norman Conquest

Edward de Vere was born heir to the second-oldest extant earldom in England at the de Vere ancestral home, Hedingham Castle, in Essex, northeast of London. He was the only son of John de Vere, 16th Earl of Oxford, and his second wife, Margery Golding and was probably named to honour Edward VI, from whom he received a gilded christening cup.[10] He had an older half-sister, Katherine, the child of his father’s first marriage to Dorothy Neville,[11] and a younger sister, Mary de Vere.[12] Both his parents had established court connections: the 16th Earl accompanying Princess Elizabeth from her house arrest at Hatfield to the throne, and the countess being appointed a maid of honour in 1559.

Before his father’s death, Edward de Vere was styled Viscount Bulbeck, or Bolebec, and was raised in the Protestant reformed faith. Like many children of the nobility, he was raised by surrogate parents, in his case in the household of Sir Thomas Smith.[13] At eight he entered Queens’ College, Cambridge, as an impubes, or immature fellow-commoner, later transferring to St John’s. Thomas Fowle, a former fellow of St John’s College, Cambridge, was paid £10 annually as de Vere’s tutor.[14]

His father died on 3 August 1562, shortly after making his will.[15] Because he held lands from the Crown by knight service, his son became a royal ward of the Queen and was placed in the household of Sir William Cecil, her secretary of state and chief advisor.[16] At 12, de Vere had become the 17th Earl of Oxford, Lord Great Chamberlain of England, and heir to an estate whose annual income, though assessed at approximately £2,500, may have run as high as £3,500 (£1.25 million as of 2023).[17]

Wardship[edit]

William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, the Queen’s Secretary of State and de Vere’s father-in-law, c. 1571.

While living at the Cecil House, Oxford’s daily studies consisted of dancing instruction, French, Latin, cosmography, writing exercises, drawing, and common prayers. During his first year at Cecil House, he was briefly tutored by Laurence Nowell, the antiquarian and Anglo-Saxon scholar.[18] In a letter to Cecil, Nowell explains: “I clearly see that my work for the Earl of Oxford cannot be much longer required”, and his departure after eight months has been interpreted as either a sign of the thirteen-year-old Oxford’s intractability as a pupil, or an indication that his precocity surpassed Nowell’s ability to instruct him.[19] In May 1564 Arthur Golding, in his dedication to his Th’ Abridgement of the Histories of Trogus Pompeius, attributed to his young nephew an interest in ancient history and contemporary events.[20]

In 1563, Oxford’s older half-sister, Katherine, then Lady Windsor, challenged the legitimacy of the marriage of de Vere’s parents in the Ecclesiastical court. His uncle Golding argued that the Archbishop of Canterbury should halt the proceedings since a proceeding against a ward of the Queen could not be brought without prior licence from the Court of Wards and Liveries.[21]

Some time before October 1563, Oxford’s mother married secondly Charles Tyrrell, a Gentleman Pensioner.[22] In May 1565 she wrote to Cecil, urging that the money from family properties set aside by Oxford’s father’s will for his use during his minority should be entrusted to herself and other family friends, to protect it and to ensure that Oxford would be able to meet the expenses of furnishing his household and suing his livery when he reached his majority; this last would end his wardship, through cancelling his debt with the Court of Wards, and convey to him the powers attached to his titles.[23] There is no evidence that Cecil ever replied to her request. She died three years later, and was buried beside her first husband at Earls Colne. Oxford’s stepfather, Charles Tyrrell, died in March 1570.[24]

In August 1564 Oxford was among 17 noblemen, knights, and esquires in the Queen’s entourage who were awarded the honorary degree of Master of Arts by the University of Cambridge, and he was awarded another by the University of Oxford on a Royal progress in 1566. His future father-in-law, William Cecil, also received honorary degrees of Master of Arts on the same progresses.[25] There is no evidence that Oxford ever received a Bachelor of Arts degree. In February 1567 he was admitted to Gray’s Inn to study law.[26]

On 23 July 1567, while practising fencing in the backyard of Cecil House in the Strand, the seventeen-year-old Oxford killed Thomas Brincknell, an under-cook in the Cecil household. At the coroner‘s inquest the next day, the jury, which included Oxford’s servant, and Cecil’s protégé, the future historian Raphael Holinshed, found that Brincknell, drunk, had deliberately committed suicide by running onto Oxford’s blade. As a suicide, he was not buried in consecrated ground, and all his worldly possessions were confiscated, leaving his pregnant wife destitute. She delivered a stillborn child shortly after Brinknell’s death. Cecil later wrote that he attempted to have the jury find that Oxford had acted in self-defence.[27]

Records of books purchased for Oxford in 1569 attest to his continued interest in history, as well as literature and philosophy. Among them were editions of a gilt Geneva Bible, Chaucer, Plutarch, two books in Italian, and folio editions of Cicero and Plato.[28] In the same year Thomas Underdown dedicated his translation of the Æthiopian History of Heliodorus to Oxford, praising his ‘haughty courage’, ‘great skill’ and ‘sufficiency of learning’.[29] In the winter of 1570, Oxford made the acquaintance of the mathematician and astrologer John Dee and became interested in occultism, studying magic and conjuring.[30]

In 1569, Oxford received his first vote for membership in the Order of the Garter, but never attained the honour in spite of his high rank and office.[31] In November of that year, Oxford petitioned Cecil for a foreign military posting. Although the Roman Catholic Revolt of the Northern Earls had broken out that year, Elizabeth refused to grant the request.[32] Cecil eventually obtained a position for Oxford under the Earl of Sussex in a Scottish campaign the following spring. He and Sussex became staunch mutual supporters at court.[33]

Coming of age[edit]

Coat of Arms of Edward de Vere from George Baker’s The composition or making of the moste excellent and pretious oil called oleum magistrale (1574)

On 12 April 1571, Oxford attained his majority and took his seat in the House of Lords. Great expectations attended his coming of age; Sir George Buck recalled predictions that ‘he was much more like … to acquire a new erldome then to wast & lose an old erldom’, a prophecy that was never fulfilled.[34]

Although formal certification of his freedom from Burghley’s control was deferred until May 1572,[35] Oxford was finally granted the income of £666 which his father had intended him to have earlier, but properties set aside to pay his father’s debts would not come his way for another decade. During his minority as the Queen’s ward, one-third of his estate had already reverted to the Crown, much of which Elizabeth had long since settled on Robert Dudley. Elizabeth demanded a further payment of £3,000 for overseeing the wardship and a further £4,000 for suing his livery. Oxford pledged double the amount if he failed to pay when it fell due, effectively risking a total obligation of £21,000.[36]

By 1571, Oxford was a court favourite of Elizabeth’s. In May, he participated in the three-day tilt, tourney and barrier at which, although he did not win, he was given chief honours in celebration of the attainment of his majority, his prowess winning admiring comments from spectators.[37] In August, Oxford attended Paul de Foix, who had come to England to negotiate a marriage between Elizabeth and the Duke of Anjou, the future King Henry III of France.[38] His published poetry dates from this period and, along with Edward Dyer he was one of the first courtiers to introduce vernacular verse to the court.[39]

Marriage[edit]

The Royal Palace of Whitehall where the Earl of Oxford married Anne Cecil, as it appeared about 100 years later

In 1562, the 16th Earl of Oxford had contracted with Henry Hastings, 3rd Earl of Huntingdon, for his son Edward to marry one of Huntingdon’s sisters; when he reached the age of eighteen, he was to choose either Elizabeth or Mary Hastings. However, after the death of the 16th Earl, the indenture was allowed to lapse. Elizabeth Hastings later married Edward Somerset, while Mary Hastings died unmarried.[citation needed]

