The Secret Life of Melusine: Mysterious Mermaid & Serpent Mother of European Nobility

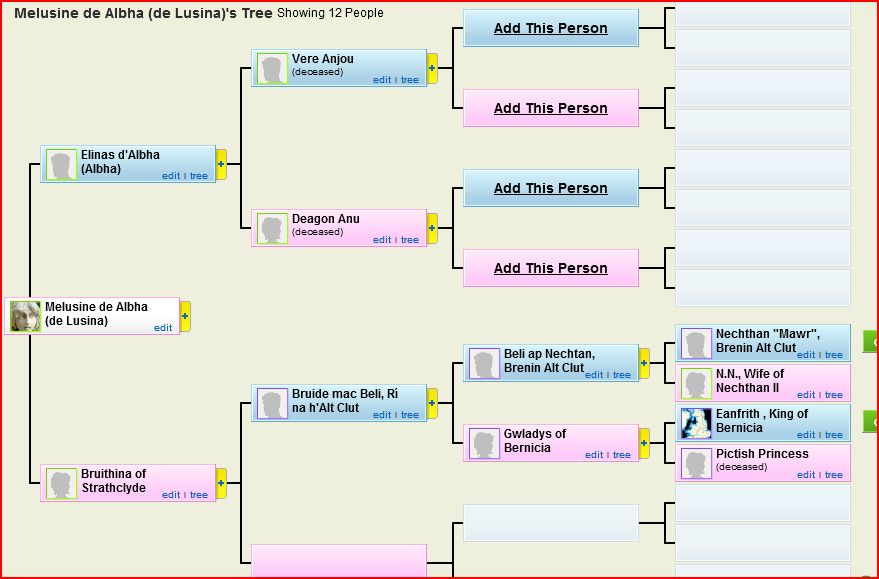

I found Melusine in my family tree. I’m not exactly sure how we’re related. But here’s what I found:

Melusine (Lusina), Princess Maelasanu, Melusine de Lusina (Milouziena des Scythe) Vere the First, Scythian Princess of the Picts of Albha, the Dragon Princess and Fairy Daughter of Satan, Witch, Druidhe, Druid Fey de la Fontaine de Soif de Lusignan

740–

BIRTH ABT 740

DEATH Unknown mother-in-law of 33rd great-grandaunt

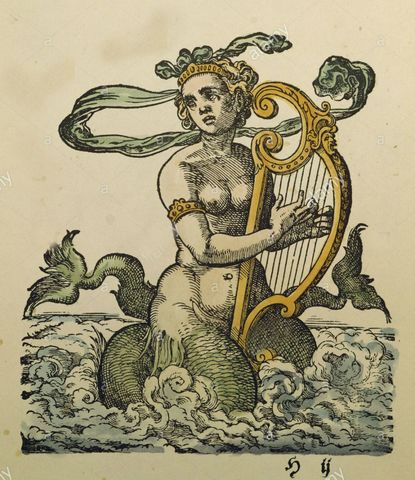

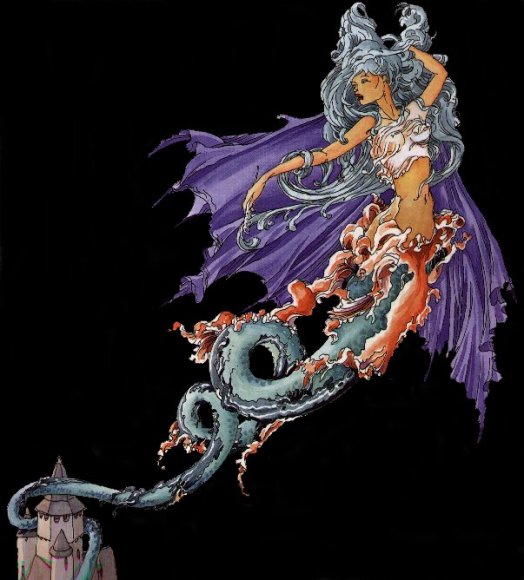

Melusine is the spirit of freshwater, usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down, much like the mythical mermaid. She is also frequently illustrated with two tails. The image of Melusine is so famous and enduring that, perhaps without knowing her by name, we still recognize her image today as the logo for Starbucks Coffee.

The Starbucks Logo: Melusine and her two tails; Deriv (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Sixteenth-century Theologian Martin Luther referred to Melusine unfavorably several times as a succubus, and nineteenth-century composer Felix Mendelssohn wrote a concert overture titled “The Fair Melusina”.

Melusine or Melusina is a figure of European folklore and mythology, a female spirit of fresh water in a sacred spring or river, usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down, much like a two-tailed mermaid. She is sometimes referred to as the Serpent Mother of European Royalty.

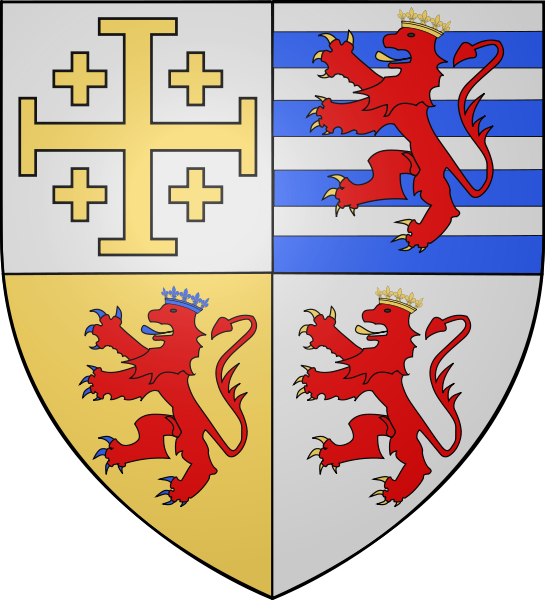

https://atlanteangardens.blogspot.com… According to the book, “The Serpent And The Swan: The Animal Bride In Folklore And Literature,” the name “Melusine” was used as an abbreviation of the words ‘Mere des Lusignan’ or ‘Mother of the Lusignans.’ The House of Lusignan was a royal house of French origin, which at various times ruled several principalities in Europe and the Levant, including the kingdoms of Jerusalem, Cyprus, and Armenia, from the 12th through the 15th centuries during the Middle Ages. Presentation by Dr. Sharonah Fredrick Visuals by Kendra Bruning

These days, images of Melusine are still seen in the Vendée region of Poitou, western France, where one can drink Melusine-brand beer and eat Melusine-style baguettes. In Vouvant, paintings of her and her sons decorate the “Tour Melusine,” the ruins of a Lusignan castle guarding the banks of the River Mère, where visitors of the tower can lunch at the Cafe Melusine nearby.

Tour Mélusine ( Public Domain )

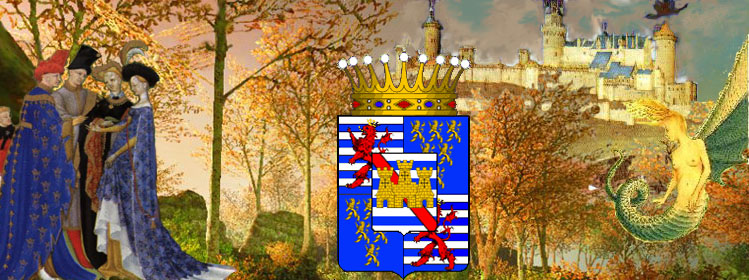

The legends of Melusine are especially connected with the northern and western areas of France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries. Her name derives from Mère Lusine (“Mother of the Lusignans”), connecting her with Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be her descendants. The legend of Melusine, therefore, is related to the territorial and dynastic expansion of her descendants beyond Lusignan across the Mediterranean to distant Armenia during the crusades (1095 – 1291).

The Fairy and the King: The Legend of Pressyne, the Mother of Melusine

One day, at the time of the Crusades, Elynas, the King of Albany, went hunting and saw a beautiful lady in the forest. The lady’s name was Pressyne. Elynas persuaded her to marry him and she agreed. However, Pressyne demanded a promise from him that he must never enter her chamber when she birthed or bathed her children.

The couple lived happily for some time until Pressyne gave birth to triplets. When, as one would expect to happen in these stories, her husband broke his promise, Pressyne left the kingdom, together with her three daughters, and traveled to the lost Isle of Avalon where her daughters — Melusine, Melior and Palatyne — would grow up.

The woman took her children to the lost Isle of Avalon ( CC BY 2.0 )

On their fifteenth birthday, the eldest daughter, Melusine, asked her mother why she separated them from their father and took them to Avalon. After hearing of their father’s broken promise, Melusine sought revenge. She rallied her sisters and the three sisters captured Elynas and trapped him in a mountain. When she heard what her daughters have done, Pressyne punished them for their disrespect to their father. She condemned Melusine to take the form of a fish from the waist down every Saturday. In other versions of the legend, Melusine was condemned to take on the form of a serpent on Saturdays.

Middle Ages

People Involved

Melusine, Count of Anjou (Melusine’s husband)

Outcome

Count of Anjou loses Melusine forever

Melusine is a figure of European folklore, a female spirit of fresh water in a sacred spring or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down (much like a mermaid). She is also sometimes illustrated with wings, two tails, or both. Her legends are especially connected with the northern and western areas of France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries. She is also connected with Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled the island from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be descended from Melusine.

Versions in Literature

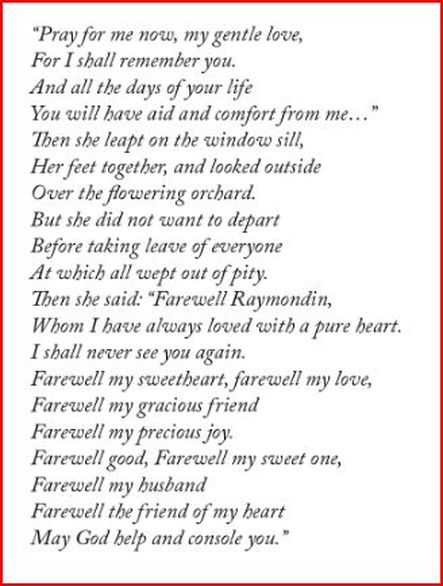

The most famous literary version of Melusine tales, that of Jean d’Arras, compiled about 1382–1394, was worked into a collection of “spinning yarns” as told by ladies at their spinning. Coudrette (Couldrette) wrote The Romans of Partenay or of Lusignen: Otherwise known as the Tale of Melusine, giving source and historical notes, dates and background of the story. He goes into detail and depth about the relationship of Melusine and Raymondin, their initial meeting and the complete story.

The tale was translated into German in 1456 by Thüring von Ringoltingen, the version of which became popular as a chapbook. It was later translated into English c. 1500, and often printed in both the 15th century and the 16th century. A prose version is entitled the Chronique de la princesse (Chronicle of the Princess).