In the summer of 1571, Oxford declared an interest in Cecil’s 14 year-old daughter,[citation needed] Anne, and received the queen’s consent to the marriage. Anne had been pledged to Philip Sidney two years earlier, but after a year of negotiations Sidney’s father, Sir Henry, was declining in the Queen’s favour and Cecil suspected financial difficulties. In addition, Cecil had been elevated to the peerage as Lord Burghley in February 1571, thus elevating his daughter’s rank, so the negotiations were cancelled.[citation needed] Cecil was displeased with the arrangement, given his daughter’s age compared to Oxford’s, and had entertained the idea of marrying her to the Earl of Rutland instead.[40] The marriage was deferred until Anne was fifteen and finally took place at the Palace of Whitehall on 16 December 1571, in a triple wedding with that of Lady Elizabeth Hastings and Edward Somerset, Lord Herbert, and Edward Sutton, 4th Baron Dudley and bride, Mary Howard,[41] with the Queen in attendance. The tying of two young English noblemen of great fortune into Protestant families was not lost on Elizabeth’s Catholic enemies.[42][clarification needed] Burghley gave Oxford for his daughter’s dowry land worth £800, and a cash settlement of £3,000. This amount was equal to Oxford’s livery fees and was probably intended to be used as such, but the money vanished without a trace.[43]

Oxford assigned Anne a jointure of some £669,[44] but even though he was of age and a married man, he was still not in possession of his inheritance. After finally paying the Crown the £4,000 it demanded for his livery, he was finally licensed to enter on his lands in May 1572.[45] He was entitled to yearly revenues from his estates and the office of Lord Great Chamberlain of approximately £2,250, but he was not entitled to the income from his mother’s jointure until after her death, nor to the income from certain estates set aside until 1583 to pay his father’s debts. In addition, the fines assessed against Oxford in the Court of Wards for his wardship, marriage, and livery already totalled some £3,306. To guarantee payment, he entered into bonds to the Court totalling £11,000, and two further private bonds for £6,000 apiece.[46]

In 1572, Oxford’s first cousin and closest relative, the Duke of Norfolk, was found guilty of a Catholic conspiracy against Elizabeth and was executed for treason. Oxford had earlier petitioned both the Queen and Burghley on the condemned Norfolk’s behalf, to no avail, and it was claimed in a “murky petition from an unidentified woman” that he had plotted to provide a ship to assist his cousin’s escape attempt to Spain.[47]

The following summer, Oxford planned to travel to Ireland; at this point, his debts were estimated at a minimum of £6,000.[48]

In the summer of 1574, Elizabeth admonished Oxford “for his unthriftyness”, and on 1 July he bolted to the continent without permission, travelling to Calais with Lord Edward Seymour, and then to Flanders, “carrying a great sum of money with him”. Coming as it did during a time of expected hostilities with Spain, Mary, Queen of Scots, interpreted his flight as an indication of his Catholic sympathies, as did the Catholic rebels then living on the continent. Burghley, however, assured the queen that Oxford was loyal, and she sent two Gentlemen Pensioners to summon him back, under threat of heavy penalties. Oxford returned to England by the end of the month and was in London on the 28th. His request for a place on the Privy Council was rejected, but the queen’s anger was abated and she promised him a licence to travel to Paris, Germany, and Italy on his pledge of good behaviour.[49]

Foreign travel[edit]

In January 1575 Elizabeth issued a licence to Oxford to travel, and provided him with letters of introduction to foreign monarchs.[50] Prior to his departure, he entered into two indentures. In the first contract, he sold his manors in Cornwall, Staffordshire and Wiltshire to three trustees for £6,000. In the second, to prevent his estates passing by default to his sister Mary in the event of his dying abroad without heirs, he entailed the lands of the earldom on his first cousin, Hugh Vere. The indenture also provided for payment of debts amounting to £9,096, £3,457 of which was still owed to the Queen as expenses for his wardship.[51]

Oxford left England in the first week of February 1575, and a month later was presented to the King and Queen of France. News that his new wife, Anne, was pregnant had reached him in Paris, and he sent her many extravagant presents in the coming months. But somewhere along the way, his mind was poisoned against Anne and the Cecils, and he became convinced that the expected child was not his. The elder Cecils loudly voiced their outrage at the rumours, which probably worsened the situation.[52] In mid-March he travelled to Strasbourg, and then made his way to Venice, via Milan.[53] Although his daughter, Elizabeth, was born at the beginning of July, for unexplained reasons Oxford did not learn of her birth until late September.[54]

Oxford remained in Italy for a year, during which he was evidently captivated by Italian fashions in clothing, jewellery and cosmetics. He is recorded by John Stow as having introduced various Italian luxury items to the English court which immediately became fashionable, such as embroidered or trimmed scented gloves. Elizabeth had a pair of decorated gloves scented with perfume that for many years was known as the “Earl of Oxford’s perfume”.[55] Lacking evidence, his interest in higher Italian culture, its literature, music and visual art, is less sure. His only recorded judgement about the country itself was unenthusiastic. In a letter to Burghley he wrote, “…for my lekinge of Italy, my lord I am glad I haue sene it, and I care not euer to see it any more vnles it be to serue my prince or contrie.”[56]

In January 1576 Oxford wrote to Lord Burghley from Siena about complaints that had reached him about his creditors’ demands, which included the Queen and his sister, and directing that more of his land be sold to pay them.[57] He left Venice in March, intending to return home by way of Lyons and Paris; although one later report has him as far south as Palermo in Sicily.[58] At this point the Italian financier Benedict Spinola had lent Oxford over £4,000 for his 15-month-long continental tour, while in England over a hundred tradesmen were seeking settlement of debts totalling thousands of pounds.[59]

On Oxford’s return across the Channel in April 1576, his ship was seized by pirates from Flushing, who took his possessions, stripped him to his shirt, and might have murdered him had not one of them recognized him.[60]

On his return, Oxford refused to live with his wife and took rooms at Charing Cross. Aside from the unspoken suspicion that Elizabeth was not his child, Burghley’s papers reveal a flood of bitter complaints by Oxford against the Cecil family.[61] Upon the Queen’s request, he allowed his wife to attend the Queen at court, but only when he was not present, and he insisted that she not attempt to speak to him. He also stipulated that Burghley must make no further appeals to him on Anne’s behalf.[62] He was estranged from Anne for five years.

In February 1577 it was rumoured that Oxford’s sister Mary would marry Lord Gerald Fitzgerald (1559–1580), but by 2 July her name was linked with that of Peregrine Bertie, later Lord Willoughby d’Eresby. Bertie’s mother, the Duchess of Suffolk, wrote to Lord Burghley that “my wise son has gone very far with my Lady Mary Vere, I fear too far to turn”. Both the Duchess and her husband Richard Bertie first opposed the marriage, and the Queen initially withheld her consent. Oxford’s own opposition to the match was so vehement that for some time Mary’s prospective husband feared for his life.[63] On 15 December the Duchess of Suffolk wrote to Burghley describing a plan she and Mary had devised to arrange a meeting between Oxford and his daughter.[64] Whether the scheme came to fruition is unknown. Mary and Bertie were married sometime before March of the following year.[65]

Quarrels, plots and scandals[edit]

Oxford had sold his inherited lands in Cornwall, Staffordshire, and Wiltshire prior to his continental tour. On his return to England in 1576 he sold his manors in Devonshire; by the end of 1578 he had sold at least seven more.[66]

In 1577 Oxford invested £25 in the second of Martin Frobisher‘s expeditions in search of the Northwest Passage.[67] In July 1577, he asked the Crown for the grant of Castle Rising, which had been forfeited to the Crown due to his cousin Norfolk’s attainder in 1572.[68] As soon as it was granted to him, he sold it, along with two other manors, and sank some £3,000 into Frobisher’s third expedition.[69] The ‘gold’ ore brought back turned out to be worthless, and Oxford lost the entire investment.[70]

In the summer of 1578, Oxford attended the Queen’s progress through East Anglia.[71] The royal party stayed at Lord Henry Howard’s residence at Audley End. A contretemps occurred during the progress in mid-August when the Queen twice asked Oxford to dance before the French ambassadors, who were in England to negotiate a marriage between the 46-year-old English queen and the younger brother of Henri III of France, the 24 year-old Duke of Anjou. Oxford refused, on the grounds that he “would not give pleasure to Frenchmen”.[72]

In April 1578, the Spanish ambassador, Bernardino de Mendoza, had written to King Philip II of Spain that it had been proposed that if Anjou were to travel to England to negotiate his marriage to the Queen, Oxford, Surrey, and Windsor should be hostages for his safe return.[73] Anjou himself did not arrive in England until the end of August, but his ambassadors were already in England. Oxford was sympathetic to the proposed marriage; Leicester and his nephew Philip Sidney were adamantly opposed to it. This antagonism may have triggered the famous quarrel between Oxford and Sidney on the tennis court at Whitehall. It is not entirely clear who was playing on the court when the fight erupted; what is undisputed is that Oxford called Sidney a ‘puppy’, while Sidney responded that “all the world knows puppies are gotten by dogs, and children by men”. The French ambassadors, whose private galleries overlooked the tennis court, were witness to the display. Whether it was Sidney who next challenged Oxford to a duel or the other way around, the matter was not taken further, and the Queen personally took Sidney to task for not recognizing the difference between his status and Oxford’s. Christopher Hatton and Sidney’s friend Hubert Languet also tried to dissuade Sidney from pursuing the matter, and it was eventually dropped.[74] The specific cause is not known, but in January 1580 Oxford wrote and challenged Sidney; by the end of the month Oxford was confined by the Queen to his chambers, and was not released until early February.[75]

Oxford openly quarrelled with the Earl of Leicester at about this time; he was confined to his chamber at Greenwich for some time ‘about the libelling between him and my Lord of Leicester’.[76] In the summer of 1580, Gabriel Harvey, apparently motivated by a desire to ingratiate himself with Leicester,[77] satirized Oxford’s love for things Italian in verses entitled Speculum Tuscanismi and in Three Proper and Witty Familiar Letters.[78]

Although details are unclear, there is evidence that in 1577 Oxford attempted to leave England to see service in the French Wars of Religion on the side of King Henry III.[79] Like many members of older established aristocratic families in England, he inclined to Roman Catholicism; and after his return from Italy, he was reported to have embraced the religion, perhaps after a distant kinsman, Charles Arundell, introduced him to a seminary priest named Richard Stephens.[80] But just as quickly, by late in 1580 he had denounced a group of Catholics, among them Arundell, Francis Southwell, and Henry Howard, for treasonous activities and asking the Queen’s mercy for his own, now repudiated, Catholicism.[81] Elizabeth characteristically delayed in acting on the matter and Oxford was detained under house arrest for a short time.[82]

Queen Elizabeth I. The so-called Phoenix Portrait, c. 1575

Leicester is credited by author Alan H. Nelson with having “dislodged Oxford from the pro-French group”, i.e., the group at court which favoured Elizabeth’s marriage to the Duke of Anjou. The Spanish ambassador, Mendoza, was also of the view that Leicester was behind Oxford’s informing on his fellow Catholics in an attempt to prevent the French marriage.[83] Peck concurs, stating that Leicester was “intent upon rendering Sussex’s allies politically useless”.[84][85]

The Privy Council ordered the arrest of both Howard and Arundel; Oxford immediately met secretly with Arundell to convince him to support his allegations against Howard and Southwell, offering him money and a pardon from the Queen.[86] Arundell refused this offer, and he and Howard initially sought asylum with Mendoza. Only after being assured that they would be placed under house arrest in the home of a Privy Councillor, did the pair give themselves up.[87] During the first weeks after their arrest they pursued a threefold strategy: they would admit to minor crimes, attempt to prove Oxford a liar by his offers of money to testify to his accusations, and try to demonstrate that their accuser posed the real danger to the Crown.[88] Their allegations against Oxford included atheism, lying, heresy, disobedience to the crown, treason, murder for hire, sexual perversion, habitual drunkenness, vowing to murder various courtiers, and criticizing the Queen for doing “everything with the worst grace that ever woman did.”[89]

Most seriously, Howard and Arundell charged Oxford with serial child rape, claiming he’d abused “so many boyes it must nedes come out.”[10] Detailed testimony from nearly a dozen victims and witnesses substantiated the charge and included names, dates, and places. Two of the six boys named had sought help from adults after Oxford raped them violently and denied them medical care. A young cook named Powers reported being subjected to multiple assaults at Hampton Court in the winter of 1577-78, at Whitehall, and in Oxford’s Broad Street home.[10] Orazio Coquo’s account is well documented outside the Howard-Arundel report. In testimony to the Venetian Inquisition dated 27 August 1577, Coquo explained that he was singing in the choir at Venice’s Santa Maria Formosa on 1 March 1576 when Oxford invited him to work in England as his page. Then 15, the boy sought his parents’ advice and departed Venice just 4 days later.[11] Coquo arrived with Oxford in Dover on 20 April 1576 and fled 11 months later on 20 March 1577,[15] aided by a Milanese merchant who gave him 25 ducats for the journey: He “told me that I would be corrupted if I remained,” Orazio testified, “and he didn’t want me to stay there any longer.” When asked whether he sought Oxford’s permission before leaving, the boy replied, “Sirs, no, because he would not have allowed me to leave.”[15]

Arundell and Howard cleared themselves of Oxford’s accusations, although Howard remained under house arrest into August, while Arundell was not freed until October or November. None of the three was ever indicted or tried.[90] Neither Arundell nor Howard ever returned to court favour, and after the Throckmorton Plot of 1583 in support of Mary, Queen of Scots, Arundell fled to Paris with Thomas, Lord Paget, the elder brother of the conspirator Charles Paget. In the meantime, Oxford won a tournament at Westminster on 22 January. His page’s speech at the tournament, describing Oxford’s appearance as the Knight of the Tree of the Sun, was published in 1592 in a pamphlet entitled Plato, Axiochus.[91]

On 14 April 1589 Oxford was among the peers who found Philip Howard, Earl of Arundel, the eldest son and heir of Oxford’s cousin, Thomas, Duke of Norfolk, guilty of treason;[92] Arundel later died in prison. Oxford later insisted that “the Howards were the most treacherous race under heaven” and that “my Lord Howard [was] the worst villain that lived in this earth.”[93]

During the early 1580s, it is likely that the Earl of Oxford lived mainly at one of his Essex country houses, Wivenhoe, which was sold in 1584. In June 1580 he purchased a tenement and seven acres of land near Aldgate in London from the Italian merchant Benedict Spinola for £2,500. The property, located in the parish of St Botolphs, was known as the Great Garden of Christchurch and had formerly belonged to Magdalene College, Cambridge.[94] He also purchased a London residence, a mansion in Bishopsgate known as Fisher’s Folly. According to Henry Howard, Oxford paid a large sum for the property and renovations to it.[95]

Anne Vavasour, maid of honour to Elizabeth I, mother of de Vere’s illegitimate son

On 23 March 1581 Sir Francis Walsingham advised the Earl of Huntingdon that two days earlier Anne Vavasour, one of the Queen’s maids of honour, had given birth to a son, and that “the Earl of Oxford is avowed to be the father, who hath withdrawn himself with intent, as it is thought, to pass the seas”. Oxford was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower of London, as was Anne and her infant, who would later be known as Sir Edward Vere.[96] Burghley interceded for Oxford, and he was released from the Tower on 8 June, but he remained under house arrest until some time in July.[97]

While Oxford was under house arrest in May, Thomas Stocker dedicated to him his Divers Sermons of Master John Calvin, stating in the dedication that he had been “brought up in your Lordship’s father’s house”.[98]

Oxford was still under house arrest in mid-July,[99] but took part in an Accession Day tournament at Whitehall on 17 November 1581.[100] He was then banished from court until June 1583. He appealed to Burghley to intervene with the Queen on his behalf, but his father-in-law repeatedly put the matter in the hands of Sir Christopher Hatton.[citation needed]