It tells how in the time of the Crusades, Elynas, the King of Albany (an old name for Scotland or Alba), went hunting one day and came across a beautiful lady in the forest. She was Pressyne, mother of Melusine. He persuaded her to marry him but she agreed, only on the promise — for there is often a hard and fatal condition attached to any pairing of fay and mortal — that he must not enter her chamber when she birthed or bathed her children. She gave birth to triplets. When he violated this taboo, Pressyne left the kingdom, together with her three daughters, and traveled to the lost Isle of Avalon.

The three girls — Melusine, Melior, and Palatyne — grew up in Avalon. On their fifteenth birthday, Melusine, the eldest, asked why they had been taken to Avalon. Upon hearing of their father’s broken promise, Melusine sought revenge. She and her sisters captured Elynas and locked him, with his riches, in a mountain. Pressyne became enraged when she learned what the girls had done, and punished them for their disrespect to their father. Melusine was condemned to take the form of a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. In other stories, she takes on the form of a mermaid.

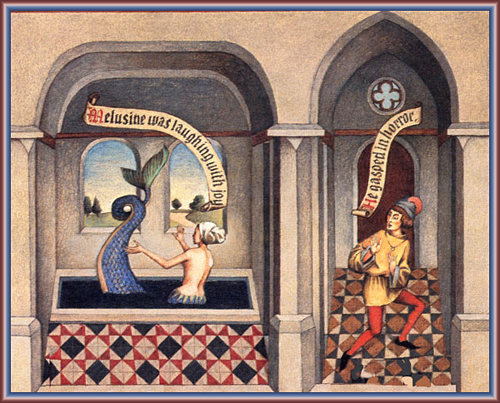

Raymond of Poitou came across Melusine in a forest of Coulombiers in Poitou in France, and proposed marriage. Just as her mother had done, she laid a condition: that he must never enter her chamber on a Saturday. He broke the promise and saw her in the form of a part-woman, part-serpent, but she forgave him. When, during a disagreement, he called her a “serpent” in front of his court, she assumed the form of a dragon, provided him with two magic rings, and flew off, never to return.

In The Wandering Unicorn by Manuel Mujica Láinez, Melusine tells her tale of several centuries of existence, from her original curse to the time of the Crusades.

Legends

Melusine legends are especially connected with the northern areas of France, Poitou and the Low Countries, as well as Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled the island from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be descended from Melusine. Oblique reference to this was made by Sir Walter Scott who told a Melusine tale in The Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–1803) stating that

| “the reader will find the fairy of Normandy, or Bretagne, adorned with all the splendour of Eastern description. The fairy Melusina, also, who married Guy de Lusignan, Count of Poitou, under condition that he should never attempt to intrude upon her privacy, was of this latter class. She bore the count many children, and erected for him a magnificent castle by her magical art. Their harmony was uninterrupted until the prying husband broke the conditions of their union, by concealing himself to behold his wife make use of her enchanted bath. Hardly had Melusina discovered the indiscreet intruder, than, transforming herself into a dragon, she departed with a loud yell of lamentation, and was never again visible to mortal eyes; although, even in the days of Brantome, she was supposed to be the protectress of her descendants, and was heard wailing as she sailed upon the blast round the turrets of the castle of Lusignan the night before it was demolished.” | ” |

The Luxembourg family also claimed descent from Melusine through their ancestor Siegfried. When in 963 A.D. Count Siegfried of the Ardennes (Sigefroi in French; Sigfrid in Luxembourgish) bought the feudal rights to the territory on which he founded his capital city of Luxembourg, his name became connected with the local version of Melusine. This Melusina had essentially the same magic gifts as the ancestress of the Lusignans, magically making the Castle of Luxembourg on the Bock rock (the historical center point of Luxembourg City) appear the morning after their wedding.

On her terms of marriage, she too required one day of absolute privacy each week. Alas, Sigfrid, as the Luxem-bourgish call him, “could not resist temptation, and on one of the forbidden days he spied on her in her bath and discovered her to be a mermaid. When he let out a surprised cry, Melusina caught sight of him, and her bath immediately sank into the solid rock, carrying her with it. Melusina surfaces briefly every seven years as a beautiful woman or as a serpent, holding a small golden key in her mouth. Whoever takes the key from her will set her free and may claim her as his bride.” In 1997 Luxembourg issued a postage stamp commemorating her.

Martin Luther knew and believed in the story of another version of Melusine, die Melusina zu Lucelberg (Lucelberg in Silesia), whom he referred to several times as a succubus (Works, Erlangen edition, volume 60, pp 37–42). Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote the tale of Die Neue Melusine in 1807 and published it as part of Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre. The playwright Franz Grillparzer brought Goethe’s tale to the stage and Felix Mendelssohn provided a concert overture “The Fair Melusina,” his Opus 32.

Melusine is one of the pre-Christian water-faeries who were sometimes responsible for changelings. The “Lady of the Lake”, who spirited away the infant Lancelot and raised the child, was such a water nymph. Other European water sprites include Loreleiand the nixie.

“Melusina” would seem to be an uneasy name for a girl-child in these areas of Europe, but Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal and Munster, mistress of George I of Great Britain, was christened Melusine in 1667.

The chronicler Gerald of Wales reported that Richard I of England was fond of telling a tale according to which he was a descendant of a countess of Anjou who was in fact the fairy Melusine, concluding that his whole family “came from the devil and would return to the devil”. The Angevin legend told of an early Count of Anjou who met a beautiful woman when in a far land, where he married her. He had not troubled to find out about her origins. However, after bearing him four sons, the behaviour of his wife began to trouble the count. She attended church infrequently, and always left before the the Mass proper.

One day he had four of his men forcibly restrain his wife as she rose to leave the church. Melusine, evaded the men and clasped the two youngest of her sons and in full view of the congregation carried them up into the air and out of the church through its highest window. Melusine and her two sons were never seen again. One of the remaining sons was the ancestor, it was claimed, of the later Counts of Anjou and the Kings of England.

Related Legends

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville recounts a legend about Hippocrates’ daughter. She was transformed into a hundred-foot long dragon by the goddess Diane, and is the “lady of the manor” of an old castle. She emerges three times a year, and will be turned back into a woman if a knight kisses her, making the knight into her consort and ruler of the islands. Various knights try, but flee when they see the hideous dragon; they die soon thereafter. This appears to be an early version of the legend of Melusine.

The Mermaid and the Gentleman: The Legend of Melusine, the Mother of Kings

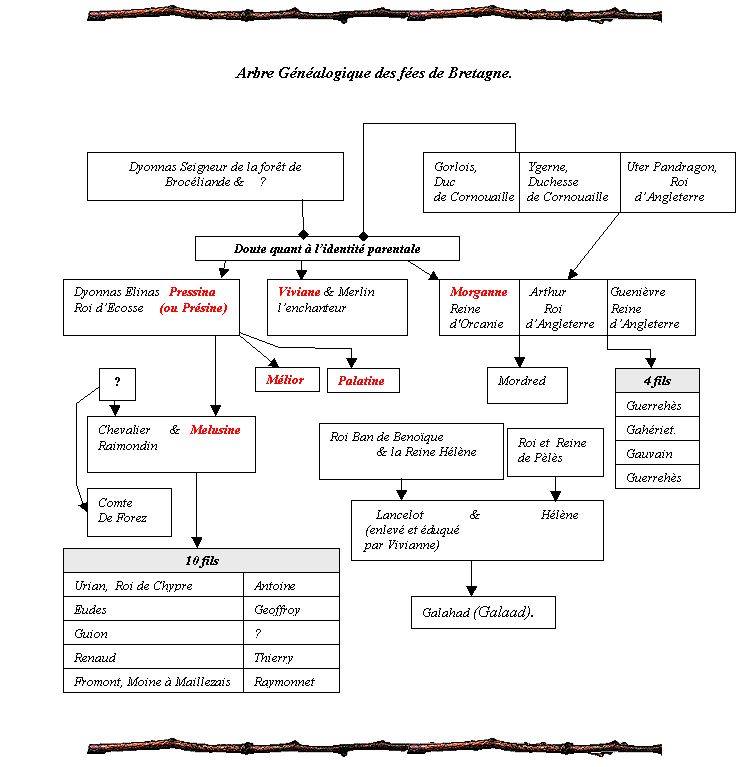

Sometime later, history repeated itself when, while out hunting in the forests of the Ardennes, Raymondin, Lord of Forez in Poitou, a poor but noble gentleman, met the beautiful Melusine who was sitting beside a fountain in a glimmering white dress…

Melusine

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

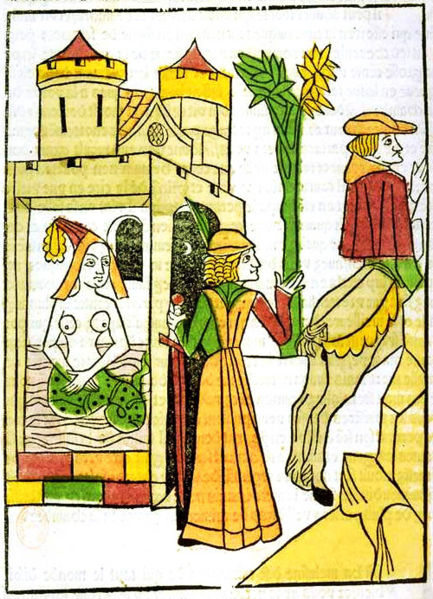

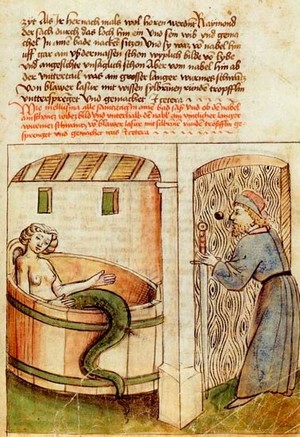

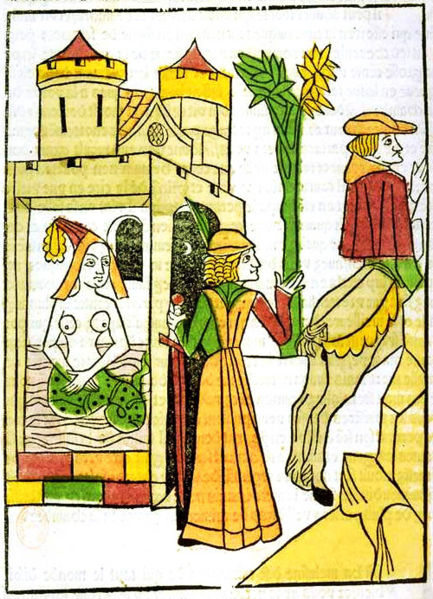

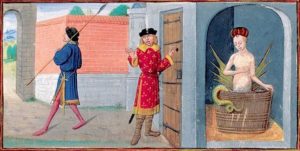

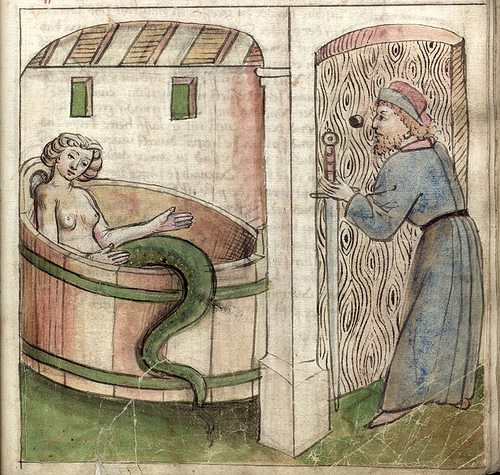

Melusine-WikipediaFor other uses, see Melusine (disambiguation).Melusine’s secret discovered, from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, ca 1450–1500. Bibliothèque nationale de France.