At Christmas 1581, Oxford was reconciled with his wife, Anne,[101] but his affair with Anne Vavasour continued to have repercussions. In March 1582 there was a skirmish in the streets of London between Oxford and Anne’s uncle, Sir Thomas Knyvet. Oxford was wounded, and his servant killed; reports conflict as to whether Kynvet was also injured.[102] There was another fray between Knyvet’s and Oxford’s retinues on 18 June, and a third six days later, when it was reported that Knyvet had “slain a man of the Earl of Oxford’s in fight”.[103] In a letter to Burghley three years later Oxford offered to attend his father-in-law at his house “as well as a lame man might”;[104] it is possible his lameness was a result of injuries from that encounter. On 19 January 1585 Anne Vavasour’s brother Thomas sent Oxford a written challenge; it appears to have been ignored.[105]

Meanwhile, the street brawling between factions continued. Another of Oxford’s men was killed in January,[106] and in March Burghley wrote to Sir Christopher Hatton about the death of one of Knyvet’s men, thanking Hatton for his efforts “to bring some good end to these troublesome matters betwixt my Lord Oxford and Mr Thomas Knyvet”.[107]

On 6 May 1583, eighteen months after their reconciliation, Edward and Anne’s only son was born, but died the same day. The infant was buried at Castle Hedingham three days later.[108]

After intervention by Burghley and Sir Walter Raleigh, Oxford was reconciled to the Queen, and his two-year exile from court ended at the end of May on condition of his guarantee of good behaviour.[109] However, he never regained his position as a courtier of the first magnitude.[110]

Theatrical enterprises[edit]

The previous Earl of Oxford had maintained a company of players known as Oxford’s Men, which was discontinued by the 17th Earl two years after his father’s death.[111] Beginning in 1580, Oxford patronised both adult and boy companies and a company of musicians, and also sponsored performances by tumblers, acrobats, and performing animals.[112] The new Oxford’s Men toured the provinces between 1580 and 1587. Sometime after November 1583, Oxford bought a sublease of the premises used by the boy companies in the Blackfriars, and then gave it to his secretary, the writer John Lyly. Lyly installed Henry Evans, a Welsh scrivener and theatrical affectionado, as the manager of the new company of Oxford’s Boys, composed of the Children of the Chapel and the Children of Paul’s, and turned his talents to playwriting until the end of June 1584, when the original playhouse lease was voided by its owner.[113] In 1584–1585, “the Earl of Oxford’s musicians” received payments for performances in the cities of Oxford and Barnstaple. Oxford’s Men (also known as Oxford’s Players) stayed active until 1602.[citation needed]

Royal annuity[edit]

On 6 April 1584, Oxford’s daughter Bridget was born,[114] and two works were dedicated to him, Robert Greene’s Gwydonius; The Card of Fancy, and John Southern’s Pandora. Verses in the latter work mention Oxford’s knowledge of astronomy, history, languages, and music.[115]

Oxford’s financial situation was steadily deteriorating. At this point, he had sold almost all his inherited lands, which cut him off from what had been his principal source of income.[116] Moreover, because the properties were security for his unpaid debt to the Queen in the Court of Wards, he had had to enter into a bond with the purchaser, guaranteeing that he would indemnify them if the Queen were to make a claim against the lands to collect on the debt.[117] To avoid this eventuality, the purchasers of his estates agreed to pay Oxford’s debt to the Court of Wards in installments.[118]

In 1585 negotiations were underway for King James VI of Scotland to come to England to discuss the release of his mother, Mary, Queen of Scots, and in March Oxford was to be sent to Scotland as one of the hostages for James’s safety.[119]

In 1586, Oxford petitioned the Queen for an annuity to relieve his distressed financial situation. His father-in-law made him several large loans, and Elizabeth granted him a £1,000 annuity, to be continued at her pleasure or until he could be provided for otherwise. This annuity was later continued by James I.[120] De Vere’s widow, Elizabeth, petitioned James I for an annuity of £250 on behalf of her 11-year-old son, Henry, to continue the £1,000 annuity granted to de Vere. Henry was ultimately awarded a £200 annuity for life.[121] James I would continue the grant after her death.[10]

Another daughter, Susan, was born on 26 May 1587. On 12 September, another daughter, Frances, is recorded as buried at Edmonton. Her birthdate is unknown; presumably, she was between one and three years of age.[122]

In July Elizabeth granted the Earl property which had been seized from Edward Jones, who had been executed for his role in the Babington Plot. In order to protect the land from Oxford’s creditors, the grant was made in the name of two trustees.[123] At the end of November it was agreed that the purchasers of Oxford’s lands would pay his entire debt of some £3,306 due to the Court of Wards over a five-year period, finishing in 1592.[122]

In July and August 1588 England was threatened by the Spanish Armada. On 28 July Leicester, who was in overall command of the English land troops, asked for instructions regarding Oxford, stating that “he seems most willing to hazard his life in this quarrel”.[124] The Earl was offered the governorship of the port of Harwich, but he thought it was unworthy and declined the post; Leicester was glad to be rid of him.[125]

In December 1588 Oxford had secretly sold his London mansion Fisher’s Folly to Sir William Cornwallis;[126] by January 1591 the author Thomas Churchyard was dealing with rent owing for rooms he had taken in a house on behalf of his patron.[127] Oxford wrote to Burghley outlining a plan to purchase the manorial lands of Denbigh, in Wales, if the Queen would consent, offering to pay for them by commuting his £1,000 annuity and agreeing to abandon his suit to regain the Forest of Essex (Waltham Forest), and to deed over his interests in Hedingham and Brets for the use of his children, who were living with Burghley under his guardianship.[128]

In the spring of 1591, the plan for the purchasers of his land to discharge his debt to the Court of Wards was disrupted by the Queen’s taking extents, or writs allowing a creditor to temporarily seize a debtor’s property.[129] Oxford complained that his servant Thomas Hampton had taken advantage of these writs by taking money from the tenants for his own use, and had also conspired with another of his servants to pass a fraudulent document under the Great Seal of England.[130] The Lord Mayor, Thomas Skinner, was also involved.[129] In June, Oxford wrote to Burghley reminding him that he had made an agreement with Elizabeth to relinquish his claim to the Forest of Essex for three reasons, one of which was the Queen’s reluctance to punish Skinner’s felony, which had caused Oxford to forfeit £20,000 in bonds and statutes.[131]

In 1586 Angel Day dedicated The English Secretary, the first epistolary manual for writing model letters in English, to Oxford,[132] and William Webbe praised him as “most excellent among the rest” of our poets in his Discourse of English Poetry.[133] In 1588 Anthony Munday dedicated to Oxford the two parts of his Palmerin d’Oliva.[134] The following year The Arte of English Poesie, attributed to George Puttenham, placed Oxford among a “crew” of courtier poets;[135] Puttenham also considered him among the best comic playwrights of the day.[136] In 1590 Edmund Spenser addressed to Oxford the third of seventeen dedicatory sonnets which preface The Faerie Queene, celebrating his patronage of poets.[137][138] The composer John Farmer, who was in Oxford’s service at the time, dedicated The First Set of Divers & Sundry Ways of Two Parts in One to him in 1591, noting in the dedication his patron’s love of music.[139]

Remarriage and later life[edit]

Elizabeth de Vere, who married William Stanley, the 6th Earl of Derby, in January 1594/1595, at the Royal Court at Greenwich

On 5 June 1588 Oxford’s wife Anne Cecil died at court of a fever; she was 31.[140]

On 4 July 1591 Oxford sold the Great Garden property at Aldgate to John Wolley and Francis Trentham.[141] The arrangement was stated to be for the benefit of Francis’s sister, Elizabeth Trentham, one of the Queen’s Maids of Honour, whom Oxford married later that year. On 24 February 1593, at Stoke Newington, she gave birth to his only surviving son, Henry de Vere, who was his heir.[142]

Between 1591 and 1592 Oxford disposed of the last of his large estates; Castle Hedingham, the seat of his earldom, went to Lord Burghley; it was held in trust for Oxford’s three daughters by his first marriage.[143] He commissioned his servant, Roger Harlakenden, to sell Colne Priory. Harlekenden contrived to undervalue the land, then purchase it (as well as other parcels that were not meant to be sold) under his son’s name;[144] the suits Oxford brought against Harlakenden for fraud dragged out for decades and were never settled in his lifetime.[145]

Protracted negotiations to arrange a match between his daughter Elizabeth and Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, did not result in marriage; on 19 November 1594, six weeks after Southampton turned 21, ‘the young Earl of Southampton, refusing the Lady Vere, payeth £5000 of present money’.[146] In January Elizabeth married William Stanley, 6th Earl of Derby.[147] Derby had promised Oxford his new bride would have £1,000 a year, but the financial provision for her was slow in materializing.[148]

His father-in-law, Lord Burghley, died on 4 August 1598 at the age of 78, leaving substantial bequests to Oxford’s two unmarried daughters, Bridget and Susan.[149] The bequests were structured to prevent Oxford from gaining control of his daughters’ inheritances by assuming custody of them.[150]

Earlier negotiations for a marriage to William Herbert having fallen through, in May or June 1599 Oxford’s 15 year-old daughter Bridget married Francis Norris.[151] Susan married Philip Herbert, 4th Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery.[152]

From March to August 1595 Oxford actively importuned the Queen, in competition with Lord Buckhurst, to farm the tin mines in Cornwall.[153] He wrote to Burghley, enumerating years of fruitless attempts to amend his financial situation and complained: ‘This last year past I have been a suitor to her Majesty that I might farm her tins, giving £3000 a year more than she had made.’[154] Oxford’s letters and memoranda indicate that he pursued his suit into 1596, and renewed it again three years later, but was ultimately unsuccessful in obtaining the tin monopoly.[155]

In October 1595, Oxford wrote to his brother-in-law, Sir Robert Cecil, of friction between himself and the ill-fated Earl of Essex, partly over his claim to property, terming him ‘the only person that I dare rely upon in the court’. Cecil seems to have done little to further Oxford’s interests in the suit.[156]

In March he was unable to go to court due to illness, in August he wrote to Burghley from Byfleet, where he had gone for his health: ‘I find comfort in this air, but no fortune in the court.’[157] In September, he again wrote of ill health, regretting he had not been able to pay attendance to the Queen. Two months later Rowland Whyte wrote to Sir Robert Sidney that ‘Some say my Lord of Oxford is dead’.[158] Whether the rumour of his death was related to the illness mentioned in his letters earlier in the year is unknown. Oxford attended his last Parliament in December, perhaps another indication of his failing health.[159]

On 28 April 1599 Oxford was sued by the widow of his tailor for a debt of £500 for services rendered some two decades earlier. He claimed that not only had he paid the debt, but that the tailor had absconded with ‘cloth of gold and silver and other stuff’ belonging to him, worth £800. The outcome of the suit is unknown.[160]

In July 1600 Oxford wrote requesting Sir Robert Cecil’s help in securing an appointment as Governor of the Isle of Jersey, once again citing the Queen’s unfulfilled promises to him.[161] In February he again wrote for his support, this time for the office of President of Wales.[162] As with his former suits, Oxford was again unsuccessful; during this time he was listed on the Pipe rolls as owing £20 for the subsidy.[163]

After the abortive Essex rebellion in February 1601, Oxford was ‘the senior of the twenty-five noblemen’ who rendered verdicts at the trials of Essex and Southampton for treason.[164] After Essex’s co-conspirator Sir Charles Danvers was executed in March, Oxford became a party to a complicated suit regarding lands which had reverted to the Crown by escheat at Danvers’s attainder, a suit opposed by Danvers’s kinsmen.[165] De Vere continued to suffer from ill health, which kept him from court.[166] On 4 December, Oxford was shocked that Cecil, who had encouraged him to undertake the Danvers suit on the Crown’s behalf, had now withdrawn his support for it.[167] As with all his other suits aimed at improving his financial situation, this last of Oxford’s suits to the Queen ended in disappointment.[23]

Last years[edit]

In the early morning of 24 March 1603, Queen Elizabeth died without naming a successor. A few days beforehand, at his house at Hackney, Oxford had entertained the Earl of Lincoln, a nobleman known for erratic and violent behaviour similar to his host’s.[168] Lincoln reported that after dinner Oxford spoke of the Queen’s impending death, claiming that the peers of England should decide the succession, and suggested that since Lincoln had ‘a nephew of the blood royal … Lord Hastings‘, he should be sent to France to find allies to support this claim.[169] Lincoln relayed this conversation to Sir John Peyton, Lieutenant of the Tower, who, knowing how physically and financially infirm Oxford was, refused to take Lincoln’s report as a serious threat to King James’s accession.[170]

Oxford expressed his grief at the late Queen’s death, and his apprehension for the future.[171] These fears were unfounded; in letters to Cecil in May and June 1603 he again pressed his decades-long claim to have Waltham Forest (Forest of Essex) and the house and park of Havering restored to him, and on 18 July the new King granted his suit.[172] On 25 July, Oxford was among those who officiated at the King’s coronation,[173] and a month later James confirmed his annuity of £1,000.[174]

Long weakened by poor health, Oxford passed custody of the Forest of Essex to his son-in-law Francis Norris and his cousin Sir Francis Vere on 18 June 1604. He died on 24 June of unknown causes at King’s Place, Hackney, and was buried on 6 July in the Hackney churchyard of St Augustine’s (now the parish of St. John-at-Hackney).[175] Oxford’s death passed without public or private notice. His grave was still unmarked on 25 November 1612 when his widow Elizabeth Trentham signed her will. She asked “to be buried in the Church of Hackney within the Countie of Middlesex, as neare vnto [unto] the bodie of my said late deare and noble lorde and husband as may bee,” and she requested that “there bee in the said Church erected for vs [us] a tombe fittinge our degree.”[176] The 18th Earl of Oxford failed to fulfil his mother’s request, and the location of his parents’ graves has been lost to time.

The absence of a grave marker and an unpublished manuscript written fifteen years after Oxford’s death have led to questions regarding his burial place. Documentary records including the Hackney registers and the will of de Vere’s widow (1612) confirm that he was buried in the church of St Augustine on 4 July 1604. One register lists “Edward Veare earl of Oxford” among burials; the other reads, “Edward deVeare Erle of Oxenford was buryed the 6th daye of Iulye Anno 1604.”[176][177] A manuscript history of the Vere family (c. 1619) written by Oxford’s first cousin, Percival Golding (1579-1635), raises the possibility of a re-interment sometime between 1612 and 1619 at Westminster Abbey:

He was a man in minde and body absolutely accomplished with honourable endowments. He died at his house at Hackney in the moneth of June Ao 1604 and lieth buryed at Westminster[178][179]

The same manuscript further suggests that de Vere enjoyed an honorary stewardship of the Privy Council in the last year of his life. While Nelson disputes his membership on the Council, de Vere’s signature appears on a letter dated 8 April 1603 from the Privy Council to the Lord High Treasurer of England[176][180]

Literary reputation[edit]

Eight poems by the Earl of Oxford were published in The Paradise of Dainty Devises (1576)

Oxford’s manuscript verses circulated widely in courtly circles. Three of his poems, “When wert thou born desire”, “My mind to me a kingdom is”, and “Sitting alone upon my thought”, are among the texts that repeatedly appear in the surviving 16th-century manuscript miscellanies and poetical anthologies.[181] His earliest published poem was “The labouring man that tills the fertile soil” in Thomas Bedingfield‘s translation of Cardano‘s Comforte (1573). Bedingfield’s dedication to Oxford is dated 1 January 1572. In addition to his poem, Oxford also contributed a commendatory letter setting forth the reasons why Bedingfield should publish the work. In 1576 eight of his poems were published in the poetry miscellany The Paradise of Dainty Devises. According to the introduction, all the poems in the collection were meant to be sung, but Oxford’s were almost the only genuine love songs in the collection.[182] Oxford’s “What cunning can express” was published in The Phoenix Nest (1593) and republished in England’s Helicon (1600). “Who taught thee first to sigh alas my heart” appeared in The Teares of Fancie (1593). Brittons Bowre of Delight (1597) published “If women could be fair and yet not fond” under Oxford’s name, but the attribution today is not considered certain.[183]