Melusine (French: [melyzin]) or Melusina is a figure of European folklore and mythology, a female spirit of fresh water in a sacred spring or river. She is usually depicted as a woman who is a serpent or fish from the waist down (much like a mermaid). She is also sometimes illustrated with wings, two tails, or both. Her legends are especially connected with the northern and western areas of France, Luxembourg, and the Low Countries.

The House of Luxembourg (which ruled the Holy Roman Empire from AD 1308 to AD 1437 as well as Bohemia and Hungary), the House of Anjou and their descendants the House of Plantagenet (kings of England) and the French House of Lusignan (kings of Cyprus from AD 1205–1472, and for shorter periods over Armenia and Jerusalem) are said in folk tales and medieval literature to be descended from Melusine.

One tale says Melusine herself was the daughter of the fairy Pressyne and king Elinas of Albany (now known as Scotland). Melusine’s mother leaves her husband, taking her daughters to the isle of Avalon after he breaks an oath never to look in at her and her daughter in their bath. The same pattern appears in stories where Melusine marries a nobleman only after he makes an oath to give her privacy in her bath; each time, she leaves the nobleman after he breaks that oath. Shapeshifting and flight on wings away from oath-breaking husbands also figure in stories about Melusine. According to Sabine Baring-Gould in Curious Tales of the Middle Ages, the pattern of the tale is similar to the Knight of the Swan legend which inspired the character “Lohengrin” in Wolfram von Eschenbach‘s Parzival. [1]

Contents

- 1Literary versions

- 2Legends

- 3Related legends

- 4Structural interpretation

- 5References in the arts

- 6See also

- 7References

- 8External links

Literary versions

Raymond walks in on his wife, Melusine, in her bath and discovers she has the lower body of a serpent. Illustration from the Jean d’Arras work, Le livre de Mélusine (The Book of Melusine), 1478.

The most famous literary version of Melusine tales, that of Jean d’Arras, compiled about 1382–1394, was worked into a collection of “spinning yarns” as told by ladies at their spinning coudrette (coulrette (in French)). He wrote The Romans of Partenay or of Lusignen: Otherwise known as the Tale of Melusine, giving source and historical notes, dates and background of the story. He goes into detail and depth about the relationship of Melusine and Raymondin, their initial meeting and the complete story.

The tale was translated into German in 1456 by Thüring von Ringoltingen, which version became popular as a chapbook. It was later translated into English, twice, around 1500, and often printed in both the 15th century and the 16th century. There is also a Castilian and a Dutch translation, both of which were printed at the end of the 15th century. [2] A prose version is entitled the Chronique de la princesse (Chronicle of the Princess).

It tells how in the time of the Crusades, Elynas, the King of Albany (an old name for Scotland or Alba), went hunting one day and came across a beautiful lady in the forest. She was Pressyne, mother of Melusine. He persuaded her to marry him but she agreed, only on the promise—for there is often a hard and fatal condition attached to any pairing of fay and mortal—that he must not enter her chamber when she birthed or bathed her children. She gave birth to triplets. When he violated this taboo, Pressyne left the kingdom, together with her three daughters, and traveled to the lost Isle of Avalon.

The three girls—Melusine, Melior, and Palatyne—grew up in Avalon. On their fifteenth birthday, Melusine, the eldest, asked why they had been taken to Avalon. Upon hearing of their father’s broken promise, Melusine sought revenge. She and her sisters captured Elynas and locked him, with his riches, in a mountain. Pressyne became enraged when she learned what the girls had done, and punished them for their disrespect to their father. Melusine was condemned to take the form of a serpent from the waist down every Saturday. In other stories, she takes on the form of a mermaid.

Raymond of Poitou came across Melusine in a forest of Coulombiers in Poitou in France, and proposed marriage. Just as her mother had done, she laid a condition: that he must never enter her chamber on a Saturday. He broke the promise and saw her in the form of a part-woman, part-serpent, but she forgave him. When, during a disagreement, he called her a “serpent” in front of his court, she assumed the form of a dragon, provided him with two magic rings, and flew off, never to return.[3]

In The Wandering Unicorn by Manuel Mujica Láinez, Melusine tells her tale of several centuries of existence, from her original curse to the time of the Crusades. [4]

Legends

Melusine legends are especially connected with the northern areas of France, Poitou and the Low Countries, as well as Cyprus, where the French Lusignan royal house that ruled the island from 1192 to 1489 claimed to be descended from Melusine. Oblique reference to this was made by Sir Walter Scott who told a Melusine tale in Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802–1803) stating that

the reader will find the fairy of Normandy, or Bretagne, adorned with all the splendour of Eastern description. The fairy Melusina, also, who married Guy de Lusignan, Count of Poitou, under condition that he should never attempt to intrude upon her privacy, was of this latter class. She bore the count many children, and erected for him a magnificent castle by her magical art. Their harmony was uninterrupted until the prying husband broke the conditions of their union, by concealing himself to behold his wife make use of her enchanted bath. Hardly had Melusina discovered the indiscreet intruder, than, transforming herself into a dragon, she departed with a loud yell of lamentation, and was never again visible to mortal eyes; although, even in the days of Brantome, she was supposed to be the protectress of her descendants, and was heard wailing as she sailed upon the blast round the turrets of the castle of Lusignan the night before it was demolished.

Melusine by Ludwig Michael von Schwanthaler (1845)

The Luxembourg family also claimed descent from Melusine through their ancestor Siegfried.[5] When in 963 A.D. Count Siegfried of the Ardennes (Sigefroi in French; Sigfrid in Luxembourgish) bought the feudal rights to the territory on which he founded his capital city of Luxembourg, his name became connected with the local version of Melusine. This Melusina had essentially the same magic gifts as the ancestress of the Lusignans, magically making the Castle of Luxembourg on the Bock rock (the historical center point of Luxembourg City) appear the morning after their wedding. On her terms of marriage, she too required one day of absolute privacy each week.

Alas, Sigfrid, as the Luxem-bourgish call him, “could not resist temptation, and on one of the forbidden days he spied on her in her bath and discovered her to be a mermaid. When he let out a surprised cry, Melusina caught sight of him, and her bath immediately sank into the solid rock, carrying her with it. Melusina surfaces briefly every seven years as a beautiful woman or as a serpent, holding a small golden key in her mouth. Whoever takes the key from her will set her free and may claim her as his bride.” In 1997 Luxembourg issued a postage stamp commemorating her.[6]

Martin Luther knew and believed in the story of another version of Melusine, die Melusina zu Lucelberg (Lucelberg in Silesia), whom he referred to several times as a succubus (Works, Erlangen edition, volume 60, pp 37–42). Johann Wolfgang von Goethe wrote the tale of Die Neue Melusine in 1807 and published it as part of Wilhelm Meisters Wanderjahre. The playwright Franz Grillparzer brought Goethe’s tale to the stage and Felix Mendelssohn provided a concert overture “The Fair Melusina,” his Opus 32.

Melusine is one of the pre-Christian water-faeries[citation needed] who were sometimes responsible for changelings. The “Lady of the Lake“, who spirited away the infant Lancelot and raised the child, was such a water nymph. Other European water sprites include Lorelei and the nixie.

“Melusina” would seem to be an uneasy name for a girl-child in these areas of Europe, but Ehrengard Melusine von der Schulenburg, Duchess of Kendal and Munster, mistress of George I of Great Britain, was christened Melusine in 1667.

The chronicler Gerald of Wales reported that Richard I of England was fond of telling a tale according to which he was a descendant of a countess of Anjou who was in fact the fairy Melusine. [7] The Angevin legend told of an early Count of Anjou who met a beautiful woman when in a far land, where he married her. He had not troubled to find out about her origins. However, after bearing him four sons, the behavior of his wife began to trouble the count. She attended church infrequently, and always left before the Mass proper. One day he had four of his men forcibly restrain his wife as she rose to leave the church. Melusine evaded the men and clasped the two youngest of her sons and in full view of the congregation carried them up into the air and out of the church through its highest window. Melusine and her two sons were never seen again. One of the remaining sons was the ancestor, it was claimed, of the later Counts of Anjou and the Kings of England. [8]

Related legends

The Travels of Sir John Mandeville recounts a legend about Hippocrates‘ daughter. She was transformed into a hundred-foot-long dragon by the goddess Diane, and is the “lady of the manor” of an old castle. She emerges three times a year and will be turned back into a woman if a knight kisses her, making the knight into her consort and ruler of the islands. Various knights try, but flee when they see the hideous dragon; they die soon thereafter. This appears to be an early version of the legend of Melusine. [9]

Structural interpretation

Jacques Le Goff considered that Melusina represented a fertility figure: “she brings prosperity in a rural area…Melusina is the fairy of medieval economic growth”.[10]

References in the arts

| hideThis section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)This section appears to contain trivial, minor, or unrelated references to popular culture. (May 2017)This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

“Melusine” by Julius Hübner.

- Melusine is the subject of Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué‘s novella Undine (1811), Halévy‘s grand opera La magicienne (1858) and Jean Giraudoux‘s play Ondine (1939).

- Antonín Dvořák‘s Rusalka, Opera in three acts, Libretto by Jaroslav Kvapil, is also based on the fairy tale Undine by Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué.

- Felix Mendelssohn depicted the character in his concert overture The Fair Melusine (Zum Märchen von der Schönen Melusine), opus 32.

- Marcel Proust‘s main character compares Gilberte to Melusine in Within a Budding Grove. She is also compared on several occasions to the Duchesse de Guermantes who was (according to the Duc de Guermantes) directly descended from the Lusignan dynasty. In the Guermantes Way, for example, the narrator observes that the Lusignan family “was fated to become extinct on the day when the fairy Melusine should disappear” (Volume II, Page 5, Vintage Edition.).