Contemporary critics praised Oxford as a poet and a playwright. William Webbe names him as “the most excellent” of Elizabeth’s courtier poets.[184] Puttenham’s The Arte of English Poesie (1589), places him first on a list of courtier poets and includes an excerpt from “When wert thou born desire” as an example of “his excellance and wit”.[184] Puttenham also says that “highest praise” should be given to Oxford and Richard Edwardes for “Comedy and Enterlude”.[184] Francis Meres‘ Palladis Tamia (1598) names Oxford first of 17 playwrights listed by rank who are “the best for comedy amongst us”, and he also appears first on a list of seven Elizabethan courtly poets “who honoured Poesie with their pens and practice” in Henry Peacham‘s 1622 The Compleat Gentleman.[184]

Steven W. May writes that the Earl of Oxford was Elizabeth’s “first truly prestigious courtier poet … [whose] precedent did at least confer genuine respectability upon the later efforts of such poets as Sidney, Greville, and Raleigh.”[185] He describes de Vere as a “competent, fairly experimental poet working in the established modes of mid-century lyric verse” and his poetry as “examples of the standard varieties of mid-Elizabethan amorous lyric”.[186] May says that Oxford’s youthful love lyrics, which have been described as experimental and innovative, “create a dramatic break with everything known to have been written at the Elizabethan court up to that time” by virtue of being lighter in tone and metre and more imaginative and free from the moralizing tone of the courtier poetry of the “drab” age, which tended to be occasional and instructive.[187] and describes one poem, in which the author cries out against “this loss of my good name”, as a “defiant lyric without precedent in English Renaissance verse”.[182]

| Loss of Good Name Excerpt from The Paradise of Dainty Devises (1576) Framed in the front of forlorn hope, past all recovery, I stayless stand to abide the shock of shame and infamy. My life through lingering long is lodged, in lair of loathsome ways, My death delayed to keep from life, the harm of hapless days; My spirits, my heart, my wit and force, in deep distress are drowned, The only loss of my good name, is of these griefs the ground.Earl of Oxford, before 1576 |

May says that Oxford’s poetry was “one man’s contribution to the rhetorical mainstream of an evolving Elizabethan poetic” indistinguishable from “the output of his mediocre mid-century contemporaries”.[188] However, C. S. Lewis wrote that his poetry shows “a faint talent”, but is “for the most part undistinguished and verbose.”[189] Nelson says that “contemporary observers such as Harvey, Webbe, Puttenham, and Meres clearly exaggerated de Vere’s talent in deference to his rank. By any measure, his poems pale in comparison with those of Sidney, Lyly, Spenser, Shakespeare, Donne, and Jonson.” He says that his known poems are “astonishingly uneven” in quality, ranging from the “fine” to the “execrable”.[190]

Oxford was sought after for his literary and theatrical patronage; between 1564 and 1599, twenty-eight works were dedicated to him by authors, including Arthur Golding, John Lyly, Robert Greene, and Anthony Munday.[5] Of his 33 dedications, 13 appeared in original or translated works of literature, a higher percentage of literary works than other patrons of similar means. His lifelong patronage of writers, musicians, and actors prompted May to term Oxford “a nobleman with extraordinary intellectual interests and commitments”, whose biography exhibits a “lifelong devotion to learning”.[191] He goes on to say that “Oxford’s genuine commitment to learning throughout his career lends a necessary qualification to Stone’s conclusion that de Vere simply squandered the more than 70,000 pounds he derived from selling off his patrimony … for which some part of this amount de Vere acquired a splendid reputation for nurture of the arts and sciences”.[192]

Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship[edit]

Main articles: Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship and Prince Tudor theory

The Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare authorship proposes that the Earl of Oxford wrote the plays and poems traditionally attributed to William Shakespeare of Stratford-upon-Avon. Though rejected by nearly all academic Shakespeareans,[193] it has been among the most popular alternative Shakespeare authorship theories since the 1920s.[194] The Oxfordian theory was the central theme of the 2011 film Anonymous, directed by Roland Emerich and starring Rhys Ifans and Jamie Campbell Bower as Edward de Vere, and Vanessa Redgrave and Joely Richardson as Queen Elizabeth I. The film has received some criticism for not being historically accurate in its entirety, with some aspects of the plot relating to dates of real events and their location, characters’ relationships to one another and deaths being dramatized or displayed out of chronological order.[195]

Comparing the Work of Edward de Vere and William Shakespeare

Get the facts on the Shakespeare authorship debate

By

Updated on January 28, 2019

Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford, was a contemporary of Shakespeare and a patron of the arts. A poet and dramatist in his own right, Edward de Vere has since become the strongest candidate in the Shakespeare authorship debate.

Edward de Vere: A Biography

De Vere was born in 1550 (14 years before Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon) and inherited the title of 17th Earl of Oxford before his teenage years. Despite receiving a privileged education at Queen’s College and Saint John’s College, De Vere found himself in financial dire straights by the early 1580s – which led to Queen Elizabeth granting him an annuity of £1,000.

It is suggested that De Vere spent the later part of his life producing literary works but disguised his authorship to uphold his reputation in court. Many believe that these manuscripts have since become credited to William Shakespeare.

De Vere died in 1604 in Middlesex, 12 years before Shakespeare’s death in Stratford-upon-Avon.

Edward de Vere: The Real Shakespeare?

https://www.thoughtco.com/who-was-edward-de-vere-2984933

Could De Vere really be the author of Shakespeare’s plays? The theory was first proposed by J. Thomas Looney in 1920. Since then the theory has gained momentum and has received support from some high-profile figures including Orson Wells and Sigmund Freud.

Although all the evidence is circumstantial, it is none-the-less compelling. The key points in the case for De Vere are as follows:

- “Thy countenance shakes spears” is how De Vere was once described in royal court. Could this have been a codified reference to De Vere’s literary activities? In print, Shakespeare’s name appeared as “Shake-speare.”

- Many of the plays parallel events from De Vere’s life. In particular, supporters consider Hamlet to be a deeply biographical character.

- De Vere had the right education and social standing to write in detail about the classics, law, foreign countries, and language. William Shakespeare, a country bumpkin from Stratford-upon-Avon, would simply have been unequipped to write about such things.

- Some of De Vere’s early poetry appeared in print under his own name. However, this stopped soon after texts were printed under Shakespeare’s name. So, it’s been suggested that De Vere took on his pseudonym when Shakespeare’s earliest works were first published: The Rape of Lucrece (1593) and Venus and Adonis (1594). Both poems were dedicated to Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, who was considering marrying De Vere’s daughter.

- De Vere was well traveled and spent most of 1575 in Italy. 14 of Shakespeare’s plays have Italian settings.

- Shakespeare was heavily influenced by Arthur Golding’s translation of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. There is some evidence to suggest Golding lived in the same household as De Vere at this time.

Despite this compelling circumstantial evidence, there is no concrete proof that Edward de Vere was the real author of Shakespeare’s plays. Indeed, it is conventionally accepted that 14 of Shakespeare’s plays were written after 1604 – the year of De Vere’s death.

The debate goes on.

Top 18 Reasons Why Edward de Vere (Oxford) Was Shakespeare

History has left us many clues indicating that Edward de Vere, 17th Earl of Oxford (1550–1604), wrote plays and poetry under the pen name “William Shakespeare.” Many people believe these clues, taken together, add up to a very strong case for Oxford as the true author of Hamlet, King Lear, the Sonnets, and other works traditionally attributed to the man from Stratford. Following are some of the main reasons for thinking Oxford was Shakespeare.

#1. Hidden Writer

Edward de Vere (Oxford) was known during his lifetime as a secret writer who did not allow his works to be published under his name. In 1589, the anonymous author of The Arte of English Poesie stated: “I know very many notable gentlemen in the court that have written commendably and suppressed it … or else suffered it to be published without their own names to it, as if it were a discredit for a gentleman to seem learned and to show himself amorous of any good art.” This 1589 book also referred to “courtly makers, noblemen … who have written excellently well, as it would appear if their doings could be found out and made public with the rest. Of which number is first that noble gentleman Edward Earl of Oxford …” (emphases added). Francis Meres said in 1598 that Oxford was one of the best writers of comedy. Yet no comedies have come down to us under his name.