- The story of Melusine (also called Melusina) was retold by Letitia Landon in the poem “The Fairy of the Fountains” in Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834,[11] and reprinted in her collection The Zenana. Here she is representative of the female poet. An analysis can be found in Anne DeLong, pages 124–131. [12]

- Mélusine appears as a minor character in James Branch Cabell‘s Domnei: A Comedy of Woman-Worship (1913 as The Soul of Melicent, rev. 1920) and The High Place (1923).

- In Our Lady of the Flowers, Jean Genet twice says that Divine, the main character, is descended from “the siren Melusina” (pp. 198, 298 of the Grove Press English edition (1994)). (The conceit may have been inspired by Genet’s reading of Proust.)

- Melusine appears to have inspired aspects of the character Mélisande, who is associated with springs and waters, in Maurice Maeterlinck‘s play Pelléas and Mélisande, first produced in 1893. Claude Debussy adapted it as an opera by the same name, produced in 1902.

- In Wilhelm Meister’s Journeyman Years, Goethe re-tells the Melusine tale in a short story titled “The New Melusine”.

- Georg Trakl wrote a poem titled “Melusine”.

- Margaret Irwin’s fantasy novel These Mortals (1925) revolves around Melusine leaving her father’s palace, and having adventures in the world of humans. [13]

- Charlotte Haldane wrote a study of Melusine in 1936 (which her then husband J.B.S. Haldane referred to in his children’s book “My Friend Mr Leakey”).

- Aribert Reimann composed an opera Melusine, which premiered in 1971.

- The Melusine legend is featured in A. S. Byatt‘s late 20th century novel Possession. One of the main characters, Christabel LaMotte, writes an epic poem about Melusina.

- Philip the Good‘s 1454 Feast of the Pheasant featured as one of the lavish ‘entremets’ (or table decorations) a mechanical depiction of Melusine as a dragon flying around the castle of Lusignan. [14]

- Rosemary Hawley Jarman used a reference from Sabine Baring-Gould‘s Curious Myths of the Middle Ages[15] that the House of Luxembourg claimed descent from Melusine in her 1972 novel The King’s Grey Mare, making Elizabeth Woodville‘s family claim descent from the water-spirit. [16] This element is repeated in Philippa Gregory‘s novels The White Queen (2009) and The Lady of the Rivers (2011), but with Jacquetta of Luxembourg telling Elizabeth that their descent from Melusine comes through the Dukes of Burgundy. [17][5]

- In his 2016 novel In Search of Sixpence the writer Michael Paraskos retells the story of Melusine by imagining her as a Turkish Cypriot girl forceably abducted from the island by a visiting Frenchman.

- Kurt Heasley of the US band Lilys wrote a song titled “Melusina” for the 2003 album Precollection.

- French singer Nolwenn Leroy recorded a song titled “Mélusine” on her album Histoires Naturelles in 2005.

- The gothic metal band Leaves’ Eyes released a song and EP titled “Melusine” in April 2011.

- In Final Fantasy V, a video game RPG originally released by Squaresoft for the Super Famicom in 1992, Melusine appears as a boss. Her name was mistranslated as “Mellusion” in the PS1 port included as part of Final Fantasy Anthology but was correctly translated in subsequent localizations.

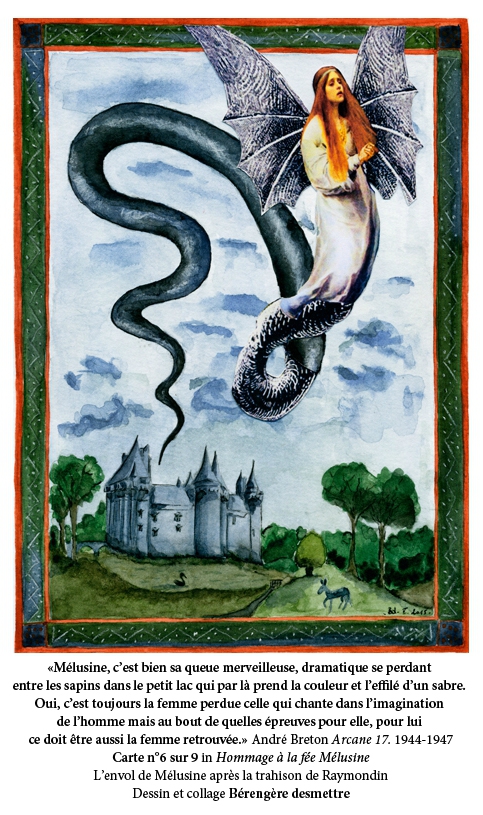

- The fairy is said to be “a recurring metaphor” in Breton’s Arcanum 17.

- In Czech and Slovak, the word meluzína refers to wailing wind, usually in the chimney. This is a reference to the wailing Melusine looking for her children. [18]

- In the video game The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, a particularly powerful siren is named Melusine.

- In the video game Final Fantasy XV, the sidequest “O Partner, My Partner” has the player pitted against a level 99 daemon named Melusine, she is depicted as a beautiful woman, wrapped in snakes. In this version she is weak to fire despite usually depicted as a being of water.

- In the movie Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald actress Olwen Fouéré plays a character named “Melusine”.

- In the book “Light and Shadow”, part 5 of The Longsword Chronicles by GJ Kelly, ‘The Melusine’ is the name of a coastal brigantine of the Royal Callodon Navy.

- The video game Sigi – A Fart for Melusina is a parody of the legend. The player character is Siegfried, who tries to rescue his beloved Melusine.

- In June 2019, it was announced that Luxembourg’s first petascale supercomputer, a part of the European High-Performance Computing Joint Undertaking (EuroHPC JU) programme, is to be named “Meluxina”. [19]

- The Starbucks logo is Melusine. [20]

- In the webcomic Eerie Cuties, one of the main characters is a melusine named Brook. She takes a human form with a snake around her neck most of the time, though changes into her snake form on occasion.

See also

- Echidna (mythology) Greek Mythological serpent woman, mother of monsters

- Legend of the White Snake

- Morgen (mythological creature)

- Neck (water spirit)

- Naiad

- Potamides (mythology)

- Partonopeus de Blois

- Yuki-onna

- Knight of the Swan

References

- Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox, Melusine of Lusignan: foundling fiction in late medieval France. Essays on the Roman de Mélusine (1393) of Jean d’Arras.

- Lydia Zeldenrust, The Mélusine Romance in Medieval Europe: Translation, Circulation, and Material Contexts. (Cambridge: D.S. Brewer, 2020) (on the many translations of the romance, covering French, German, Dutch, Castilian, and English versions) ISBN 9781843845218

- Jean d’Arras, Mélusine, roman du XIVe siècle, ed. Louis Stouff. Dijon: Bernigaud & Privat, 1932. (Scholarly edition of the important medieval French version of the legend by Jean d’Arras.)

- Otto j. Eckert, “Luther and the Reformation,” lecture, 1955. e-text

- Proust, Marcel. (C. K. Scott Moncrieff, trans.) Within A Budding Grove. (Page 190)

- ^ Baring-Gould, Sabine (1882). Curious Myths of the Middle Ages. Boston: Roberts Brothers. pp. 343–393.

- ^ Lydia Zeldenrust, The Mélusine Romance in Medieval Europe: Translation, Circulation, and Material Contexts (Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2020)

- ^ Boria Sax, The Serpent and the Swan: Animal Brides in Literature and Folklore. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press/ McDonald & Woodward, 1998.

- ^ Láinez, Manuel Mujica (1983) The Wandering Unicorn Chatto & Windus, London ISBN 0-7011-2686-8;

- ^ Jump up to:a b Philippa Gregory; David Baldwin; Michael Jones (2011). The Women of the Cousins’ War. London: Simon & Schuster.

- ^ Luxembourg Stamps: 1997

- ^ Flori, Jean (1999), Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier, Paris: Biographie Payot, ISBN 978-2-228-89272-8 (in French)

- ^ Huscroft, R. (2016) Tales From the Long Twelfth Century: The Rise and Fall of the Angevin Empire, Yale University Press, pp. xix–xx

- ^ Christiane Deluz, Le livre de Jehan de Mandeville, Leuven 1998, p. 215, as reported by Anthony Bale, trans., The Book of Marvels and Travels, Oxford 2012, ISBN 0199600600, p. 15and footnote

- ^ J. Le Goff, Time, Work and Culture in the Middle Ages (London 1982) p. 218-9

- ^ Letitia Landon

- ^ DeLong

- ^ Brian Stableford, ” Re-Enchantment in the Aftermath of War”, in Stableford, Gothic Grotesques: Essays on Fantastic Literature. Wildside Press, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4344-0339-1 (p.110-121)

- ^ Jeffrey Chipps Smith, The Artistic Patronage of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1419–1467), PhD thesis (Columbia University, 1979), p. 146

- ^ “Stephan, a Dominican, of the house of Lusignan, developed the work of Jean d’Arras, and made the story so famous, that the families of Luxembourg, Rohan, and Sassenage altered their pedigrees so as to be able to claim descent from the illustrious Melusina”, citing Jean-Baptiste Bullet‘s Dissertation sur la mythologie française (1771).

- ^ Jarman, Rosemary Hawley (1972). “Foreword”. The King’s Grey Mare.

- ^ Gregory, Philippa (2009). “Chapter One” (PDF). The White Queen.

- ^ Smith, G.S.; C. M. MacRobert; G. C. Stone (1996). Oxford Slavonic Papers, New Series. XXVIII (28, illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press, USA. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-19-815916-2.

- ^ “Le superordinateur luxembourgeois “Meluxina” fera partie du réseau européen EuroHPC” [Luxembourgish supercomputer “Meluxina” will be part of the EuroHPC European network]. gouvernement.lu (in French). 14 June 2019. Retrieved 30 June2019.

- ^ “So, Who is the Siren? | Starbucks Coffee Company”. web.archive.org. 2011-01-08. Retrieved 2021-03-10.

- Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Fisher’s Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1834.

- Anne DeLong. Mesmerism, Medusa and the Muse, The Romantic Discourse of Spontaneous Creativity, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Melusine. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:Curious Myths of the Middle Ages: Melusina |

- “Melusina”, translated legends about mermaids and water sprites that marry mortal men, with sources noted, edited by D. L. Ashliman, at University of Pittsburgh

- Terri Windling, “Married to Magic: Animal Brides and Bridegrooms in Folklore and Fantasy”

- Sir Walter Scott, Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (e-text)

- Jean D’Arras, Melusine, Archive.org

- “Mélusine” . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

| Authority control | BNF: cb11949589t (data)GND: 118580590NKC: jo20201089147SUDOC: 02745973XVIAF: 205817288WorldCat Identities: viaf-205817288 |

|---|

- European legendary creatures

- Fictional Scottish people

- Medieval legends

- French legendary creatures

- European dragons

- Mythological human hybrids

- Water spirits

- Mermaids

‘Melusine came to Lusignan and circled it three times, shrieking woefully in a plaintive female voice. Up in the fortress and in the town below, people were utterly amazed; they knew not what to think, for they could see the form of a serpent, yet they heard the lady’s voice issuing forth from it’.

Jean d’Arras, Roman de Mélusine (1393), M 260-261.[1]

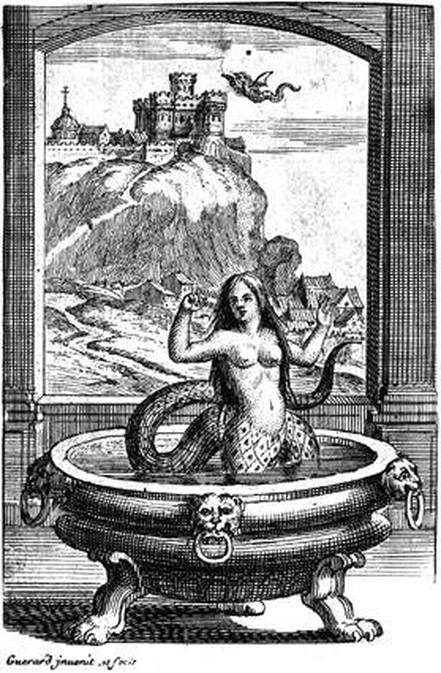

Image of Melusine as a mermaid/serpent from Le Livre de Mélusine (Geneva, 1478).

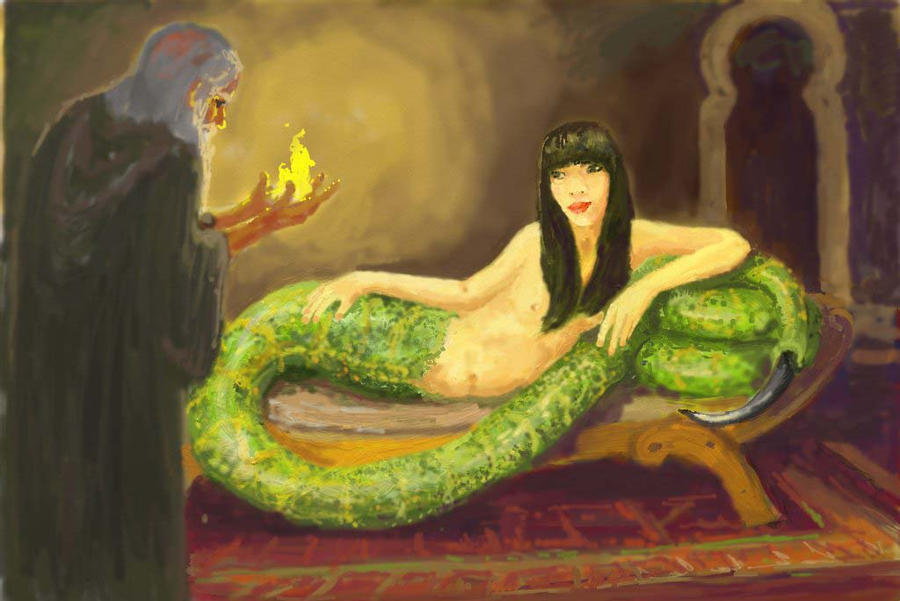

The story of the fairy Melusine dates from the late fourteenth-century, but has its origins in many human-hybrid folktales of the oral tradition.[2] Melusine, a daughter of a human father and a fairy mother, could be said to have started life as a hybrid and in the course of her mythical career exhibited a number of different hybrid forms. Having transgressed against her father, she was cursed by her mother, the fairy Presine, to turn into a serpent every Saturday. Her only hope of salvation was to find a man who would love her enough to a) respect her privacy every Saturday; and b) if he ever did find out that she was part serpent, to ignore this fact and keep her secret.

The story (or perhaps in Melusine’s case we should say the tale), tells us that Melusine met Count Raymondin, and the two fell in love. Together they had ten sons, eight of whom bore some mark of their fairy ancestry and many of whom proved to be fearsome warriors. Melusine and Raymondin remained very much in love until one day Raymondin’s cousin, the Count of Forez, counselled Raymondin to find out what his wife actually did on a Saturday. Could she be having an affair? Why was there such mystery? The doubts gnawed at Raymondin until eventually he decided to spy on her and, when he did, he realised that Melusine’s secret was that she was only part human. From the waist upwards she was a beautiful woman, but from the waist down, she was a serpent – as we see in this woodcut from one of the first printed versions of the story.

But what type of hybrid creature was she? As the images above and below demonstrate, categorizing Melusine proved difficult. In the 1478 woodcut of the French editio princeps she is very much like a mermaid, although her tail is that of a serpent, rather than a fish. Her chronicler Jean d’Arras tells us that when Raymondin saw Melusine in her bathtub ‘from her head to her navel she had the form of a woman and was combing her hair; and from her navel down she had the form of a serpent’s tail, as thick as a herring barrel, and very long, and she was splashing her tail in the water so much that she made it shoot up to the ceiling’.[3] In the image below, from a contemporary manuscript, we see that she is depicted with wings (an allusion to her final transformation into a dragon), for Melusine’s story did not end with the initial betrayal by Raymondin.[4]

Image of Melusine as a serpent with wings from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, fifteenth-century manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

As Jean d’Arras’ Mélusine ou La Noble Histoire de Lusignan, written c. 1393 relates, Melusine decided to forgive Raymondin’s initial transgression. However, following the murder of one of their sons by another, Raymondin publicly denounced his wife, blaming her for her son’s murderous/monstrous nature. It was at this point that the curse came into effect because Raymondin had publicly repudiated her. As her mother Presine had foretold, Melusine was now condemned to become wholly serpent and had lost all hope of becoming human:

If you had not been false I would have been spared pain and torment, and I would have lived like a natural [human] woman, and I would have died a natural death, with all my sacraments, and I would have been buried in the church of Notre Dame de Lusignan, and my day would have been celebrated. But you have inflicted upon me an obscure penance that stems from my past misfortunes. And for this reason, I must suffer until the Day of Judgment because of your falseness. I pray God may forgive you. [5]

©Photo. R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojda

Image of Melusine as a dragon, flying over the Château de Lusignan, from Les Très Riches Heures de duc de Berry, fifteenth-century manuscript in Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

As this image of Melusine, now depicted as a dragon, demonstrates, her fate was to fly away from Lusignan, only to return to foretell, with dire screams, the death of each count. So in one version of the story, a hybrid human-fairy creature became a hybrid human-serpent, who eventually becomes wholly serpent/dragon-like. Or did she? If we look at some of the printed woodcuts of the late fifteenth century, Melusine does indeed fly out of the top-most tower of Lusignan but does so in another hybrid body not unlike the second image here (i.e. she retains some evidence of her human form). [6]

The image of Melusine as a dragon flying over the castle of Lusignan is a vignette in the calendar page for March in the beautiful manuscript known as the Les Très Riches Heures de duc de Berry. This manuscript was commissioned by and was one of the treasured possessions of Jean (1340-1416), Duc de Berry, third son of Jean II of France and Bonne of Luxembourg. Jean d’Arras’ 1393 tale of the fairy Melusine was not just written to entertain his audience: he had been specifically commissioned by Jean, Duc de Berry to write the story as part of a propaganda campaign for his patron, the new Lord of Lusignan.

The end of the story relates that Melusine came back one last time to Lusignan, just before Jean, Duc de Berry’s forces raised the siege of the castle in 1374. In this way, Melusine, the legendary builder of the castle, could be viewed as noting the passage of the fortress into new hands. Her presence was to mark the ending of English power there and the beginning of Jean, Duc de Berry’s reign as Lord of Lusignan. In effect, by using the story in this fashion, the new Lord of Lusignan was seeking to bolster his credentials as the true Lord of Lusignan, whose coming had been foretold by its foundress.[7]

Given Jean Duc de Berry’s interest in the appropriation of the Melusine myth for his own political ends, the unusually favourable treatment of Melusine in Jean d’Arras narrative begins to make sense, for though her sons have monstrous attributes, she herself, though she transforms into a serpent, is still considered to be a good and true lady. Melusine’s essentially good nature is emphasised throughout Jean d’Arras’s tale: when she first meets Raymondin at the fountain, she makes it clear that her powers might seem like the work of the devil but that she herself was ‘on God’s side and …

I believe everything a true Christian must believe’.[8] Even more strikingly, when she finally transforms into a dragon, we are told that the people of the city, ‘cried out with one voice: Today we are losing the most valiant lady, who ever governed a land, and the wisest, the humblest, the most charitable, the best loved and most attentive to the needs of her people, who has ever been seen’.[9] Melusine’s orthodoxy is further emphasised in the advice she gives her two youngest sons before she departs forever: ‘Listen to what I say and keep it always in mind, because it is important.

First, love and serve God, your Creator, always. Obey all the commandments of our holy Church and all the teachings and commandments of our Catholic faith’.[10] If Jean, Duc de Berry, was claiming a link with a dragon foundress, at least the dragon was a true Christian! The villain of the piece (or perhaps misguided idiot would be closer), is not Melusine in her final, dragon-like, incarnation but rather her husband who, although he will suffer their separation, will not have to endure being a serpent for all eternity.

Image of Melusine on the binding of a book owned by Louis-Henri de Lomenie, Comte de Brienne: Worth’s copy of Ulisse Aldrovandi, Serpentum, et draconum historiæ libri duo (Bologna, 1640), front cover details.

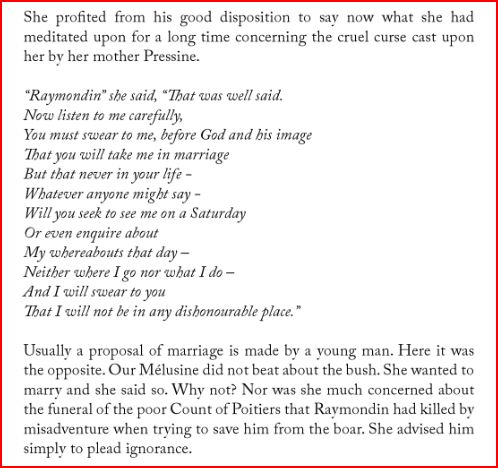

Jean, Duc de Berry, wasn’t the only one who sought to appropriate the allure of Melusine in an attempt to raise his own political fortunes. None of the manuscripts above are in the Worth Library but there is a connection between the legend of Melusine and Edward Worth for the latter’s library includes a number of bindings on books belonging to Louis-Henri Lomenie (1635-1698), Comte de Brienne. As this image demonstrates, Melusine was, quite literally, the crowning glory in Louis-Henri’s coat of arms. Here we see her in yet another guise – in a washtub, holding up a mirror and combing her hair (an allusion to Melusine in mermaid form).