#2. “Shakespeare” as a Pseudonym

In a 1578 Latin oration, Gabriel Harvey said of Oxford, “vultus tela vibrat,” which may be translated as “thy countenance shakes spears.” This may have been an inspiration for the later use of “Shakespeare” as a pen name. Pseudonyms were so common in the Elizabethan Era (the “Golden Age” of pseudonyms), that almost every writer used one at one time or another. Archer Taylor and Frederic J. Mosher, in their seminal book on pseudonymous writings, The Bibliographical History of Anonyma and Pseudonyma (University of Chicago Press, 1951), stated: “In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the Golden Age of pseudonyms, almost every writer used a pseudonym at some time or other during his career.”

Pseudonyms were important because a person could be punished for saying things that displeased the authorities. For example, a man with the sadly fitting name of John Stubbs had his hand cut off because he wrote that Queen Elizabeth I was too old to marry. People in the nobility had an additional reason for hiding their identities if they wrote poetry (which was considered frivolous) or plays for the public stage (which were considered beneath a nobleman’s dignity). See quotations above from The Arte of English Poesie (1589).

“Shakespeare,” as a pen name, could be a reference to Athena, the Greek goddess of wisdom who came to be viewed during the Renaissance as a patron of the arts and learning. She is often depicted shaking a spear. Pseudonyms were used because writings that offended the authorities could subject an author to punishment. Also, where the nobility were concerned, it was considered beneath their dignity to publish poetry, which was deemed frivolous, or plays for the public theatres, which were scandalous places where thievery, prostitution, and gambling occurred.

#3. Patron of the Arts

Oxford himself was a patron of the arts who loved theatre and poetry and commissioned various books and translations. Twenty-eight books were dedicated to him during his life. Oxford sponsored two theatre troupes: a men’s troupe and a boys’ troupe. He leased the Blackfriars Theatre in the 1580s for his boys’ troupe.

#4. Titian’s Adonis with Hat

The long narrative poem, Venus and Adonis, the first work published under the name William Shakespeare, describes Adonis wearing a “bonnet.” This mirrors one of the many paintings of Venus and Adonis by the Venetian artist, Titian – the only one that shows Adonis wearing a bonnet. This could only have been seen at Titian’s studio in Venice, a city where Oxford spent a great deal of time during his mid-twenties.

#5. Ovid’s Metamorphoses

Ovid’s Metamorphoses, which is recognized as one of Shakespeare’s most influential sources, second only to the Bible, was translated into English by Arthur Golding, Oxford’s uncle. Oxford and Golding were living in the same household when the translation was being completed.

#6. “To Be or Not to Be”

The famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy in Hamlet echoes Gerolamo Cardano’s Comforte (De Consolatione), written in 1542: “What should we account of death to be resembled to anything better than a sleep. . . . We are assured not only to sleep, but also to die.” Oxford commissioned an English translation of Cardano’s Comforte by Thomas Bedingfield (1573) for which Oxford wrote the preface.

#7. “Polonius,” AKA Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley

Polonius in Hamlet has long been recognized as a parody of Sir William Cecil, Lord Burghley. Oxford had a long and often uneasy relationship with Burghley, who was first, his guardian, then later his father-in-law. Polonius’ advice to his son Laertes in Hamlet echoes a list of maxims that Burghley posted for the benefit of his household. The list was never made public until after Hamlet was published. In Hamlet, Polonius sends a servant to spy on his son when he is away at university, just as Burghley did with his son. Burghley sponsored Parliamentary legislation that made Wednesdays “fish-days,” a fact that may have inspired Shakespeare to have Hamlet call Polonius a “fishmonger.” Burghley’s motto was “Cor unum, via una” (“One heart, one way”). In the First Quarto of Hamlet, the Polonius character is named “Corambis,” (“double-hearted”), a parody of Burghley’s motto. Hamlet was not published until after Burghley died, as Oxford had no need to provoke his father-in-law while he lived.

#8. Young Men Falling Out at Tennis

Polonius’ mention of young men “falling out at tennis” in Hamlet refers to a famous incident in which Oxford had a quarrel on a tennis court with Sir Philip Sidney in 1579. Oxford and Sidney were rivals in many ways. Both had sought the hand of Burghley’s daughter Anne; they also disagreed on politics and literature. Sidney was playing tennis with some friends when Oxford came along and asked if he could join in. Sidney simply ignored him. In the ensuing quarrel, Oxford called Sidney a “puppy.” Oxford would later parody Sidney as Sir Andrew Aguecheek in Twelfth Night, Slender in Merry Wives, and the Dauphin in Henry V, who says that his horse is his mistress (Sidney wrote a sonnet to his horse).

#9. Captured by Pirates!

One of the plot twists in Hamlet finds Hamlet being captured by pirates on his way to England and being left naked on the shore of Denmark. Oxford was returning to England from the continent when he was captured by pirates who left him naked on the shore of England.

#10. The “Fair Youth”

Henry Wriothesley, the Third Earl of Southampton, was a beautiful young nobleman to whom Shakespeare expressly dedicated the two narrative poems Venus and Adonis and Rape of Lucrece. Many scholars believe that Southampton was also the “Fair Youth” of Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Around the time that the Sonnets are thought to have been written, Lord Burghley was trying to persuade a reluctant Southampton to marry Oxford’s daughter Elizabeth, who was also, of course, Burghley’s granddaughter. In the first 17 sonnets, the poet encourages the Fair Youth to marry and procreate. It would have been entirely presumptuous for William Shakspere, a commoner, to write sonnets offering marital advice to a young nobleman. The Sonnets make much more sense if they are seen as coming from an older nobleman to a younger one whom the older nobleman hopes will become his son-in-law.

#11. Oxford’s Geneva Bible

Oxford’s handwritten notations in his personal copy of the Geneva Bible show a strong correlation to biblical references in Shakespeare’s works, as Professor Roger Stritmatter demonstrated in his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Massachusetts. The more often a biblical passage is referenced in Shakespeare’s works, the more likely it is to have been marked in Oxford’s Bible.

#12. Dividing the Kingdom

Oxford had three daughters, just as King Lear did. And just as Lear divided his kingdom among his daughters while he still lived, Oxford placed his family lands in trust for the benefit of his daughters while he lived.

#13. 3,000 Ducats

In The Merchant of Venice, Antonio, the merchant, borrows 3,000 ducats from Shylock, the moneylender, to help finance Bassanio’s wooing of Portia. In real life, Oxford borrowed 3,000 pounds from a moneylender named Michael Lok, to finance a voyage seeking a northwest passage to India. The character Shylock greatly resembles Gaspar Ribeiro, a Venetian Jew who was successfully sued for making a usurious 3,000-ducat loan. Ribeiro lived in the same parish in Venice where Oxford attended church.

#14. Baptista and Spinola

Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew features a rich man named Baptista Minola, who is the father of two daughters eligible for marriage, Kate and Bianca. In Italy, Oxford borrowed money from a man named Baptista Nigrone and also from a man named Pasquale Spinola, whose names must have inspired Minola’s name.

#15. That Rare Italian Master, Julio Romano

In The Winter’s Tale, a statue of the queen is described as “a piece many years in doing and now newly performed by that rare Italian master, Julio Romano . . . .” Romano is the only artist mentioned by name in Shakespeare’s works. Many critics have scoffed at Shakespeare’s ignorance in thinking that Romano was a sculptor when he was actually a painter. But Shakespeare was right and the critics were wrong. Romano was a sculptor as well as a painter, as witnessed by his sculpture on the tomb of Baldassare Castiglione in Mantua. Castiglione, by the way, was one of Oxford’s heroes and Oxford commissioned the translation of Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier into Latin so that noblemen all over Europe could benefit from it. Mantua is along the route Oxford is known to have traveled, and he would likely have wanted to pay his respects there to one of his spiritual mentors.