Why did Louis-Henri Lomenie, Comte de Brienne, a noble man in seventeenth-century France, decide to include this reference to the fairy Melusine in his family coat of arms? The answer lies in a desire for power. The famous and powerful Lusignan family were said to have been from the Limoisin, the same area from which the new comtes de Brienne claimed descent. In addition, Louis-Henri probably had in mind the claim that the comtes de Luxembourg were likewise descendants of Melusine since his mother was of the House of Luxembourg: Louise de Béon-Luxembourg (d. 1665), was one of the descendants of Charles, the twenty-fifth comte de Brienne, and was, in addition, an heiress of the House of Luxembourg.]

The two cows, seen here in the 1st and 4th quarter of the coat of arms, represent the House of Béon, while the rampant crowned lions represent the House of Luxembourg. By including the Luxembourg elements on his coat of arms, and, in addition, adding the mysterious fairy Melusine, Lomenie de Brienne sought to move up the slippery ladder of power at the French court. For Louis-Henri it was simply too good a story to ignore and the fair Melusine graces many of the bindings on his books in the Worth Library.

As Ridley Elmes reminds us, Jean, Duc de Berry, and Louis-Henri Lomenie, Comte de Brienne, may have appropriated the legend of Melusine for political ends but her story might also be interpreted in other ways.[12] The sixteenth-century doctor, Paracelsus (1493-1641), wrote about Melusine as type, rather than Melusine as ancestral progenitrix. His treatise On Nymphs, Sylphs, Pygmies and Salamanders, includes a section on water nymphs of which Melusine is one of the most famous examples. Like Jean d’Arras, he emphasised Melusine’s quest to become human. At the same time, Melusine, for Paracelsus, was less an ancestral figure and more an alchemical principle, one which played a vital role in the union of Iliaster and Aquaster into the Primordial Man.[13]

One might conclude that Melusine’s multiple forms reflect the multitude of meanings ascribed to her. That her legend lives on may be seen in the decision of the city of Luxembourg to erect a statue in her honour to mark the 1050th anniversary of the city’s foundation in 2015. Here too, we see another variation on the tale: for Melusina of Luxembourg is shown as a mermaid.

Sources

Brownlee, Kevin, ‘Melusine’s Hybrid Body and the Poetics of Metamorphosis’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), pp 76-99.

Brownlee, Marina S., ‘Interference in Mélusine,’ in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan: Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), pp 226-240.

Chambers, Jane, ‘“For Love’s Sake”: Lamia and Burton’s Love Melancholy’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 22, no. 4 (1982), 583-600.

Delogu, Daisy, ‘Jean d’Arras Makes History: Political Legitimacy and the Roman de Mélusine’, Dalhousie French Studies, 80 (Fall 2007), 15-28.

Maddox, Donald, and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan: Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996).

Guigard, Joannis, Nouvel Armorial du Bibliophile : Guide de l’Amateur des livres armoriés (Paris: Rondeau, 1890), 2 vols.

Péporté, Pit, ‘Melusine and Luxembourg: A Double Memory’, in Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis and Melissa Ridley Elmes (eds), Melusine’s Footprint: Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth (Leiden, 2017), pp 162-182.

Ridley Elmes, Melissa, ‘The Alchemical Transformation of Melusine’, in Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis and Melissa Ridley Elmes (eds), Melusine’s Footprint: Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth (Leiden, 2017), pp 94-108.

Nichols, Stephen G., ‘Melusine between Myth and History: Profile of a Female Demon’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan: Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), pp 137-164.

Sturm Maddox, Sara, ‘Crossed Destinies: Narrative Programs’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan: Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), pp 12-31.

Urban, Misty, Deva F. Kemmis and Melissa Ridley Elmes (eds), Melusine’s Footprint: Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth (Leiden, 2017).

Zeldenrust, Lydia, ‘Serpent or Half-Serpent? Bernhard Richel’s Melusine and the Making of a Western European Icon’, Neophilologus, 100 (2016), 19-41.

Text: Dr. Elizabethanne Boran, Librarian of the Edward Worth Library.

[1] Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox, ‘Introduction: Melusine at 600’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), p. 1.

[2] Chambers notes an ancient Greek story with similarities to the story of Melusine: Jane Chambers, ‘“For Love’s Sake”: Lamia and Burton’s Love Melancholy’, Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, 22: 4 (1982), 583-600.

[3] Kevin Brownlee, ‘Melusine’s Hybrid Body and the Poetics of Metamorphosis’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), p. 80.

[4] Nichols notes that this latter visual image of Melusine links her iconographically with the theme of the ‘winged siren’: Stephen G. Nichols, ‘Melusine between Myth and History: Profile of a Female Demon’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), p. 139.

[5] Marina S. Brownlee, ‘Interference in Mélusine’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), p. 234.

[6] On this see Lydia Zeldenrust, ‘Serpent or Half-Serpent? Bernhard Richel’s Melusine and the Making of a Western European Icon’, Neophilologus, 100 (2016), 19-41.

[7] On this point see Pit Péporté, ‘Melusine and Luxembourg: A Double Memory’, in Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis and Melissa Ridley Elmes (eds), Melusine’s Footprint. Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth (Leiden, 2017), pp 162-182 and Daisy Delogu, ‘Jean d’Arras Makes History: Political Legitimacy and the Roman de Mélusine’, Dalhousie French Studies, 80 (Fall 2007), 15-28.

[8] Sara Sturm Maddox, ‘Crossed Destinies’, p. 23.

[9] Sara Sturm Maddox, ‘Crossed Destinies: Narrative Programs’, in Donald Maddox and Sara Sturm-Maddox (eds), Melusine of Lusignan. Founding Fiction in Late Medieval France (Athens, Georgia, 1996), p. 24.

[10] Brownlee, ‘Interference in Mélusine, p. 234.

[11] According to Guigard, her father was Bernard de Béon du Masseu and her mother was Louise de Luxembourg-Brienne: Joannis Guigard, Nouvel Armorial du Bibliophile. Guide de l’Amateur des livres armoriés (Paris: Rondeau, 1890), 2 vols, vol. II, p. 327.

[12] Melissa Ridley Elmes, ‘The Alchemical Transformation of Melusine’, in Misty Urban, Deva F. Kemmis and Melissa Ridley Elmes (eds), Melusine’s Footprint. Tracing the Legacy of a Medieval Myth (Leiden, 2017), pp 94-105.

[13] Ibid., p. 99, fn 20.

Melusine’s Possible Lusignan, Luxembourg, and Plantagenet Descendants

From: https://childrenofarthur.wordpress.com/tag/melusine-of-lusignan/

I have long been interested in the Fairy Melusine, as evidenced by my writing the book Melusine’s Gift. While researching that novel, I learned that Melusine was referenced in Philippa Gregory’s The Cousins War series, beginning with The Lady of the Rivers, so I had to read those novels. I found them fascinating since I’ve also long been interested in the Wars of the Roses. Indeed, it’s possible that I am descended from Elizabeth Woodville, and her mother, Jacquetta of Luxembourg, who figure prominently in the novels.

Melusine

But one thing confused me about Gregory’s depiction of Melusine. Her insistence that Jacquetta, and the House of Luxembourg, was descended from the famous mermaid-like fairy. I assumed there must be some source to this idea, but Gregory never explains the connection in the novel. Melusine is better known as the ancestor to the House of Lusignan, so I could only guess that some member of the House of Lusignan had married into the House of Luxembourg, but who?

I also was surprised by Gregory making the English characters in the novel suspicious of Jacquetta and Elizabeth because of their connection to Melusine. Both women are even accused of witchcraft, so clearly descent from a famous mythical creature—sorceress, mermaid, flying serpent woman, however you want to describe Melusine—was a partial explanation for this fear and their belief that the women might share their ancestor’s supernatural powers. But Gregory completely ignored that the English royal family, the Plantagenets, including Edward IV, whom Elizabeth Woodville married, themselves claimed descent from Melusine. Not until the final novel in the series, The King’s Curse, does she even make a passing reference to this connection.

Where did Gregory get the idea that the House of Luxembourg could be descended from Melusine? According to Wikipedia, Gregory may have gotten this idea from another novelist. “Rosemary Hawley Jarman used a reference from Sabine Baring-Gould’s Curious Myths of the Middle Ages that the House of Luxembourg claimed descent from Melusine in her 1972 novel The King’s Grey Mare, making Elizabeth Woodville’s family claim descent from the water-spirit. This element is repeated in Philippa Gregory’s novels The White Queen (2009) and The Lady of the Rivers (2011), but with Jacquetta of Luxembourg telling Elizabeth that their descent from Melusine comes through the Dukes of Burgundy.”

First, let me say that the claim of the Dukes of Burgundy to being descended from Melusine seems unlikely. In fact, I believe Gregory made up the connection that the House of Luxembourg is connected to the House of Burgundy. If they were at the time of the mid-fifteenth century, it was a very tenuous connection and I could not find a connection. Furthermore, the Dukes of Burgundy during Jacquetta’s time in the early fifteenth century were directly descended from the French royal family.

Baring-Gould’s claim that the House of Luxembourg claimed descent from Melusine is true, but it is not a credible claim. In fact, in The Book of Melusine of Lusignan by Gareth Knight, who is perhaps the greatest expert on Melusine, it is stated that the Luxembourg legend says that Sigefroy, first Count of Lusignan, married a woman named Melusine (p. 117). Since we know Melusine married Count Raimond of Lusignan in other versions of the legend, it is likely various nobles just decided to make up their own connections to Melusine. Somehow, I just don’t see Melusine as a bigamist who deserted Raimond and then went and remarried. Furthermore, Sigefroy is considered the first count of Luxembourg and he lived in the tenth century, while Melusine seems to have lived in the eighth century when she is married to Raimond of Lusignan. Plus, we know that Sigefroy was married to Hedwig of Nordgau, by whom he had several children, including those through whom the House of Luxembourg descended.

So the link between Melusine and Luxembourg seems to be completely fanciful, but still, I decided to dig into Jacquetta’s family tree to see whether I could find any Lusignan link, and believe it or not, I did find a connection. The link is actually through Jacquetta’s paternal grandmother’s line, as shown below. The tree begins with the first documented member of the House of Lusignan, Hugh I, who lived in the ninth century and whom we can presume would be the alleged descendant of Melusine. Each person on the chart is the parent of the person below him or her.

Lusignan Genealogy, linking to Luxembourg

Hugh I

Hugh II (d. 967) According to the Chronicle of Saint-Maixent, he built the castle at Lusignan.

Hugh III

Hugh IV (d.1026)

Hugh V (d.1060)

Hugh VI (1039/43-1103/10)

Hugh VII of Lusignan (1065-1171)

Hugh VIII of Lusignan (d. 1165/71)

Aimery of Lusignan (1145-1205) – brother to Guy, King of Jerusalem

Hugh I of Cyprus (1194/5-1218)

Marie de Lusignan (1215-1251/3)

Hugh, Count of Brienne (1240-1296)

Walter V of Brienne (1278-1311)

Isabella of Brienne (1306-1360), claimant to the Kingdom of Jerusalem

Louis of Enghien (d. 1394)

Marguerite of Enghien (b. 1365) m. John of Luxembourg, Lord of Beauvoir

Peter of Luxembourg, Count of Saint-Pol (1390-1433)

Jacquetta of Luxembourg married Earl Rivers

Elizabeth, Queen of England m. Edward IV

Elizabeth of York m. Henry VII

Henry VIII of England

The genealogy above is a very roundabout way to connect Luxembourg to Lusignan, but the connection is there. That said, Jacquetta was as closely connected to the Plantagenets already as she was to Lusignan, being a descendant of Plantagenet king Henry III as shown below.

Henry III of England (1208-1272)

Beatrice of England (1242-1275) m. John II, Duke of Brittany

Marie of Brittany (1268-1339)

John of Chatillon, Count of Saint-Pol (d. 1344)

Mahaut of Chatillon, Countess of Saint-Pol

John of Luxembourgh, Lord of Beauvoir

Peter of Luxembourg

Jacquetta of Luxembourg

This chart would mean that Jacquetta would also be potentially descended from Melusine if it were true that the Plantagenets were descended from Melusine. But what was the Plantagenet connection? We know that Richard the Lionhearted, who was brother to King John and, therefore, uncle to Henry III, used to like to joke about being descended from Melusine. Therefore, the link has to date to before the thirteenth century. The connection of the Plantagenets to the Lusignan’s actually exists in the line of Anjou from which the Plantagenet line descended.

about:

Fulk Anjou, King of Jerusalem

Geoffrey V of Anjou m. Maud, daughter of Henry I of England

Henry II of England

John of England

Henry III

Here’s where things get confusing. In the first chart above showing Jacquetta’s ancestors, we have Aimery of Lusignan, brother to King Guy of Jerusalem. The genealogy of the Kings of Jerusalem is full of marriages where husbands inherited the crown from their wives. Let’s try to unravel the genealogy of the Kings of Jerusalem.

Fulk of Anjou, King of Jerusalem m. Ermengarde of Maine. They were the parents of Geoffrey of Anjou, progenitor of the Plantagenets. Fulk later married Melisende, Queen of Jerusalem. They had two sons Baldwin III and Amalric, both Kings of Jerusalem. Melisende was herself the daughter of King Baldwin II of Jerusalem, so Fulk achieved the throne through marriage. Also, notably, Melisende is often confused with Melusine because of the similar name, though that may or may not be the cause of the Plantagenet claim to descent from Melusine.

Melisende got her own name from her father, King Baldwin II’s mother, Melisende, who was the daughter of Guy I of Montlhery. Who Guy’s father was is questionable. According to Wikipedia, he was probably the third son of Thibault of Montlhery, though some sources say his father’s name was Milo. I find this latter assertion interesting since the Fairy Melusine may have had a son named Milo or Milon according to some less than creditable sources. But that does not explain the link between Lusignan and the Plantagenets.

As it turns out, Fulk’s son, Amalric, had a daughter, Sybilla, who ended up inheriting the crown of Jerusalem and passing it to her husband, Guy of Lusignan. The result is that the link between Plantagenets and Lusignan is only through marriage, making them sort of half-cousins, but the Plantagenets themselves are not direct descendants of Lusignan. At least not through the House of Anjou.

But a later Plantagenet link does exist. Henry III’s mother was Isabella of Angouleme. Isabella was engaged to marry Hugh IX of Lusignan (brother of Aimery and Guy) when King John instead married her and made her Queen of England. As a result, the Lusignans rebelled against the English king. After John’s death in 1216, Isabella returned to France and married in 1220 Hugh X, the son of her former fiancée. (Not so strange since he was within a few years of her age while King John was twenty-four years older than Isabella.) Hugh X and Isabella had many children who would have been the half-siblings to King Henry III. Among those children was Aymer, who became Bishop of Winchester, and Alice, who married the Earl of Surrey, while the other children seem to have remained in France. So again, another Lusignan connection for the Plantagenets, but again, only by marriage.

“The Wandering Unicorn” by Manuel Mujica Lainez is a fanciful novel about Melusine watching over her Lusignan descendants during the Crusades.

In any case, what is clear from these genealogical explorations is that if Melusine was the progenitor of the House of Lusignan, she had many, many descendants. But the question remains whether she even lived. The line of Lusignan can only be traced back for certain to Hugh I who lived in the early tenth century, and his son is likely the true builder of the Castle of Lusignan, which is reputed to have been built by Melusine. Searches for Hugh’s ancestry would be difficult and would require going back a century or two to find the ancestress Melusine if she existed at all. However, no records seem to exist of Hugh’s ancestry.

The question also arises whether we even know Melusine’s real name? According to The Serpent and the Swan: The Animal Bride in Folklore and Literature, the name Melusine was used by the first chroniclers of her tale, D’Arras and Couldrette, as an abbreviation of the French words “Mere des Lusignan” which would be “Mother of the Lusignans” in English (Source http://jungiangenealogy.weebly.com/melusine-de-alba.html). In other words, the real Melusine, like so many medieval and ancient women, remains nameless to us.

https://c0.pubmine.com/sf/0.0.3/html/safeframe.htmlREPORT THIS AD

______________________________________________________________________

Tyler Tichelaar, Ph.D., is the author of The Children of Arthur series, including the novels Arthur’s Legacy and Melusine’s Gift. You can learn more about him at www.ChildrenofArthur.com.

Melusine; the legend of the Lusignan Feudal Dynasty

“How the noble and powerful fortress of Lusignan of Poitou was founded by a fairy.”—Jean d’Arras, c.1500’s

Melusine by Jules Hubner

The legend of Melusine is the tale recorded by the poet Jean d’Arras, written about 1382 – 1394. It is considered one of the most complex and significant works of the late medieval ages. It was translated into English about the year 1500 and printed throughout the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It tells the tale, part historical, part myth, part legend, of the Lusignans, a Feudal Dynasty hailing from southwestern France and the region of Poitou. I learned of Melusine from my Parisian friend Robert Couturier while sharing the list of French castles that I hope to one day visit. The castle, La Rochefoucauld, lovely and unpretentious, sits at the top of my list. A sixteenth century staircase attributed to Leonardo da Vinci rests within. I’d like to climb those one hundred and eight steps. François de la Rochefoucauld was an author noted for his seventeenth century maxims and memoirs. He was considered the exemplar of the seventeenth century nobleman. He is known for writing aphorisms. An aphorism delivers a punch in three seconds. Think of it this way: aphorism= “We/one” + “subject that converts” + “makes us sting or laugh.”

“True love is like ghosts, which everybody talks about and few have seen.”

“We forgive so long as we love.”

“To say one never flirts is in itself a form of flirtation.”

“We all have strength enough to bear the misfortunes of others.”

—François de la Rochefoucauld, Reflections or Sentences and Moral Maxims.

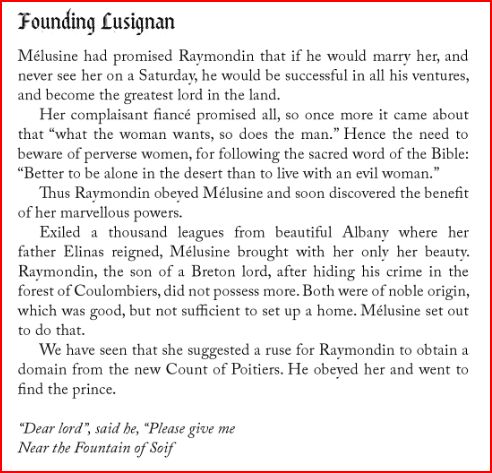

Robert knows the La Rochefoucauld family and shared the tale of one of the ten greatest historical families of France. The first was Foucauld de la Roche, son of Comte de Lusignan. The Lusignans ruled as kings of Jerusalem in the 12th century. Legend says that Melusine is their ancestress, and so the legend begins.

I have just placed in my basket at Amazon a copy of the 2012 release of Jean d’Arras’s, MELUSINE or, THE NOBLE HISTORY OF LUSIGNAN. When it arrives I will review his work and embellish this post.

Melusine by Ludwig Michael von Schwanthaler, 1845

Her legend is shared with French school children early on by story or song. The tale is purported to be of Breton origin and equally hails from Poitou. There it is said she reigned as the fairy Queen of the forest of Colombiers. Her father was Elainas (Elynas) the King of Albany (Scotland), her mother the fairy Pressine.

One day while King Elainas was out hunting he stopped to quench his thirst at a spring, whereby he heard the voice of a woman singing. Here he met the fairy Pressine, though he questioned her he could not learn from where she came. They were married with the one condition that Elainas promise to never interrupt her while she was lying-in. Pressine gave birth to triplets, three daughters; Melusine, Meliot, and Palatine. Upon hearing the news that Pressine had given birth, Elainas could not contain his joy and burst in upon her while she was bathing her daughters. Pressine flew into a wrath of anger and promised that from then on her descendants would avenge her. She left with her daughters for the home of her sister the Queen of the Lost Island. (There is some reference made that this is Avalon…).

Illustration from Le Livre de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, 1478.

The Island of The Lost exists in the same way as all elusive mythical lands do, one finds it only by good fortune, luck or happenstance, stepping in only if the conditions are just right. Even those who seek for it will seek to no avail. That’s the important thing to remember. Pressine raised her daughters here high on a mountain-top from whereby they could see the land of Albany that of their father. As her daughters grew Pressine told them the story of why they were estranged from him. Melusine took it upon herself to devise the plot which unfolded with the aid of her two sisters. They traveled to Albany and using their feminine wiles tricked their father, along with his wealth, into seclusion and entrapment deep within the forest of Brandebois.