#16. Romano’s Room

Speaking of Julio Romano, also in Mantua are Romano’s paintings of the Trojan War on the walls and ceiling of the Sala di Troia (“Room of Troy”) in the Palazzo Ducale (ducal palace). In Shakespeare’s narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece, the heroine, after she has been raped, goes into a room with paintings on the walls depicting the Trojan War. The descriptions of those paintings, which encompass over 200 lines, bear striking resemblances to the paintings in the Sala di Troia.

#17. Hamlet and Beowulf

Shakespeare’s Hamlet gets much of its plot from versions of an old tale as told by the Dane Saxo Grammaticus and the Frenchman François de Belleforest. Neither of these stories, however, contains anything like the scene where Shakespeare’s dying Hamlet turns to his friend Horatio and implores him:

Horatio, I am dead;

Thou livest; report me and my cause aright

To the unsatisfied.

. . .

O good Horatio, what a wounded name,

Things standing thus unknown, shall live behind me!

If thou didst ever hold me in thy heart

Absent thee from felicity awhile,

And in this harsh world draw thy breath in pain,

To tell my story.

This part of the story may have been inspired by the ending of the Old English epic poem Beowulf, the first known work of literature in the English language. When the hero Beowulf is dying from wounds inflicted on him during a battle with a dragon, he turns to his fellow warrior, Wiglaf, and asks him to create a burial mound in his memory:

The battle-famed bid ye to build them a grave-hill . . .

As a memory-mark to the men I have governed,

Aloft it shall tower . . .

That earls of the ocean hereafter may call it

Beowulf’s barrow.

Thus, both Hamlet and Beowulf use their dying breaths to ask that they be remembered. In Oxford’s time, however, Beowulf could not be bought from a bookseller, nor borrowed from a library. In fact, there was only one copy of it in existence, in manuscript form. That copy was owned by a man named Laurence Nowell. And who was Laurence Nowell? One of Oxford’s tutors.

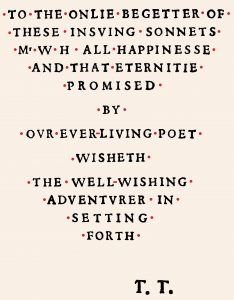

#18. “Our Ever-Living Poet”

Shakespeare’s Sonnets were first published in 1609. There are indications on the dedication page that the author was no longer living at that time. First, the dedication is signed by the publisher, Thomas Thorpe, not by the author, suggesting that the author was not alive to write the dedication. More significantly, the dedication refers to the author as “ever-living.” This is a phrase that was used metaphorically to refer to a person who was no longer alive, but who would live on through his works in our minds and hearts. The Earl of Oxford was no longer living in 1609, while the man from Stratford, who is usually credited with writing the works of Shakespeare, would live on for another seven years. Stratfordian scholars have never been able to explain why the phrase “ever-living” would have been applied to a living person.

Further Reading

The above are just a few of the many connections between Oxford’s life and the works of Shakespeare. You can learn more at the following links:

See the SOF “Shakespeare Authorship 101” page for a concise overview of reasons to doubt that William Shakspere of Stratford-upon-Avon wrote any of the plays or poems in the first place.

See also the in-depth review of “The Case for Oxford” by historian Ramon Jiménez.

Poetic Justice for the True Shakespeare? (introducing major new studies of parallels between Oxford’s early poetry and private letters and numerous works in the Shakespeare canon)

Ten Clues to the Identity of Edward de Vere as “William Shakespeare” (about 1,300 words)

Why Would Anyone Need to Fake Shakespeare’s Authorship? (about 3,000 words)

Hamlet as Autobiography: An Oxfordian Analysis by Felicia Londré (about 4,800 words)

The Case for Oxford Revisited by Ramon Jiménez (about 8,500 words)

“Shakespeare” Identified in Edward De Vere, the Seventeenth Earl of Oxford by J. Thomas Looney (original public domain text as published in London in 1920) (click here for the reasonably priced modern scholarly edition of this classic masterpiece of literary detective work)

About the Author

Tom Regnier (1950–2020) earned his J.D. summa cum laude in 2003 at the University of Miami School of Law, where he taught “Shakespeare and the Law” for many years as an adjunct professor. He earned his LL.M. in 2009 at Columbia Law School, where he was a Harlan F. Stone Scholar. He also taught at Chicago’s John Marshall Law School. He became a prolific independent Shakespearean scholar, combining his interests in Shakespeare and the law. He served as President of the SOF (2014–18) and was honored as Oxfordian of the Year in 2016. You can read here about his final public lecture, on the centennial of the Oxfordian theory, with links to his obituary, his major writings and speeches, and much additional information.

[published Aug. 18, 2019, updated 2021]

Notes[edit]

- ^ May 1980, pp. 5–8; Nelson 2003, pp. 191–194.

- ^ May 2007, p. 61.

- ^ May 1991, pp. 53–54; May 2007, p. 62.

- ^ Gurr 1996, p. 306.

- ^ Jump up to:a b May 1980, p. 9.

- ^ Chambers 1923, pp. 100–102; Nelson 2003, pp. 391–392.

- ^ Records of Early English Drama (REED), accessed 22 March 2013; Nelson 2003, pp. 247–248, 391

- ^ Thomas Birch, Memoirs of the reign of Queen Elizabeth, vol. 1 (London, 1754), p. 37.

- ^ “Bank of England Inflation Calculator”. Archived from the original on 6 July 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Nelson 2003, p. 215

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nelson 2003, p. 156

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 23

- ^ Pearson 2005, p. 14; Nelson 2003, pp. 34.

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 25.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Nelson 2003, p. 157

- ^ Pearson 2005, p. 14

- ^ Pearson 2005, p. 36

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 20–21

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 39; Ward 1928, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 23–4: ‘It is not unknown to others, and I have had experience thereof myself, how earnest a desire your Honour hath naturally grafted in you to read, peruse and communicate with others, as well as the histories of ancient times and things done long ago, as also the present estate of things in our days, and that not without a certain pregnancy of wit and ripeness of understanding’.

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 40–41

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 41

- ^ Jump up to:a b Nelson 2003, p. 407

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 49

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 42–3, 45

- ^ Ward 1928, p. 27

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 48: “I did my best to have the jury find the death of a poor man whom he killed in my house to be found se defendendo”.

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 31–33

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 30–31

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 49–50

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 50

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 52.

- ^ Ward 1928, pp. 39–41, 48.

- ^ May 1980, p. 6.

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 71

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 69–70: George Delves, one of the defenders in the tournament, wrote to the Earl of Rutland that ‘There is no man of life and agility in every respect in the Court but the Earl of Oxford’

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 73

- ^ May 2007, pp. 61–62

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 71–2

- ^ Colethorpe, Marion E. “The Elizabethan Court Day by Day – 1571” (PDF). folgerpedia.folger.edu. Folger Shakespeare Library. Retrieved 25 October 2020.

- ^ Pearson 2005, pp. 28–29

- ^ Pearson 2005, pp. 28, 38

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 101, 106–107, 141

- ^ PRO 1966, p. 450

- ^ Green 2009, pp. 58, 76

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 53–54, 80–82, 84

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 99, 103

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 108–16

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 119

- ^ Pearson 2005, pp. 43–44;Nelson 2003, p. 120

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 142

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 125–30, 176

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 127, 129

- ^ Stow & Howes 1631, p. 868; Nelson 2003, p. 229.

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 129

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 132

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 131

- ^ May 1980, p. 6

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 135–137

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 141–54

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 154

- ^ May 1980, p. 6

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 176–7

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 172–173, 176, 179

- ^ Bryant 2017, p. 156

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 187

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 173

- ^ Pearson 2005, p. 229

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 186–8

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 180

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 181

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 190

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 195–200

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 230

- ^ Nelson 2003, pp. 200–201, 203

- ^ Nelson 2003, p. 228