Pressine upon hearing the news flew into another of her—shall I say noteworthy— rages, and cast punishment in the direction of her three lovely daughters. Meliot was banished to an Armenian castle where she was locked away. Palatine was abandoned in the depths of the forest Brandebois with her father. Melusine was dealt the harshest punishment as she had plotted the mischief. Every Saturday Melusine turned into a ‘sea serpent’ from the waist down, does this mean she is the original mermaid? Her fate was to remain this way until the day she met a man willing to marry her on the condition that he never visited her on Saturday. (No, to the Saturday Night Date…)

Melusine set off to travel the world, passing through the Black Forest, followed by the Ardennes, she arrived finally in the forest of Colombiers, in Poitou. Here the inhabitants greeted her and said, “We have been waiting for you to rule the land.” One day Melsuine was guarding the Fountain of Thirst, or the Fountain of the Fays, at Colombiers with two friends, when Raimond de Lusignan stopped by. It was a fountain called thus because of the marvelous things that happened at the fountain which rose at the foot of a high rock. The two talked the night away and by morning agreed to be married on the one condition—as there are always conditions attached to relationships between mortals and fays—that they respect the Saturday night oath. Raimond was wandering in the forest after accidentally killing his uncle the Count of Poitou, (Guy de Lusignan, I believe but have to research and confirm), his arrow had deflected and struck the count while on a boar hunt. (This reminds me of a scene from the medieval comic film by Jean-Marie Poiré Just Visiting).

If Raimond were to forget his pledge and brake the vow, he’d lose her love forever more. The “happy wife, happy life” dictum is a forever refrain. They married and with the great wealth inherited from her father King Elainas, she built the castle Lusignan at the foot of the fountain where they’d first met. Melusine gave birth to ten boys, all of which had strange defects. One son had one blue eye and one red eye, one had a giant tooth… Despite their flaws, the children of Melusine and Raimond were loved throughout the land. Raimond’s love continued unabated, until the one, better forgotten day, when his curiosity could not be contained. Raimond had noticed that Melusine’s absences coincided with the building of a castle, church, monastery, town or tower—all of which happened over the course of one night as if by magic.One day Raimond’s brother was visiting and rallied by the enigmatic curiosity inherent in the marriage of his brother to Melusine, he persuaded—as we all know families have persuasive powers over us that we would often like to ignore, be it the thirteenth century or present moment—Raimond to sleuth out what she did each Saturday night.

Raimond spied her at her bath and was shocked. He discovered that from the waist down she was a serpent. He said nothing until the day that their son Geoffrey of the Giant Tooth went berserk and attacked a monastery killing one hundred monks, included in that count was one of his own brothers. Mon dieu. Raimond accused Melusine of ruining his lineage. Melusine took the form of a fifteen-foot serpent and flew from the castle circling it three times. Wailing her sorrows, returning to visit her children at night. Legend has it Raimond was never happy again, and that Melusine cries beside each Lusignan before their death and at their birth.

Alternate legend says that Melusine sank into a rock after Raimond spied her, where she is locked until every seventh year when she is freed and surfaces holding a golden key in her mouth. Whoever takes the key may claim her as his bride. (Sword in the stone sexism!) And did you notice the number seven?

Illustration from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, ca. 1450-1500.

The children of Melusine went on to become the King of Cyprus, the King of Armenia, the King of Bohemia, the Duke of Luxembourg, the last King of Jerusalem, and The Lord of Lusignan. It is said that her noble line will reign till the end of the world. Power to myth and legend.

“Myth equals an old, old story.”—Puccini

https://www.sunypress.edu/pdf/60616.pdf

In 719 Charles Martel defeated Rainfroi de VER, Duke of Anjou and Mayor of the Palace of Neustrie. This victory brought back together key houses of the Franks under one rule and is considered an important date in European history. Rainfroi de VER (also known as Raymond) was married to another legendary character, Melusine. Melusine de VER has also been known as Melusina, Melouziana de Scythes, Maelasanu, and The Dragon Princess. She entered literary history in the book Roman de Melusine written in 1393 by Jean d’Arras. The story is a mix of fiction and fact, commissioned by the Duke de Berry, a French noble who was brother to King Charles V, and uncle of King Charles VI. It was meant to be a family history and to uphold the proprietary claims to Lusignan and Anjou.

In this story, Melusine’s mother was a Presine fairy who charmed Elinas, the king of Scotland. The result was their daughter Melusine. Half fairy and half princess, Melusine wandered over to the Continent and eventually met up with Rainfroi/Raymond in the forests Anjou. They met while he was out boar hunting. Overcome with her beauty, he took her hand in marriage, and many adventures ensued. As a result of this book, Melusine was subsequently featured in medieval tales across Europe, variously depicted as a mermaid, a water sprite, a fairy queen, a fairy princess, a dragon princess, and a forest nymph.

She came to represent any magical creature who marries a mortal man. Most royal houses in Europe have claimed lineage to the real Melusine, so she has been the subject of great speculation. Legends about Melusine and Rainfroi (or Raymond) also often have a connection to boars and boar hunting. Charles Martel went on to become Duke of all the Franks and founder of the Carolinian line of Kings. Thirteen years later in 732 he defeated the Saracen Army at Poitiers in France and saved Western Europe from complete invasion by the Moslems.

As a result of this, his son Pepin III became 1st King of the Franks. Pepin in turn was the father of Charlemagne and Berta. Charlemagne, the 2nd King of the Franks, is the ancestor of every existing and former ruling house or dynasty in Europe. His sister Berta was joined in marriage to the son of Rainfroi de VER, Milo de VER in 800 AD, the same year her brother was crowned Holy Roman Emperor.

Milo de Ver was the Duke of Anjou, Count of Angleria, and Duke Leader of Charlemagne’s house. Milo and Berta had two sons, one being Roland (legendary Paladin for whom “Song of Roland” was written) and Milo de VER II. The de Ver line passed from Milo II through a succession of Earls of Genney: Milo II’s son Nicasius de VER was father to Otho de VER, father to Amelius de VER, father to Gallus de VER, father to Mansses de VER, father to Alphonso de VERE (Alphonsus). Alphonsus de VERE, Earl of Genney, was “Councilor to Edward the Confessor” King Edward III of England, who had both Norman and Flemish advisors. Alphonsus de VERE had a son Alberic de VERE, also known as Aubrey I.

NOTE: Aubrey comes from the Teutonic name Alberic, or “elf-ruler.”

992 Comments2 SharesLikeCommentShare

Melusine

‘Melusine came to Lusignan and circled it three times, shrieking woefully in a plaintive female voice. Up in the fortress and in the town below, people were utterly amazed; they knew not what to think, for they could see the form of a serpent, yet they heard the lady’s voice issuing forth from it’.

Jean d’Arras, Roman de Mélusine (1393), M 260-261.[1]

Image of Melusine as a mermaid/serpent from Le Livre de Mélusine (Geneva, 1478).

The story of the fairy Melusine dates from the late fourteenth-century, but has its origins in many human-hybrid folktales of the oral tradition.[2] Melusine, a daughter of a human father and a fairy mother, could be said to have started life as a hybrid and in the course of her mythical career exhibited a number of different hybrid forms. Having transgressed against her father, she was cursed by her mother, the fairy Presine, to turn into a serpent every Saturday. Her only hope of salvation was to find a man who would love her enough to a) respect her privacy every Saturday; and b) if he ever did find out that she was part serpent, to ignore this fact and keep her secret.

The story (or perhaps in Melusine’s case we should say the tale), tells us that Melusine met Count Raymondin, and the two fell in love. Together they had ten sons, eight of whom bore some mark of their fairy ancestry and many of whom proved to be fearsome warriors. Melusine and Raymondin remained very much in love until one day Raymondin’s cousin, the Count of Forez, counselled Raymondin to find out what his wife actually did on a Saturday. Could she be having an affair? Why was there such mystery? The doubts gnawed at Raymondin until eventually he decided to spy on her and, when he did, he realised that Melusine’s secret was that she was only part human. From the waist upwards she was a beautiful woman, but from the waist down, she was a serpent – as we see in this woodcut from one of the first printed versions of the story.

But what type of hybrid creature was she? As the images above and below demonstrate, categorizing Melusine proved difficult. In the 1478 woodcut of the French editio princeps she is very much like a mermaid, although her tail is that of a serpent, rather than a fish. Her chronicler Jean d’Arras tells us that when Raymondin saw Melusine in her bathtub ‘from her head to her navel she had the form of a woman and was combing her hair; and from her navel down she had the form of a serpent’s tail, as thick as a herring barrel, and very long, and she was splashing her tail in the water so much that she made it shoot up to the ceiling’.[3] In the image below, from a contemporary manuscript, we see that she is depicted with wings (an allusion to her final transformation into a dragon), for Melusine’s story did not end with the initial betrayal by Raymondin.[4]

Image of Melusine as a serpent with wings from Le Roman de Mélusine by Jean d’Arras, fifteenth-century manuscript, Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

As Jean d’Arras’ Mélusine ou La Noble Histoire de Lusignan, written c. 1393 relates, Melusine decided to forgive Raymondin’s initial transgression. However, following the murder of one of their sons by another, Raymondin publicly denounced his wife, blaming her for her son’s murderous/monstrous nature. It was at this point that the curse came into effect because Raymondin had publicly repudiated her. As her mother Presine had foretold, Melusine was now condemned to become wholly serpent and had lost all hope of becoming human:

If you had not been false I would have been spared pain and torment, and I would have lived like a natural [human] woman, and I would have died a natural death, with all my sacraments, and I would have been buried in the church of Notre Dame de Lusignan, and my day would have been celebrated. But you have inflicted upon me an obscure penance that stems from my past misfortunes. And for this reason I must suffer until the Day of Judgment because of your falseness. I pray God may forgive you.

©Photo. R.M.N. / R.-G. Ojda

Image of Melusine as a dragon, flying over the Château de Lusignan, from Les Très Riches Heures de duc de Berry, fifteenth-century manuscript in Musée Condé, Chantilly, France.

As this image of Melusine, now depicted as a dragon, demonstrates, her fate was to fly away from Lusignan, only to return to foretell, with dire screams, the death of each count. So in one version of the story a hybrid human-fairy creature became a hybrid human-serpent, who eventually becomes wholly serpent/dragon-like. Or did she? If we look at some of the printed woodcuts of the late fifteenth century, Melusine does indeed fly out of the top-most tower of Lusignan but does so in another hybrid body not unlike the second image here (i.e. she retains some evidence of her human form).[6]

The image of Melusine as a dragon flying over the castle of Lusignan is a vignette in the calendar page for March in the beautiful manuscript known as the Les Très Riches Heures de duc de Berry. This manuscript was commissioned by and was one of the treasured possessions of Jean (1340-1416), Duc de Berry, third son of Jean II of France and Bonne of Luxembourg. Jean d’Arras’ 1393 tale of the fairy Melusine was not just written to entertain his audience: he had been specifically commissioned by Jean, Duc de Berry to write the story as part of a propaganda campaign for his patron, the new Lord of Lusignan.